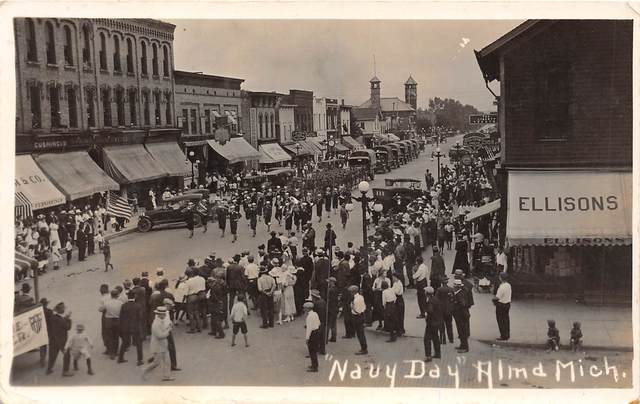

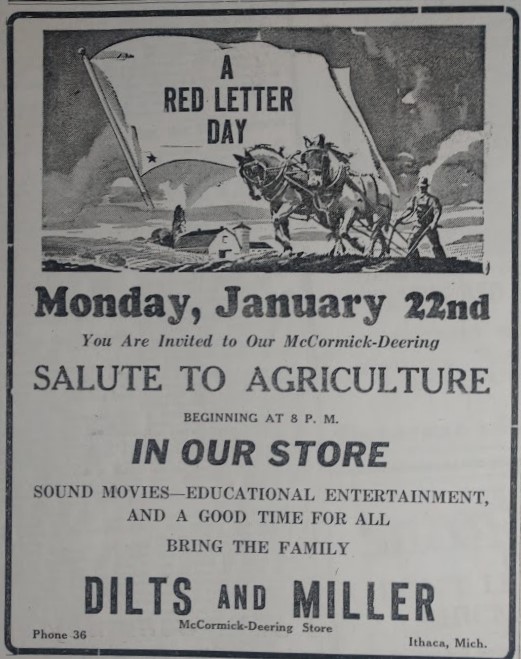

Above: Rationing violations in Gratiot County and hunters; the Farm Bureau and county banks all urged support of the war effort; farming and farm products all stayed in the minds of people as the war went on into 1945.

The surprise and the shock of the German attack in the Ardennes in December continued to make the headlines. Although the Western Allies slowly pushed the Germans back, the going was slow, and casualties continued to climb.

Out in the Pacific, the United States landed in the Philippines and began the process of liberating the islands from Japanese control. For a while, the news about the war in the Pacific seemed brighter than what was happening in Europe. County newspaper columns now warned citizens that the war in Europe could take another year to win. No projections were made about how long the war against Japan would take.

At home, the OPA cracked down on rations and rationing as a result of the Battle of the Bulge. Some foods that had been relatively easy to obtain now came under stricter guidelines. A group of Gratiot County hunters found themselves in trouble with the OPA for abusing their gasoline rations during deer season.

The war was real, it was going to continue, and the consequences were harsh.

It was January 1945 in Gratiot County.

The Red Cross

The Red Cross announced at the start of the New Year that families and friends of prisoners of war in Germany could now write immediately to their loved ones. The International Red Cross in Switzerland now accepted the letters, which used to take at least two to three months to reach a captured POW. However, packages still could not be sent until it was determined the POW’s permanent address.

School children in Gratiot County had their work displayed in the window of the county chapter’s window in Ithaca. Donations of afghans and bed slippers showed how school children supported the Red Cross. Mrs. W.L. Clise, who had worked as chairman of the Junior Red Cross for the past eight years, organized the window display.

The 1945 Red Cross fund drive was set at a goal of $25,700, and March 20-22 was set aside as county canvass days to raise money. Stanley C. Brown served as county chairman, and six other men served on the board with him, each from the five districts in Gratiot County. For example, Mrs. Ralph Tweedie was chairman for District No. 5, which consisted of North Shade, Fulton, Washington, and Elba Townships.

