Gratiot County During Depression and War, March 1941: “Where is Spring?”

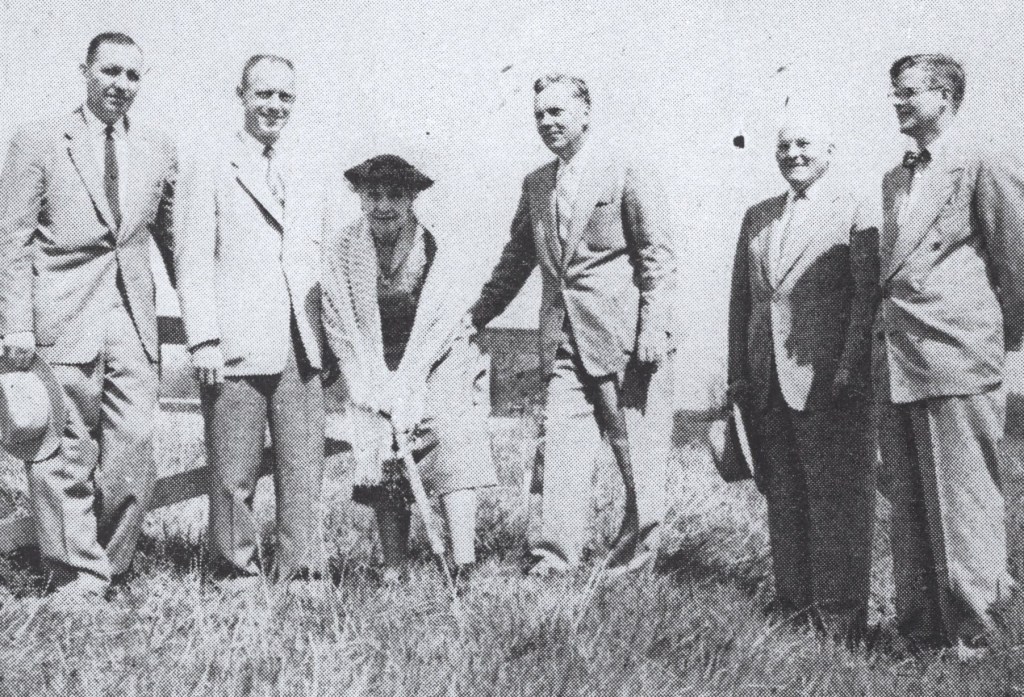

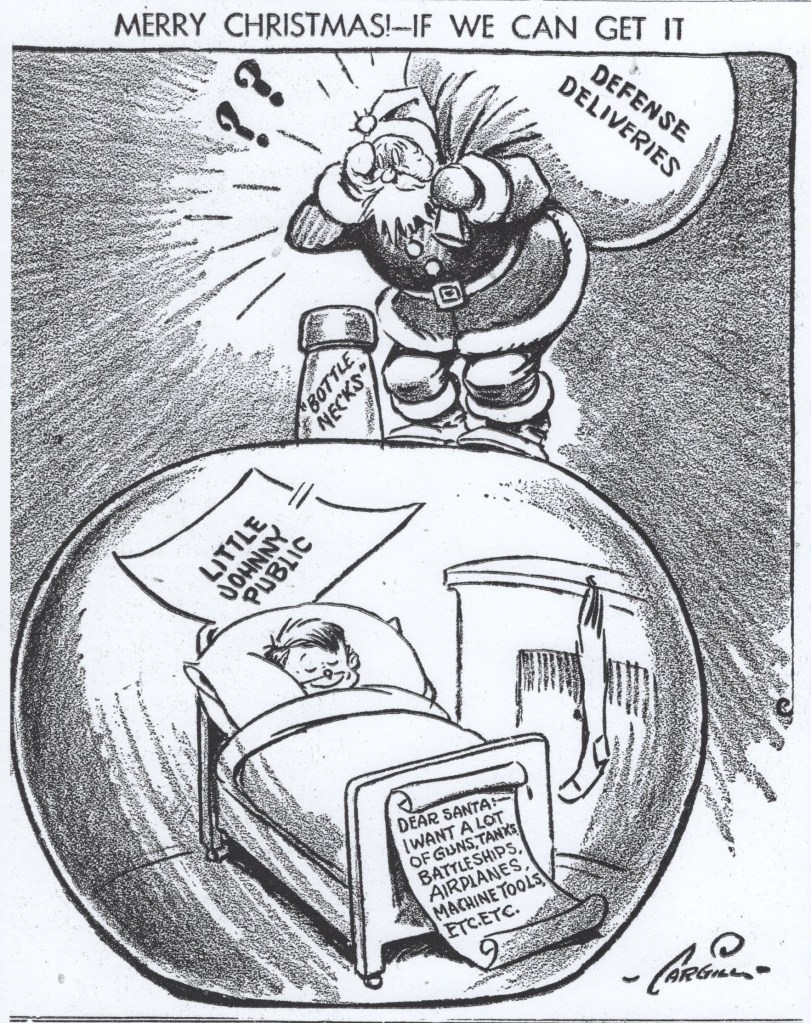

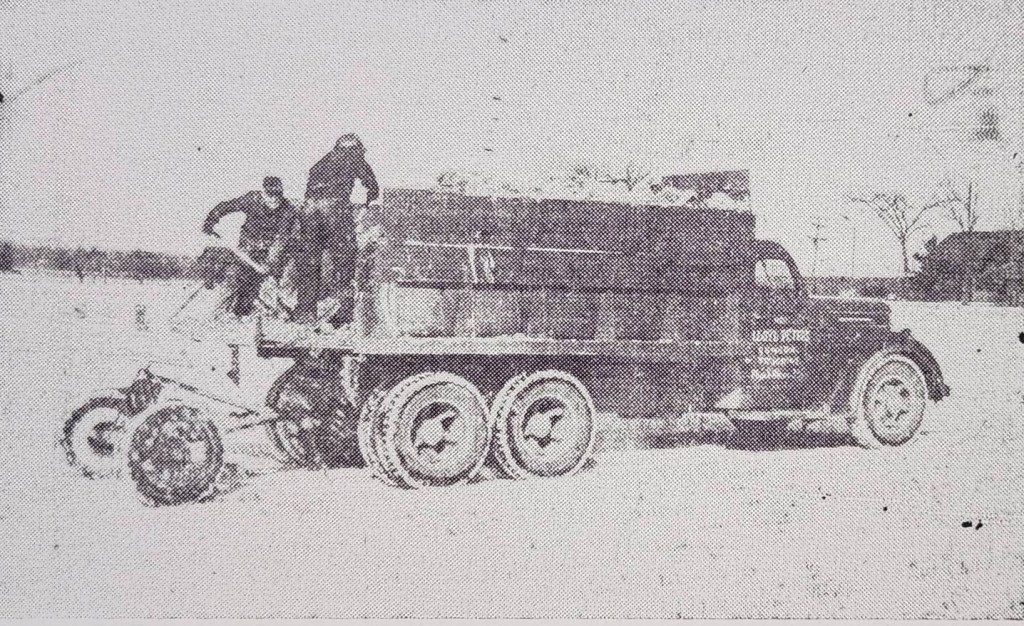

From the top: A March 4, 1941, cartoon from the St. Louis Leader illustrated how the European war affected Gratiot County’s problems with unemployment. War meant jobs; this contingent of men left Alma for Saginaw to be inducted into the Army. The photo was presumably taken at 210 East Superior Street. Another group of 49 men would leave before April 1; Lloyd Peters delivers the county’s first load of lime to the John Wertz farm in Emerson Township. Wertz ordered 16 tons for his farm with the idea that it would help production; Dr. Bernard Graham of Alma joined the Draft Board to help with physicals for men in Alma. The increased requests for more men each month meant another doctor (or two) was badly needed. Graham volunteered.

In like a lion, out like a lamb. March was supposed to be the gateway to spring in Gratiot County. Farmers held and attended various meetings in anticipation of the upcoming farming season, even though the forecasts for many crop prices seemed bleak for 1941.

However, for another forty young men from the county, they went off to the Army as part of the Selective Service – and the numbers kept growing.

New Deal programs offered help and hope for young adults in the county.

Late winter had its share of the sick.

The arm of the law kept up with lawbreakers, ensuring they were found and apprehended.

It was March 1941 in Gratiot County.

