Above: Advertisements from the Alma Record and Gratiot County Herald during June 1918.

On the eve that many Gratiot County men went into combat in France life at home centered around showing how patriotic people were.

During early June 1918 twenty-five boys weeded beets on the farm of Arthur Gibbs, just east of Ithaca. Any farmer who wanted help on his farm only needed to contact L.A. Murdick, who was the county’s YMCA secretary. Murdick helped any farmers to locate young people as workers. The Crandall and Scott business in downtown Alma displayed a new show rug in its window. This “liberty rug” had images woven into it from all of the Allied Powers at war, as well as the Statue of Liberty, the Capitol, and Independence Hall. The rug was admired by many viewers. Miss Lou Florence Olp, a former Alma resident and one of Saginaw’s finest piano players, was headed to France to serve as a volunteer for the YMCA. A new call went out from the government warning “alien women enemies,” German women who were not legally citizens, to register at the Ithaca post office. This applied to women from the age of fourteen and older who were born in Germany had unnaturalized German parents, or who were Americans and had married an unnaturalized German. Two weeks after the announcement not one single person had registered – and there was no evidence that anyone in Gratiot County did in June. The Alma Red Cross had six sewing machines in operation but it needed more help to keep them going all of the time. Local post offices informed people who were sending weekly and monthly magazines to soldiers needed to only send current issues. Too many people were leaving old periodicals there that were of little value to soldiers. The Gratiot County Herald had service buttons for people in Ithaca who were family members of men in the service.

During June, the government urged everyone to buy War Savings Stamps. Everywhere in the county people were encouraged to “Paste the Kaiser with WSS (War Savings Stamps).” A new WSS saying could be heard: “Every quarter that you get, buy a stamp and make it wet, Stick it to a little card, it will hit the Kaiser hard.” Down at Middleton, Principal Miss Bertha Hoxie told the Gratiot County Herald that the school had students in Mrs. McCarthy’s room raised $190.00 in stamps and bonds. Miss Vera Martin’s class gave $750.00. Two other teachers and other students of the Middleton schools raised $1,475.00 for the war effort. President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation that June 28 would be National War Savings Day and that Michigan needed to raise its full quota of $70,000,000. Gratiot County’s new goal was to raise $497,200. Area ministers were asked to read a message from the President to their congregation explaining the need to support “The Big Drive.” Patriotic citizens needed to support the government by purchasing War Savings Stamps and Liberty Bonds by that date. Citizens also were urged to practice economy and thrift and not to spend their money thoughtlessly or needlessly, so that they could buy stamps and bonds. Advertisements in the newspapers reminded that all of those who purchased $4.17 worth of stamps each month could be redeem them for $5.00 on January 1, 1923. People were asked to “Prove Your Patriotism” and be a “True Blue Patriot” on June 28 and to step up and buy the stamps.

The fight over wasting and conserving food continued. Eating places like hotels and restaurants could not serve beef more than twice a week, one time each for beefsteak and roast beef. More pork could be available to supplement the meals, as well as beans, bacon, ham, and sausage. Michigan Governor Albert Sleeper endorsed the use of potato bread in place of wheat bread. Using Michigan potatoes demonstrated patriotism and support for the war, and Michigan still had much left over from its 1917 harvest. The use of “combination substitutes” was also promoted for different recipes for muffins which included either buckwheat, barley, or rolled oats. Women were told in advertisements that “Wheat Will Halt the German Drive” in June and everyone needed to pitch in. There was also a movement for “The War Garden Army” which hoped to enlist five million boys and girls and forty thousand teachers to help turn any vacant garden or back lot into a “War Garden” to produce more food that summer. By late June, at least 16 groups had formed in Gratiot County. People were also urged to raise chickens for food. Two to three hens for each person in a household would produce enough eggs for the family. Those who sold eggs at retail had to make sure that the eggs had been candled and boxes had to have candling certificates to prevent the selling of eggs that were unfit for consumption. Sugar was expected to be available to people for the next two to three months. However, the government planned that each person would consume no more than three-fourths of a pound per week. Those families who lived in town could obtain two pounds per week; those in the country were sold five pounds.