Different chapters in the county published their annual reports and the work they did in 1944. The St. Louis chapter published a long list of women who worked on things such as knitting for the Army and Navy, which the women there contributed 1168 hours total (Mrs. Emma Weston gave 211 hours of service). Items like sleeveless sweaters, gloves, helmets, mufflers, turtleneck sweaters, scarfs, and watch caps were many of the things that the group made. Mrs. Florence Marr submitted the report, which detailed which St. Louis women gave of their time.

At the annual Alma Red Cross Chapter meeting, Mrs. G.A. Giles was re-elected as chairman. Some of the things that the Alma group did included the creation of kit bags, Army hospital garments, and surgical dressings. Loans totaling $596 had been made to servicemen from the unit. The chapter had a fund balance of $2, 045.41 to work with to start the year

Ithaca also had a meeting on January 26 and announced that the new service headquarters had been set up across from the courthouse. Ottoway Marett, a father whose son was killed in the Pacific in 1941, spoke at its annual meeting in the Thompson Home Library. Marrett joined the American Red Cross immediately after his son’s death and went overseas in 1942. Mrs. Sarah Rasor acknowledged that 106 garments and 144 kits had been sent out in 1944.

Farming in Gratiot County

Among the most important news that involved farmers concerned the drafting of farm laborers. The War Mobilization director announced that men now between 18 and 25 years of age who had agricultural deferments would now be drafted. These workers, who made up a farm pool of approximately 345,000 men in the nation, was the last large source of men for the war. The German offensive in the Ardennes in December pushed back expectations that the war in Europe would soon end, and more soldiers were needed. Once the drafting of deferred farmworkers was announced, farmers across the state voiced concerns that they could not meet the nation’s farm goals for 1945. Some farmers were livid when they heard that they would lose their farm help. In some places in Michigan, farmers went to the draft board meeting, walked in with farm animals such as chickens or a cow, and left them with the draft board. The farmers then told draft board members to figure out how to feed and take care of the animals.

A group of about 350 young Gratiot farmers was called up for pre-induction physical exams. Five busses, consisting of 175 men, left early in January with another group scheduled to go in February. Usually, the examinations were given 30 to 40 days before induction, but the draft board could not confirm how soon these men would be inducted. Michigan was expected to send 35,000 men by July, with 10,000 of the men coming from deferred farmworkers.

In other farm news concerning Gratiot County, St. Louis schools announced that it was offering adult classes in agriculture. Ithaca, grain market news, reported the following prices: No. 2 White Wheat sold for $1.64 a bushel; Dark Red Kidney Beans were $7.25; live poultry went for 25 cents a pound; U.S. graded eggs sold between 24 to 40 cents a dozen. Arlan Sherman from Ithaca appeared in the January issue of Capper’s Farmer with his invention, which involved using an old inner tube as a tractor cushion. Sherman wrapped his cushion in an old burlap sack, shaped into the desired shape, then tied it to his tractor seat. Dairy feed payments for milk and cream subsidies became available in late January in four different towns to save farmers from driving long distances in Elwell, Middleton, Breckenridge, and Ashley starting January 1. St. Louis Beet Growers Association held its fourteenth annual meeting in the St. Louis High School auditorium. A free lunch was given to those who attended. The St. Louis Cooperative Creamery also planned its annual meeting for February and planned on having it in the high school as well. Farm families were urged to comply with the 1945 Census for Agriculture, and a call went out for help from people to enumerate the census. Farmers could also obtain certificates for lumber to be used for maintaining or repairing farm dwellings. While pumps and cellar drains were still rationed, household water systems, like sump pumps, were not.

Another problem concerned the number of people who held auction sales because due to a lack of help. Or, farmers now were being drafted. Maynard Parrish of North Star, Paul Duski of Bannister, Robert Chaffin of Ithaca, and Ciril Tugen of Alma all were forced to sell because of military obligations. Joe Honus of Ashley had no pasture for his animals, so he had an auction sale. Allen and Orville Ropp quit farming “at the request of the draft board,” and so they sold their farm west of Alma.