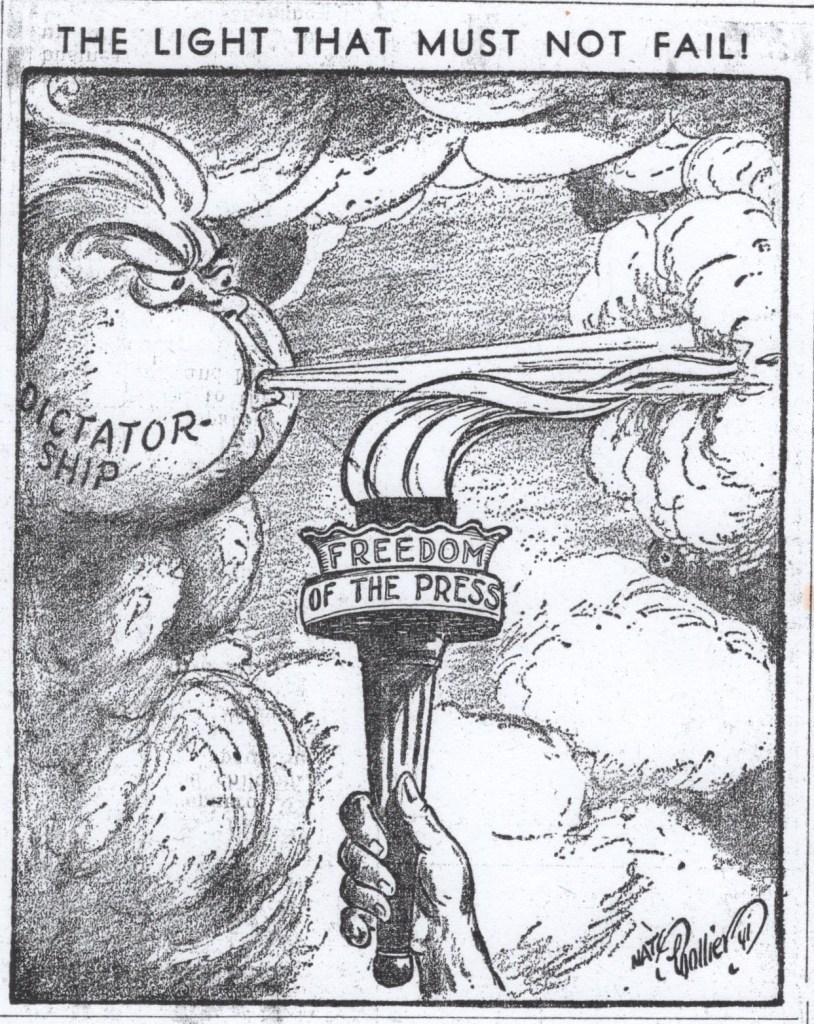

War Appears on the Horizon; Draft Continues

President Roosevelt received Senate approval of the Lend-Lease bill, which meant that America could now openly help England in its fight against the Nazis. Lend-Lease remained a matter of debate among many Americans who wanted the country to stay out of the European war. Roosevelt also warned the country needed to weather the oncoming storm, but to use the time as a means of sacrifice and service to the country. One of the greatest missions for Americans was to get involved in factory work and help to get goods to “the frontlines of Democracy.” The United States Attorney General stated the nation had 6,249 aliens who needed to be deported. The A.G. also stated that anyone belonging to the Communist Party or the German-American Bund should also be deported as illegal aliens. A bill at work in the House of Representatives said that these “illegals” had 90 days to leave the country or face imprisonment.

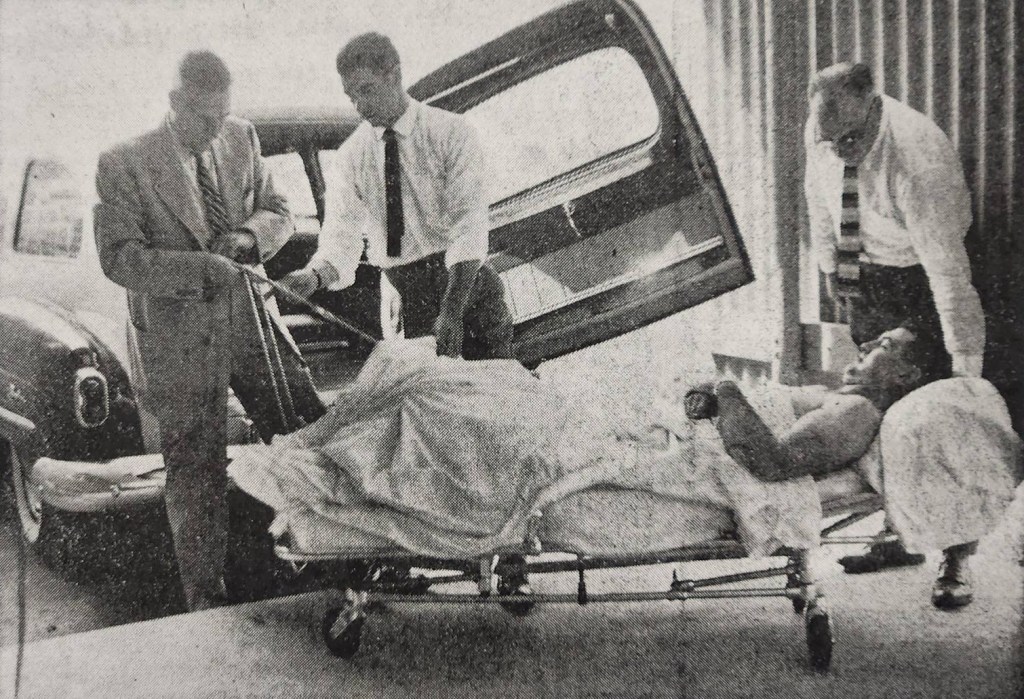

The draft continued to call more and more men into service. A total of 40 men left Alma, bringing the total number to date to 77 (50 were volunteers). A photograph of the early March contingent, presumably taken at 210 East Superior Street in front of Edith’s Beauty Shop, appeared on the front page of local newspapers. Among the group of 40 were 13 volunteers, including Elwin Gillis of Breckenridge, Michael Hospodar of Perrinton, and George Martin of St. Louis. In one of the photos, a dog could be seen running in front of the group of men just as the picture was taken. Five of the men were eventually sent back home because they did not pass their physical.

Not very long after this group left Alma, the draft board announced that April’s call for men would rise to 49 and that the group would leave for Detroit on March 31. In order to help with the growing number of draftees in Alma, Dr. Bernard Graham was added to the draft medical examining board, along with Dr. John Rottschafer.

Because the Army wanted to double the size of its armored force, those drafted or in the National Guard could be kept in service for over a year. Members of the reorganized Troop B, 106th Cavalry, National Guard, prepared for actual induction to the Army on April 1. Captain Howard Freedman stated that 70 enlisted men and three officers made up this group. They would head to Fort Knox, Kentucky. A Navy representative visited the Alma Post Office on March 14 to interview men aged 17 to 31 as possible candidates. Ronald Charles Wood enlisted in the Marine Corps and ended up at San Diego, California. A St. Louis graduate, he attended Central State Teachers College for one year and now wanted to be involved with aerial photography after completing his training.