Increasing pressure was being placed on people throughout Gratiot County to demonstrate how patriotic they really were – even beyond buying bonds, donating money and conserving food. At the Ithaca Methodist Church, a crowd of 500 people came to hear about the atrocities committed by the Germans against Serbians and Belgians. Over $250.00 in donations and pledges were made to the American French-Serbian Field Hospital. Both Ithaca and Alma held a community “Patriotic Celebration” on the Fourth of July. At Ithaca’s Woodland Park, Ladies of the Eastern Star and the Gratiot County Guard Troop had an encampment which recreated a mock battle, held a marksmanship contest, played a baseball game, offered a band concert, and held a parade of patriotic floats. The public was asked to come and bring a picnic lunch (with enough food to also feed one soldier). Free ice cream and coffee was provided. Other things were also asked of Gratiot’s Citizens pertaining to their patriotism. On July 8, all school districts in the county would have a “Patriotic Meeting” at its schoolhouse. Schools and teachers were responsible to provide “a stirring patriotic rally” by opening with a prayer and singing “America” as part of its program. It was important to feature a local speaker, review why America was fighting the war, and tell why support for the war needed to continue until it was won. July 8 was chosen because it was the date of the annual school meeting in each school across the county. Finally, patriotism for the first time in Gratiot County was being measured by what people should not do. Rumors, false reports, and criticism of the government of any kind were discouraged. In a column in the Gratiot County Herald, the government even went so far as to state that “Any word which tends to create a doubt or a question in the mind of an American citizen as to the purity of purpose of the government is an act of treason.”

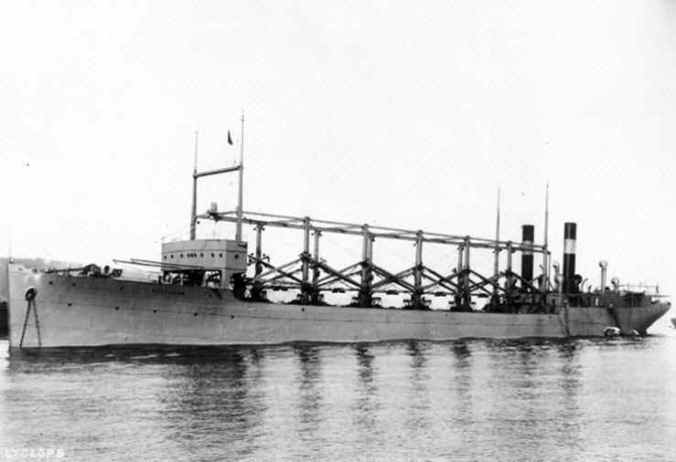

More and more men were being called into the service. At least 250 men in Gratiot County had turned 21 in the last year and were, therefore, eligible to be drafted. As the War Department made it a goal of having 3,000,000 men in the service by August 1, Michigan’s quota for the draft was 8,900 men. Draft boards now had a new pool of draftees: those who were in non-productive employment. Professional baseball players, sales clerks, clerical workers, traveling salesmen, public and private, cooks, managers, elevator operators, managers – all were now open to the draft. While a headline read that “Married Men are Exempt,” there were narrower definitions of who qualified for an exemption , based on when they married and when they had children (generally within the previous year and when a prior draft call had been announced). It seemed that each week the name of one man who entered the service was featured in the news. Vernon Pino of Ithaca received a send-off from the Home Guards, after having a farewell banquet and gift of a wristwatch. Reverend George Brown of the Breckenridge Congregational Church enlisted in the YMCA and was on his way to New York City. Brown expected to leave soon for France. L.T. Chapin, a businessman of the Fleming Clothing Company in Ithaca, left for the United States Merchant Marines Alma, it was noted that Nick Bardville, a recent manager at the European Café, was being a good example for service by his training at Waco, Texas. Bardville was not yet an American citizen, but he was eager to fight the Hun. Some Gratiot County men at Camp Custer were told that they may be sent to Italy.

Letters from men gave people different viewpoints about the war. Private Claude Eastman described to his mother some of his experiences as a sub chaser on the Delaware River in New Jersey. While he was not on board when any of the German U-boats were hit, he noted that Sub Chaser S-646 got one of them. Lester W. Pressley wrote somewhere in France about the value of the YMCA as a place to find reading materials and with help writing letters. The entertainment at the YMCA was also very good. Although he had to shop at different places in town, he was able to eventually find enough ingredients for French fried omelets, completed with fried potatoes and vegetables. His company was also in charge of maintaining its own garden. Pressley’s village was free of mud, but woe to those soldiers who marched in the valleys. Lyle Smith from Perrinton also wrote home to a family from his location in France. He wrote that he was recuperating from several days in a hospital due to a terrible episode of mumps. He was amazed that French farmers only used one horse at a time to work in the fields. There were a lot of goats and he even saw one woman with a small pig in a baby carriage. Smith’s letter seemed to describe the lighter side of military service “Over There.” However, before the end of summer, he would among the county’s first fatalities in France.

And Gratiot County continued on in the Great War in the summer of 1918.

Copyright 2018 James M Goodspeed