Some exciting developments occurred in the county concerning the hunting of red foxes by hunters and farmers. Gratiot, Clinton, Ionia, and Montcalm hunters all declared war on red fox as it was believed that the animal was decimating the pheasant population and preying on farm animals. On Christmas Eve, an organized fox hunt started in Maple Rapids, led by Conservation Officer Harold Barrow and fifty hunters, bagged five foxes. Not one of the hunters volunteered to turn in a fox for the $5 bounty for animals that were shot in North Star and Newark townships. One of the foxes had to be dug out of its burrow. Nineteen of the hunters had their picture taken which appeared on the front page of the Gratiot County Herald. There had been some debate in Gratiot County about the new $5 fox bounty. Sheriff Nestle had to examine all fox pelts, and he then placed a unique perforated stamp in the ear of each hide. The mark prevented anyone from cheating and collecting twice on fox pelts.

On a more promising note, Union Telephone Company said that it planned to expand rural telephone service “As soon as war demands are reduced…” The announcement encouraged many Gratiot County farm families as rural service did not extend to that many in the county.

Rationing Goes On

As rationing continued in January, it seemed to be even more severe than it had in 1944. The Gratiot County rationing board issued certificates for 97 Grade 1 tires and 21 small truck tires. Later in the month, the rationing board issued another 270 tire certificates. Another potentially rationed item dealt with a possible coal shortage. Now, people were warned that they might have to obtain certificates indicating their need for coal. In January, the lack of coal had not hit. However, concerns over fuel started to appear. The anticipated coal shortage would lead to “brownouts” in St. Louis as the War Production Board wanted a drastic cut in the amount of electricity to be used after February 1. This rule meant no exterior lighting for display purposes, and only lights for public safety and directions to the downtown area would be allowed. The welcome sign to St. Louis also was turned off.

The German December offensive affected rationing. Before Christmas, only one-third of meats had been rationed; now, 85 percent of beef on the ration list was rationed.

Centers in the county continued to request tin can collections. Trucks went to ten places in the county starting January 15 and delivered tin to the Harris Milling Company in Alma. The Moblo Hardware Store in Riverdale and Sumner Hoxie Store in Elwell were just two of the places that tin could be taken locally. The tin from Gratiot County went to the Vulcan Detinning Company in Pennsylvania, and a total of over seven tons of tin were picked up from the back of Alma City Hall. When it was all done, Gratiot County sent over ten tons of tin from a year’s worth of tin drives.

Superintendent F.R. Phillips of Alma Schools proclaimed that Alma students would help pick up the paper at the same time as the tin drive. During the day of the tin drive, Alma students took approximately one hour after school to pick up over one ton of tin that day. Eight trucks and drivers assisted the students. Anyone who missed having their paper ready for the pickup only needed to call the Civilian Defense Agency at Telephone 103. Breckenridge also held a two-week tin drive, and tin was delivered to the Miller Implement Store. The Breckenridge Blue Star Mothers encouraged people there to help make an extensive tin collection in the village.

The city of Alma already started a “paper holiday” after the holidays. The Chamber of Commerce urged shoppers to bring a bag for their purchased items instead of asking to be wrapped. One of the calls for the paper during the war now concerned cartons for shipping blood plasma to wounded soldiers. Over in St. Louis, the Boy Scouts planned another paper drive pickup in early February.