Gratiot County newspaper readers did not know it yet, but a pattern started regarding news from young men who would be involved in war. Robert Nesen, a former employee at the St. Louis Post Office, took a course in aeronautical engineering at the Curtiss-Wright Technical Institute in Los Angeles, California. The school was one of seven in the country that trained mechanics for the Army. Francis Henry Miller of Ithaca, who left in the January contingent of men, wrote from Fort Baker in San Francisco, California. He took up cooking, trained on 12-inch guns, and found the colors of green trees and flowers in bloom to be strange to see. He was one of two boys who left Alma in that group. Then there was Lieutenant Reynolds B. Smith, originally from Alma, who spoke to the Alma Rotary Club about his experiences as a graduate of the United States Naval Academy. He now oversaw a shipbuilding assignment at Bay City. Smith would be the first Alma man killed in World War II. Mrs. George Tangalakis of St. Louis announced that she received word that two members of her family had been wounded while fighting in the Balkans. This was the first word Tangalakis received about her family in several months.

Sad news arrived in St. Louis that Leslie E. McGill, a World War veteran, unexpectedly died in the Veterans Hospital in Indianapolis, Indiana. Although he had been there for eight weeks for treatment as a “shell victim” (probably shell-shock), it was believed that he was recovering and received encouraging reports about his condition. McGill entered the war at age 18 and, after returning to civilian life, became a purchaser of airplane engines for General Motors. McGill also passed on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the death of his grandmother, Mrs. Harvey Atwell, of St. Louis, a well-known citizen.

More of the Depression and New Deal Programs

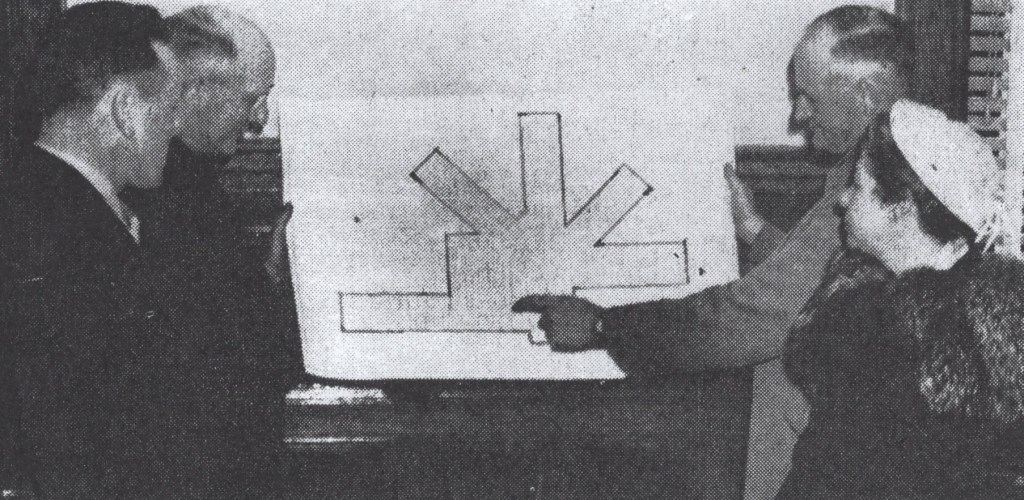

If a person in Gratiot County wanted to see a New Deal program at work, they would have observed the New Deal Youth Administration (NYA) or the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The Washington School in Alma continued to undergo work to repair the building for a boys’ workshop. The upper floor of the school would also be used for a girls’ sewing, weaving, and hot lunch project. LeRoy Layman and Mrs. John S. Morgan, both of Alma, oversaw the programs.

The WPA merged Gratiot and Midland counties to create a new area headed by Darrell Milstead, who came to Alma last August. Lester Fillhard, Milstead’s assistant, took over much of the oversight of the Gratiot County program. WPA recreation projects now existed in Alma, St. Louis, Riverdale, Midland, and Coleman. The toy library project in Alma remained very popular in the community, with 80 boys and girls checking out toys. The WPA also held a “Kite Karnival” contest on March 22 at Cavalry Field, offering eight categories for entrants. Another contest took place on March 29, courtesy of the Gratiot County Herald, and took place simultaneously in Riverdale, Breckenridge, Perrinton, Ithaca, and Ashley. The Herald planned on awarding 40 silver medals to first-place winners in eight events. Some of the Alma winners included: Darrell Milstead, Jr., youngest flyer; Marion McCormick, best homemade kite; and Bennie Sammons, longest string out.

Another New Deal program, Social Security, held a presentation at the St. Louis Rotary Club meeting. Mr. Ramsey, from the Social Security Office in Saginaw, used sound slides to illustrate how phases of the Social Security program worked and how it applied to different types of workers. Townsend Club Number 2 met at the Ithaca village hall for their regular meeting. The Townsend Plan was believed to be an alternative to Social Security and had many interested followers in Gratiot County.

Job opportunities seemed to accompany the rumblings of war. At least ten types of openings appeared at the State Employment District Office in Alma’s city hall. Jobs such as sewing machine operators and automatic screw machine operators were needed. W.N. Irish, manager of the Alma office, said that a statewide drive to find workers for national defense jobs was now in effect, and workers were needed.