Over at the Ithaca courthouse, a group of 27 Gratiot County deer hunters were summoned by the OPA authorities regarding the misuse of gas ration cards. Several Gratiot hunters exceeded their gasoline allotments in traveling to the Upper Penninsula to go deer hunting. Drivers had only 120 miles per month in gas rations, and they would have had to save over three month’s worth of rationing allotments to travel that far north to hunt (which amounted to 360 miles of travel). When the men were confronted with the fact that their travels exceeded 406 miles to and from the Straits of Mackinac things, plus mileage beyond the Straits, things did not seem to add up. As a result of the hearings, the men received 90-day suspensions all gas rations. Some of these men included Archie Mates (Breckenridge), along with E.A. Cummings, Philip Becker, and Joseph Kapral (Ithaca), who received 90-day gas ration suspensions. Another three men who did not appear in court got 180 day suspensions. The hearings , led by OPA officials, took place in the supervisors’ room in the courthouse.

A New Direction for the Draft

The December German offensive sent ripples through Gratiot County because the military looked for more fighting men. Selective service looked for those previously classified as 4-F, as well as those who had deferments as farm help. President Roosevelt admonished those who committed “job skipping” – those who left their designated jobs without approval from their draft board.

One of the changes in Gratiot County dealt with men who previously had been classified as 2-A now had 1-A classifications. These included young business and professional men. Clerks and telephone operators – as well as postal carriers – all received the news that new draft orders were coming. County Farm Bureaus asked Draft Boards to slow down and carefully consider who would now be drafted. The main argument for this centered around the effect that drafting farm boys had on the effectiveness of farm help and crops for 1945.

War Bonds and Loans

The final report for December’s Sixth War Loan Drive showed that Gratiot County raised just over $449,427.00 or 64 percent of its goal for sales to individuals. Corporation sales, however, went above the target and raised $579,795.00, or 143 percent of its aim. Overall, Gratiot County raised over 93 percent of the assigned goal it had for selling war bonds in the drive, which turned out better than had been projected. Why didn’t the county do better? County newspapers asked the same thing and reminded the public that there was no better duty than investing in the government as many hoped that the war in Europe would soon end.

There had been other successes with bonds. A former St. Louis lady, Mrs. Clinton Bailey, now lived in Detroit. Bailey sold over $100,000 in bonds over the previous two years and gained headlines when she sold a $50,000 bond for the American Women’s Voluntary Services. Over in Pompeii, Miss Cheryl Lynn Fraker received a $25 bond as the firstborn child in 1945 in Gratiot County. “Miss Gratiot of 1945” was born at Smith Memorial Hospital at 3:15 a.m. on New Year’s Day. She weighed 8 pounds 3 ounces, and Dr. A.L. Aldrich attended the delivery, with help from Gertrude Kirby, the Registered Nurse.

Letters Home to Gratiot County

Letters home to Gratiot County reminded readers who were defending the homeland. Private Berfield Acker wrote to his parents in Alma about being in the South Pacific. Now in the Philippine Islands, Acker said he had lost some weight. He also had never been so unclean in his life. He had been living in dirt and mud holes for over a week. The dirt on his clothes made them very heavy and he had to clean them by beating them against a rock while standing in a creek. After being allowed to trade with the natives, he and his fellow men obtained bananas, chickens, and sweet potatoes. Although he had yet to receive Christmas presents from home, Acker enjoyed turkey for Thanksgiving. Orville Lippert, also from Alma and in the Pacific, got his letter and pictures from home in time for Christmas. Lippert visited a Catholic chaplain at one of his stops and was asked to paint an image on the altar for the chapel. He took pictures of where he was and hoped that they would arrive home by March. Lippert also wrote that he spent a lot of time interacting with the natives in his area by learning how to ride in a canoe, which he almost tipped over.

Leland Lytle wrote home from Holland, asking for someone to send him cigarettes. Lyle served with the engineers and valued hearing from his mother – “Hearing from you is almost like hearing your voice.” Officer Clair Purdy of Alma told his voyage to England. Purdy said that the men only ate twice a day, and he was on a British ship. As an officer, he had excellent quarters, and he had a steward clean his room twice a day. Everyone on board took showers and baths in saltwater as freshwater was used only for shaving and drinking. English stewards gave table service to the officers while enlisted men had to eat out of their mess kits in the chow line. The seas could be rough, and when Purdy reached once for his coffee, “I found it wasn’t there but had slid halfway down the table. At the same time, a crash in the kitchen indicated a tray of broken dishes.” Several civilians also were on board, traveling under government authorization as foreign diplomats.

“Somewhere in the Pacific,” Clarence Isles wrote to his parents in Ithaca that he had been on Saipan. Isles told his mother that he had not seen a window in so long that he forgot how curtains looked. On Saipan, Isles had to search enemy dwellings and also saw many dead Japanese after a battle. He estimated at least 5,000 enemy dead lay in a ten-acre area, having fallen three or four deep due to machine gunfire. A fellow soldier claimed to have killed 58 Japanese in one night attack. The Japanese ran in large numbers, yelling, and appearing to be drunk. Isles said that frequently the attackers got through the American lines because there were too many to shoot at one time. Ronald Gross also told his parents in Ithaca that he just had not had time to write during the treacherous invasion of the Philippines. “The reason you haven’t heard from me is because I have been fighting and couldn’t write. I have had some buddies killed, but I can’t tell you how many or how,” Gross added. He did send home some Philippine money.

Donald Peters told his parents that he received packages in Italy from the Blue Star Mothers and the Sowers Church. He said it was nice to be remembered. Sergeant Max Sias wrote to his parents in St. Louis after arriving in England. Sias was in France at Christmas and attended a Christmas Eve service in an old church filled with former soldiers and some French citizens. These were the first services in the church in four years. The people there had not attended services since being occupied by the Germans. A family that owned the building where Sias and other American soldiers were billeted gave Sias a basket of apples for Christmas, a wonderful Christmas present. Private Howard Comstock, also of St. Louis, also wrote to his parents about parachuting into Holland with the 82nd Airborne. Comstock said that he had too many things on him when he jumped out of the plane, causing him to almost fall headfirst. While Comstock safely landed, he found himself in the middle of a field; then he sought cover in a ditch. As Comstock sat there for a moment, Comstock saw three C-47s hit by enemy fire before they went down in flames. Upon hitting the road, he and other paratroopers ran across a bridge nine spans long, all while being shot at by the Germans. Private Orland Keefer of Alma wrote a heartfelt letter to his wife, explaining his Christmas Dream. Keefer dreamt of hearing his wife’s voice, entering his home, and seeing a Christmas tree inside. Keefer made it clear that “I know when I go home, I’ll be sure no children of mine will ever have to spend their Christmas in jungles, in fox holes, or beachheads.” Private Donald Kiter of St. Louis wrote that he was staying in an 18th-century chateau somewhere in France. Kiter was amazed by the cloth-like wallpaper, rug, fireplace, “and almost all of the comforts of home.”

Those in the Service

Three Dancer boys from Wheeler were in Europe. Leroy (France), Kenneth (Germany), and Duane (Italy) were all involved in combat areas. Private Lowell Quidort wrote that he was now in Belgium. Corporal Mike Simonovic sent word to his wife that he was somewhere in France, possibly in Paris. Private Frank Wroe of Elwell served as an ammunition worker in the 8th Air Force B-17 Flying Fortress station in England. Private Frank Raymond wrote to his mother in St. Louis from a foxhole in Germany with the Third Army. He said that his hole was not too wet. Corporal Alfred Gorringe of Alma was an MP with the Sixth Army Group Headquarters in France. He was involved with traffic patrol, headquarters guard duty, and town patrol work. Private Donald Greening of St. Louis told his parents that his Christmas dinner in Belgium during the German offensive consisted of cold beans and some hard crackers. Greening served with the Cannon Company of the 290th Infantry. Second Lieutenant Stanley Bailey, Jr., of Breckenridge, piloted the troop carrier “Dakota” over Cherbourg on the opening night of the invasion and now did so over Holland. He had worked for Greening Oil Company before entering the service in April 1942.