Farmers and Farming Issues in March 1941

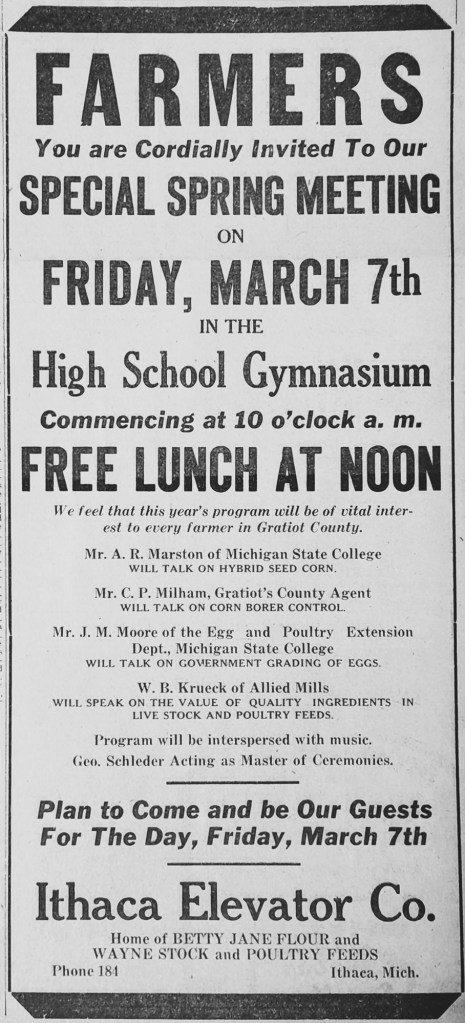

One of the main events in Gratiot County in March 1941 was a series of meetings with farmers. A group of 82 people met for a rural-urban meeting at Elm Hall. In the group were 38 Rotarians who wanted to promote good relations between farmers and club members. All enjoyed a chicken dinner prepared by the Ladies Aid of Elm Hall church.

The Alma Beet Growers Association held its annual meeting at the Strand Theater in Alma. A series of lectures and programs ran throughout the day, with a lunch break at area restaurants. A group of over 1,100 farmers and their wives attended the meeting. Over in Saginaw, another 250 Gratiot farmers attended a meeting with farmers from the Central Michigan area. One of the main issues in these meetings concerned marketing the large grain surpluses anticipated in the fall and shrinking overseas markets due to the war. Another concern that farmers faced centered around the drop in sugar sales. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reduced its acreage allotment by 18 percent for 1941.

A variety of other items made the news on the farm. Brauher and Purdy of Ithaca advertised the 1940 Massey-Harris Clipper threshing model. The business also held a Massey-Harris Farm Equipment meeting on March 12 and offered free moving pictures to those interested in learning about new products. The State Highway Conference distributed new county-wide maps that showed the county, mile by mile, with highways, roads, and streets. The Gratiot County Road Commission received the map for use in improvements and maintenance operations. Farmers continued to watch the issue of banning Sunday hunting in the county. A state law appeared to be on the way, then stalled in the legislature. Some farmers liked the idea of no hunting in order to keep out-of-county hunters away from their property. Another group in the county believed that Sundays were the only time they got to hunt. The debate went on. Area hunting groups continued to meet and discuss maintenance of their own hunting areas in the county. Topics such as trespass, sportsmanship, game law violations, and property destruction were discussed.

The first lime spreading in the county took place on the John Wertz farm in Emerson Township. Wertz received lime by calling the Agricultural Conservation office in Ithaca. The AAA farm program promoted the use of lime in order to improve farming across the nation. Lloyd Peters delivered the lime. The Gratiot County Herald featured a front-page article about John Swartzmiller, age 91, of Ithaca. Swartzmiller recalled seeing Abraham Lincoln as a boy in Tiffin, Ohio. Swartzmiller first came to North Star Township in 1878, cleared land, and put up a house in 1886. Now, he was still active at his home on East Center Street. Finally, Howard Evitts, Gratiot County dog warden, swore out eight warrants for those who had not paid their 1940 dog tax. Although 750 owners were delinquent at one time, only a dozen were left unpaid by March. The warden estimated a total of 6,000 dogs in Gratiot County. Jack Aldrich, 19, of St. Louis, was sentenced to 10 days in jail, a fine, and costs totaling $9.25 for failing to pay his dog tax.

Health and Health Issues

With the arrival of the Easter Season, news about Easter Seals came. This March campaign was the eighth annual in Gratiot County and benefited handicapped children. A group of twenty-four people made up the chairmen’s committee and worked with all area schools to ask children to sell Easter Seals. All four Rotary Clubs in the county supported the drive, as $298.51 had been raised in the campaign in 1940. Some of those helped by the 1940 campaign received corrective shoes and medicines from the University Hospital in Ann Arbor. The debate and call for a county health unit continued as chairman John D. Kelly of St. Louis informed the public about the need for the organization. Chief among the positions was that of sanitary engineer, whose duties included safe water supplies, clean and safe milk, stream pollution, and sanitation at restaurants, campsites, and picnic grounds. The projected cost of a functioning health unit in Gratiot County was estimated at $14,000 to 16,000 annually, with a doctor serving as the health officer earning $4,000 annually.

Some health news in March proved sad and alarming. Young Thomas Wilbur Hubbard, nearly four years old, died from an attack of influenza, followed by measles and pneumonia, in Lansing Hospital. He had two siblings and was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Wilbur Howard of Ithaca. Mrs. George Garrett, 48, from Porter Township, died from second and third-degree burns over much of her body after an explosion in her home. Garrett attempted to take off grease from work clothes using gasoline. The fire also destroyed the Garrett home. Her husband was an oil field worker, and she left behind six children at home and a daughter in Cincinnati, Ohio.