In Italy, Private Matthew Horwath served as a carpenter with Peninsular Base Section Ordnance Depot. His unit serviced combat troops throughout the Mediterranean. Russell Isham of Middleton served in the signal company of the 100th Infantry Division in the 7th Army front. Isham’s unit was in charge of communications. He had gotten as close as the Rhine River. Private James Mills of North Star served in Italy with the 11th Bomb Group of the 42nd Bombardment Wing. He had been involved in five campaigns since going overseas two years ago. Private Leland Perry of Alma wrote from Italy, thanking his parents for the “swell” Christmas he had after receiving twelve Christmas packages. This was the second Christmas Perry spent in Italy. Private Glen Mutchler, also of Alma, served with the 339th Polar Bear Regiment in Italy, which broke the German Gothic Line at places like Highway Line and Futa Pass.

Robert C. Ode of St. Louis was serving on an LST in the South Pacific. Emery Bebow of St. Louis returned to California to await his second deployment to the Pacific Theatre. Lorne Beard, who was inducted into the Navy before graduating from St. Louis, served aboard the USS Boise and saw action at New Guinea, Guadalcanal, and now in Leyte, Philippines. He had two brothers in the service as well. Sergeant G.D.Smith of Alma sent home a picture from a New Guinea jungle of a Papuan native doctor. The natives were very helpful during the invasion, and they helped fight the Japanese. Harry Most of Lafayette Township finally got word home to his parents that he was okay. He landed in England, and his brother James made it safely to France. A third brother, Bert, saw a lot of action in New Guinea and wished he could see snow back home in Michigan. Nolan MacLaren of New Haven wrote from the South Pacific that he received his Christmas package and all of his cards. He commented on how the men he served with valued Christmas treats and how they shared them. MacLaren thought he was relatively safe and hoped to see Japan when the war ended. MacLaren also hoped he would return through New York so that he could say that he had been around the world.

In the United States, Private Leonard Zinn was in Fort McClellan, Alabama, and “is very lonesome and would welcome letters from any of his friends.” Sergeant Elon Pratt went back to Jackson, Mississippi, with his wife after a fifteen-day furlough. Pratt had spent 30 months in Alaska with the 11th Air Force in the Army Air Corps before coming home. Private Reed Gould also came back on a three-week leave from India. It was his first furlough home since entering the service in 1941. Staff Sergeant Robert Duane came home from Italy after completing 50 missions in the Air Corps. He expected to be sent to Miami, Florida, after his two-week visit. Technical Sergeant Richard Guernsey came home to Middleton after completing 51 missions as a radioman and gunner in Italy. He departed for Italy on July 1, 1944.

Finally, news arrived that Private Evelyn Courey now served as a staff car driver with the North Atlantic Division of the Air at LaGuardia Field in New York. Courey had been a WAC since early December 1943, and her mother lived in Alma.

Those Killed, Wounded, and Missing in Action; Status of POWs

The number of names of those who died in service to Gratiot County and the nation continued to grow. In 1944, at least 49 young men from the county or neighboring areas perished while defending the United States.

Lieutenant Arner, Miles Douglas of Ithaca, died in France when his P-47 Thunderbolt crashed in dense fog on December 2. Douglas had already survived being shot down during the summer of 1944 in his plane, “Miss Isabelle.” Had Douglas completed his mission he would have been eligible for a furlough home. Another loss from Ashley occurred when Sergeant Robert Kerr was killed in action, as was Lieutenant Leslie Struble of St. Louis. Both deaths were tied to the German offensive in Belgium. Private Robert Lucas was also killed in action in Belgium on December 28. He had attended St. Louis schools and had been in the service since late March 1942. Sergeant Edward Lyon of Ithaca died in an airplane crash in England on January 2 as a result of the fog. Ray Bartlett, a Fireman 1/c from St. Louis who had been listed as missing in action in the South Pacific, was now listed as dead. Orville Casson, age 18 and whose grandmother lived in Ithaca, died when his ship the USS Destroyer Monaghan went down during a typhoon in the Western Pacific. Only 6 out of 150 men on board survived. Casson’s cousin also lost his life in the Pacific aboard the U.S. Submarine Grunion.

The American Legion held a memorial service in Breckenridge for Private Donald Armbrustmacher, who was killed in action on October 31, 1944. The ceremony took place at the Congregational Church, which was filled with family, community members, and members of the Blue Star Mothers. Taps was played at the end of the service. Another memorial service in Breckenridge took place to remember Quartermaster Denver Welch, who lost his life in a hurricane on September 18, 1944. Welch had been aboard the Coast Guard cutter The Jackson when lost in the Atlantic off Cape Hatteras. Welch’s death marked the second time in the service of his country, having enlisted at age 18 and spending six months in the Panama Canal Zone. After being discharged due to a bone infection, Welch re-enlisted in December 1941 and joined the Coast Guard. Earlier in May 1944, Welch spent a week in a life raft at sea when he lost his ship in a storm.

The names of the wounded from Gratiot County kept growing. Private Alfred Reed was wounded at Aachen and now was in the 162nd General Hospital in England. Private Kenneth Burch from the Porter Oil Field was in a hospital somewhere in England. Private Frederick Rohn had spent five months in a hospital in England, but he was now back in action. Others wounded in Europe included Private John Meyers of Sumner, Corporal Jack Dickerson of Alma, and Lieutenant Carroll McAdam of Ithaca. However, there had not been much information about any of them. Sergeant Daniel Dafoe of Alma suffered a shell fragment to his upper right arm on Christmas Day in France, but he was making a healthy recovery. Another Alma man, Lieutenant Frank Shimunek, suffered a severe shoulder wound in Northern Italy while commanding his platoon of combat engineers with the 88th Blue Devil Division. He would be out for at least two months. Private James Fox of Alma, who previously served as an MP and had been transferred to the Infantry, was wounded during the Belgium break-through. T/4 Ray Ferrall of Bannister also injured his right arm on December 20 and would be out four to six weeks. Private Carl Wiltfong of Ithaca was wounded on Christmas Day in Germany, but he expected to rejoin the 121st Infantry soon.

Out in the Pacific, Private Wayne Sowers was wounded on Guam in July and was hospitalized. He enlisted at age 18 and received the Purple Heart for his wounds. Arthur Lover from Bannister was in a Naval hospital in the South Pacific. Private Wayne Sowers of St. Louis had been wounded while on Guam and spent two weeks in the hospital earlier in July.

Some of the most significant anxiety that Gratiot County families dealt with concerned about the unknown status of several men. Lieutenant John Ellis of Alma was missing in Belgium, as Sergeant Duane Rench, who was missing from a bombing raid over Germany. Others missing in action included Private Arthur Wilson (Breckenridge), Jack Little and Ted Barton (North Star), Duane Rench (Alma), and John Kupres (St. Louis). With each of these men, little was known about their fate except what the War Department announced. On New Year’s Day in Alma, the wife of Lieutenant Harold Fandell learned that her husband had been missing on a B-24 bombing raid on December 12. One week after receiving this news, she learned that Fandell was back with the Eighth Air Force in England because he survived the bailout over Germany. Mrs.Henry Isham of Middleton discovered that her son, Lieutenant Robert Perry, was missing since a September 22 bombing mission from India to China. Perry piloted a C-46 cargo plane. Private Foster Gervin of Elm Hall had been missing since December 4 in Germany.

More Gratiot men also became prisoners of war, mainly in Germany. Erwin Junior Morey, whose mother lived in Wheeler, sent a card to his mother saying that he was well, and the Red Cross brought food to his camp once a week. Private Anson Foster, who had been missing since September 15, now was a prisoner of war in Germany. So was Sergeant James Grosskopf of Alma, who had been in a camp since December 11, 1943. Sergeant George Mahin of Alma also was in the same camp.