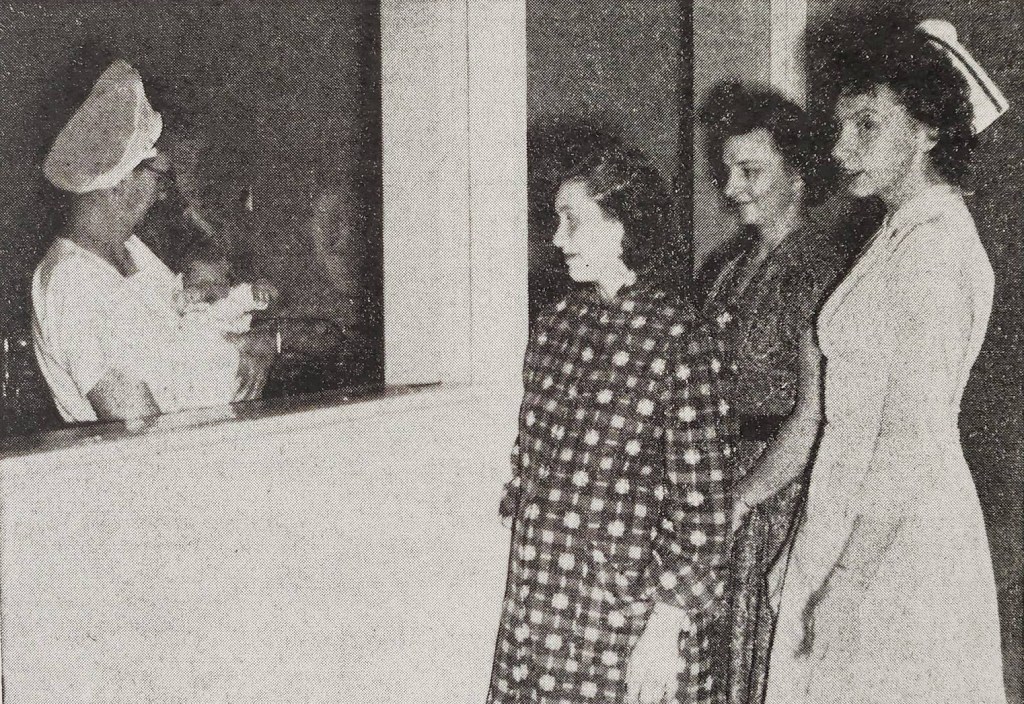

The biggest health-related story in March 1941 in Gratiot County involved migrant labor and a young girl’s operation at Carson City Hospital. Frank Vargez, 45, a beet worker on the Dennis O’Connell farm in North Shade Township, was arrested on charges of statutory rape involving a 12-year-old Mexican girl. Vargez lived with the girl’s family and supported them financially. After the girl was taken to Carson City, she safely delivered a healthy seven-pound boy via c-section. It turned out that a group of 50 osteopaths visiting the hospital for the dedication of a new wing observed the birth. The news of the patient and the baby traveled far in Michigan and made the front page of several newspapers. As soon as word reached the sheriff’s office in Ithaca, Vargez was arrested and taken to jail on $1,000 bond. The girl’s father was incapacitated and unable to work, and the family recognized that Vargas was the father of the child and provider for the family, with no apparent outward concern. Vargez awaited trial as March ended, and Gratiot County received considerable publicity regarding the arrest.

The Long Arm of the Law in March 1941

Prosecuting Attorney Robert H. Baker reported 51 convictions and 4 dismissals for February. Among these were two convictions for failure to pay dog taxes, driving away with someone’s vehicle, and removal of improperly vaccinated hogs. The courts received $151.30 in fines and $186.55 in total costs.

An interesting series of offenders and their stories found their way into county newspapers. William Farrell of Alma was charged with indecent conduct by two CCC boys he picked up on the highway. That trial was yet to come. Herman Ginsberg and George Foster, who said they represented Consumers Supply Company of Saginaw, were arrested for selling silverware without a license. Both men argued that they sold on time-payment plans and accepted sales tax as a down payment. Future time payments were then to be made by the purchaser. They also claimed they were exploring the possibilities of setting up an Alma store. Both challenged the city ordinances on permits to peddle, and both lost in court. Their fines exceeded the cost of buying a permit in the first place.

A third Saginaw man, Walter Granger, was arrested and convicted in a strike disorder case. Granger was one of a series of men who interfered with an oil truck delivery during a strike in Alma. He got a $60 fine or 60 days in jail. He took the fine. Granger was also represented by a Saginaw attorney. In a lighter story, “aged derelict” Mary Buckler, 67 of Gaylord, asked for a night’s stay in the county jail after being stranded in Ithaca. Upon arrival in her “accommodations” for the night, the snow-white-haired Buckler popped out a package of cigarettes, lit one up, and declared that it was her only bad habit – and that it was not an addiction.

Local law officials were also involved in a pair of serious accidents in the county. A crash involving four cars and a cattle truck at the garage corners at Wheeler and M-46 occurred when Foster McAllister tried to duck between the cars and an oncoming truck, smashing up cars and gas pumps at a nearby gas station. Damages were estimated at $1,000, and one 14-year-old was sent to Smith Memorial Hospital for treatment for cuts and bruises. Stanley Furley suffered a skull fracture and was unconscious. McAllister did not judge the distances of oncoming vehicles and did not see oncoming traffic. Another couple and their family were seriously injured northwest of Alma at the Bartley Crossing when the car of Earl Clifton Ray hit an oncoming locomotive of a southbound passenger train. Ray died, and his wife lost part of her right leg. Two children were less seriously injured and treated. Mrs. Ray also suffered a broken right arm.

Sheriff William Nestle was involved in an operation at Smith Memorial and was sent home to recover. Things appeared to be going well for the sheriff in terms of recovery.

And So We Do Not Forget

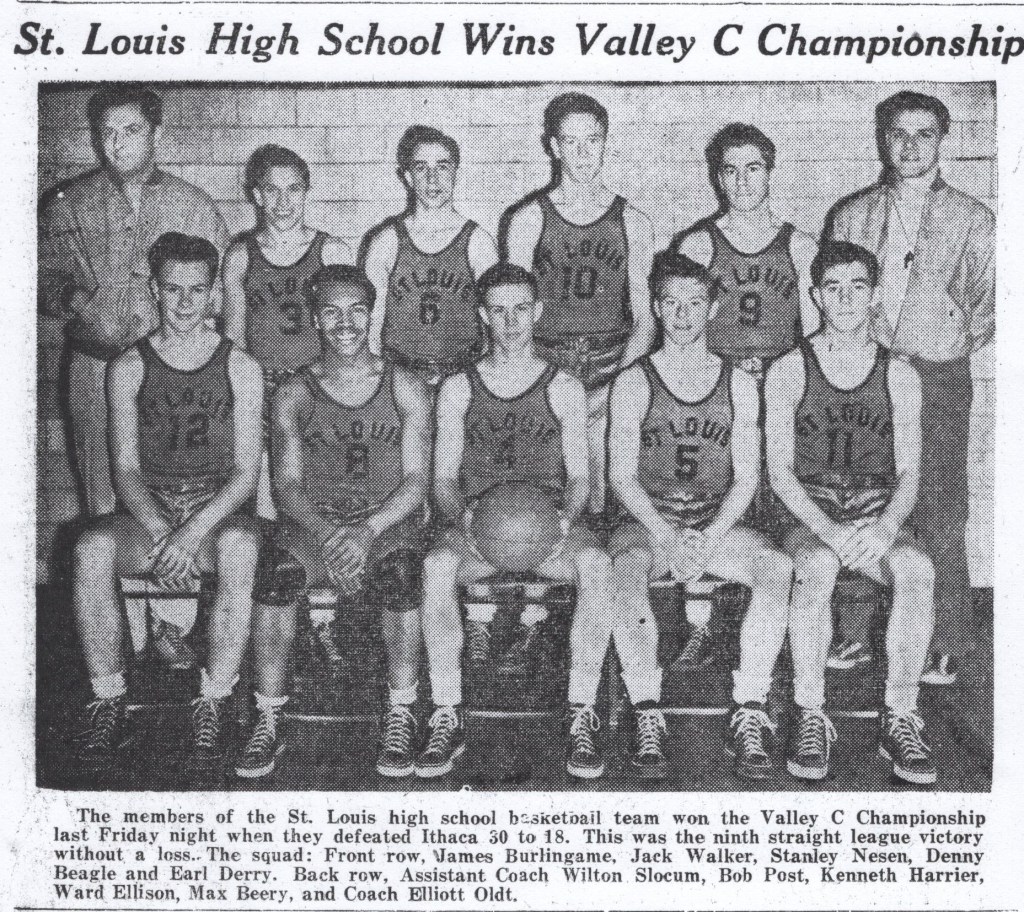

Former St. Louis graduates Maurice Pernert, Marshall Greene, Hilmer Leyrer, and Elliott Oldt (who moved to St. Louis early in life) were all successful basketball coaches at various locations across the state. Coach Oldt led St. Louis to its second championship (one in football, the other in basketball)…Both city workers and NYA youths helped to clean St. Louis sidewalks and streets after a heavy storm in early March. Snowball-throwing by kids was strictly monitored and enforced…Mrs. Park Strouse of Wheeler wrote a long column about her trip to Texas and Mexico. She noted that the Rio Grande Valley was full of American tourists…Kernen’s Style Shoppe sold new spring sweaters in pastel shades for a dollar…Lieutenant Reynolds B. Smith, United States naval officer, spoke to the Alma Rotary Club. Smith was stationed in the Bay City shipyards and oversaw the construction of a naval vessel…The early March snowstorm and cold snap held up the tapping of trees in Alma’s Conservation Park. Tapping of Maple trees was set to begin when the weather changed…Sawkins Music House in Alma announced its newly remodeled basement, which sells refrigerators, stoves, and washing machines. The floor received new linoleum and lighting.

A cast of sixty men performed “Womanless Wedding” at the Ideal Theatre in Ithaca. Made by locals, the play was a big hit, drawing a large crowd…Gladys Peters of Ithaca’s Reliable Tire Shop was featured as general business manager on the front page of the Gratiot County Herald’s “People at Work.” A week later, J.L. Barden of Ithaca appeared. Henry McCormack was also featured in a series about people in their workplaces…Ray’s Groceries and Meats opened in St. Louis and was operated by Mr. and Mrs. Ray Boivin at 501 South Maple Street. Phone 157 for an order. Roland Mann previously owned the business…The Bethany Dunkards Club held a meeting at Mr. and Mrs. Ray Barnes’ home. They played Chinese checkers until midnight and enjoyed friedcakes, cheese, and coffee. The host and hostess received a new electric clock as a token of appreciation for the evening…Music meetings for Gratiot County rural school teachers at four places, including the Ashley gymnasium…The Fulton High School basketball team lost to Perry High School, 31-21, in a battle between western and eastern division leaders…The Gideons placed over 150 Bibles in local schools. Between 75 and 100 of them went to Alma College students…Alma City Manager W.E. Reynolds purchased a used 140-horsepower diesel engine as a backup for the city in case power went out while pumping city water. The cost was $3,000.