And So We Do Not Forget

The Gratiot County clerk released figures that one divorce in every 2.75 marriages in the county during 1944. The record showed 244 marriages and a total of 81 divorces were granted…The Gratiot County Road Commission planned to construct four new steel and concrete bridges in the county and 4 ½ miles of a new highway. The total cost of these post-war projects was estimated at $435,000…The Gratiot County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously in favor of Gratiot County and the state of Michigan going to Central War Time (Eastern Standard Time)…A crazed Leslie man shot and killed one person and wounded another near Elm Hall in early January. Nally King shot his former housekeeper and her mother when Mrs. Marian Blair refused to return to Leslie to help care for King’s mother. After the shooting, King turned the gun on himself and committed suicide…The St. Louis Community Center needed a director before and could not open its doors until it hired a part-time person to oversee activities for junior and senior high students…The St. Louis Rotary Club heard a report about a proposal to grow more evergreen trees and shrubs in St. Louis. Verne Miller of Alma brought samples to illustrate how these could help St. Louis…The Blue Star Mothers of Gratiot County continued their push to raise money and to establish a war memorial in Gratiot County. The group had more than 3,000 names for support and $5,500 so far for their project.

Rural teachers in the county had the opportunity to take college extension work this winter from Michigan State College. The classes were to take place in Ithaca…A March of Dimes Campaign took place in mid-January to help victims of poliomyelitis. The goal was to raise $3,200…The movie “Wilson” appeared for one day only at the Alma Strand Theatre. The new movie told the story of President Woodrow Wilson. The evening show cost $1.10 for adults, but a matinee only cost 76 cents…Income tax meetings for farmers took place in three places in Gratiot County. They were held to clarify the topics of dependents, deductions, and how to report sales of assets…A dairy specialist from Lansing came to Middleton to talk to farmers about ways to improve dairy production…St. Louis High School held a town hall speaker who was a survivor of a Japanese prisoner of war camp. United Press correspondent Robert Bellaire was held for six months outside of Tokyo just after Pearl Harbor. He was one of 45 prisoners who were part of a prisoner exchange in 1942…The Bridgeville School in Washington Township reported that twenty students were enrolled there, and the Christmas Seal Program raised $8.22, according to teacher Mrs. Mabel Biddinger…The Fulton E.V. Aid had a fish dinner that served 105 people and raised $48.10. A donation was made to the Infantile Paralysis Fund…The annual athletic banquet at Ithaca brought 225 people to listen to Albion College Athletic Director Dale Sprankle. After a chicken dinner, four Ithaca boys were recognized who would soon leave for the armed forces. Marvin Gabrion received the 1944 Most Valuable Player…The Alma College basketball team played a team made up of men from Fort Custer.

The St. Louis Commercial Savings Bank received recognition for its growth as a result of its reorganization and service since 1934. Vere Nunn, who had worked for the bank for over 35 years, now served only as its President…A group of 166 members of the Gratiot County Farm Bureau met at its annual meeting in Ithaca to hear Professor E.C. Prophet talk about “Geography in War”…Max Paine’s Fulton basketball team defeated Ithaca 34-21…The St. Louis GEM Theatre collected money for the March of Dimes program…A total of 70 Gratiot school districts received $45,265.74 in state aid. Alma city schools received $15,297.00 while North Shade No. 4 got $205.87…Forest Ervay purchased Duck Pin Alley in St. Louis. Four leagues had been formed and bowling took place four nights a week…An Adult Education program continued to grow at Alma Schools. Director Sylvia Williams was in charge of the program… and the Annual Week of Prayer, sponsored by the Ithaca Ministerial Association, took place.

And that was Gratiot County’s Finest Hour in January 1945.

Copyright 2020 James M Goodspeed