The St. Louis Lions Club sponsored a birdhouse contest until May 15. First prize was $1.50, and all birdhouses would be returned to their owners…The St. Louis Junior Class planned to perform ”Man Bites Dog,” a three-act play, in early April. Miss Alma Weston and Wilton Slocum, teachers, directed the play… Circuit Judge Kelly S. Searl planned to run for re-election in the 29th Judicial Circuit. He had practiced law for over 25 years…Orville L. The Church of Alma declared himself a candidate for Alma city commissioner…Once the sap started running in late March, 50 to 60 sap buckets appeared in Alma’s Conservation Park. On Sunday, March 30, a “boiling bee” was scheduled, and hopes were high that the group would exceed the 1940s results of 20 gallons of syrup…The Masonic Lodge in Middleton held a banquet at the Methodist Church, with 84 people in attendance. Green-colored decorations appeared in a St. Patrick’s Day theme…Knapp’s Bakery in St. Louis completed its second year in business. Lloyd Knapp reminded locals that he had his own delivery truck for service for his baked goods…One hospital in Alma incorporated under the new name of Carney-Wilcox-Miller Hospital, Incorporated…Alma Trailer Company on Michigan Avenue had to hire more men, possibly for a night shift, to keep up with orders for new trailers. New workers were being hired daily.

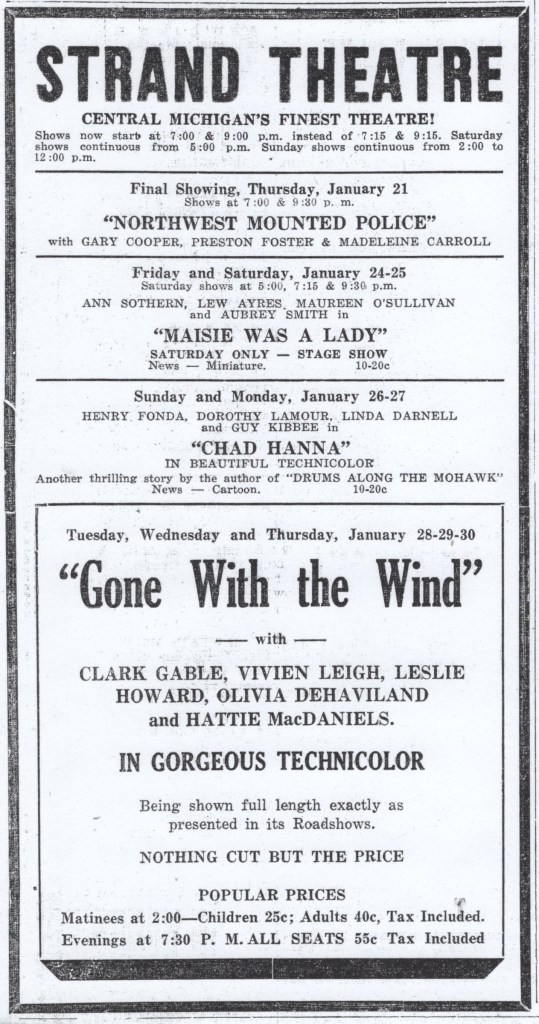

A group of pastors visited the county from March 17-21 for Lenten messages in Alma. A different church was chosen each night for speakers from Flint, Saginaw, and Midland…St. Louis High School students participated in the annual speech contest. Winona Gerhardt was in charge of the contest… Mr. and Mrs. C.F. Otto of Perrinton observed their fiftieth wedding anniversary on March 14. They lived in Perrinton for 39 years…A talk for parents in Ithaca on “Problems of the Adolescent and Sex Education” was held at the Ithaca High School gymnasium. It was hoped that husbands would be in attendance with their wives in the meeting…W.C. Fields appeared at Ithaca’s Ideal Theatre in “The Bank Dick.” Serial, Terrytoon, Stranger Than Fiction, all for only ten cents…Judge J. Lee Potts of Ithaca, age 87, planned to run again and work as a judge in Ithaca. In fact, he planned to work for several more years…The St. Louis City Council voted on a resolution to pursue plans for a new sewage disposal plant. St. Louis, like other cities along the Pine River, had been advised by the State to plan and build a new plant…”Alma Days” took place on March 21-22 to bring customers to town for a bunch of deals. See advertisements in the Alma Record-Alma Journal.

James Hamp of St. Louis received a gold medal as champion trailer coach driver. Hamp represented Alma Trailer Company at the International Sportsmen’s and Trailer Show in Chicago. Hamp drove for Alma Trailer for the last five years…Gaylord Hanley of St. Louis celebrated his fifteenth birthday. His mother and family hosted a Sunday dinner, and guests attended. Hanley later served in the Navy during World War II, saw action in New Guinea, and was tragically killed in a fall from a ship on January 26, 1944.

And that was Gratiot County during the Depression and war in March 1941.

Copyright 2026 James M. Goodspeed