Above: A picture taken around 1918 of the students who attended the Lewis School in Newark Township. At least six of the children in the picture were relatives of the author. The girl in the second row, far left, is the author’s paternal grandmother. All of these students lived at the time of the Influenza Epidemic that raged through Gratiot County from 1918-1919.

The second and most massive wave of the Influenza Epidemic in Gratiot County claimed its first victim with Reverend F.E. Gainder. A Baptist minister in St. Louis, Gainder died in early October 1918. he had been sick since April; however, the St. Louis Leader stated that influenza and pneumonia took his life. Gainder was only 35 years old and had been a pastor in town for five years.

Possibly the last victim in Gratiot County lost their life in late May 1919. The Alma Record reported what appeared to be the last occurrence of influenza with the death of the Lane family of Alma. Harry Lane returned to Alma to bury his parents, who had both recently died. Then Lane returned to his home in the East. Unfortunately, Harry Lane contracted influenza, followed by pneumonia, and died. The Alma Record ran the headline, “Entire Family Wiped Out in a Few Weeks.”

Between these two stories, a swath of death and sickness took place in Gratiot County starting in October 1918 through the end of March 1919. A survey of newspapers during this period shows that at least 400 people became sick in Gratiot County, and at least 90 individuals died. However, these numbers are imperfect as these are only the sick and dead that can be identified. Also, the figures also do not include Gratiot County’s servicemen who died from influenza or pneumonia while serving during the World War. It is important to note that I tried to refrain from counting “neighboring communities” whose stories appeared in the newspapers. Places like Vestaburg, Carson City, Jasper Township, and the Wolford District were locations all adjoining Gratiot County, which frequently appeared in the county newspapers.

An important question to ask is how many people were sick or died who went unreported. During this time, obituaries rarely occurred in the newspapers, and this epidemic took place before funeral homes existed. Many who died during the epidemic were taken to an undertaker, then to the cemetery for a quick burial. In several cases, family members of the dead struggled to make it to the cemetery because they themselves were extremely sick.

There was little time between the passing of a loved one and burial, probably because of health reasons. For those of us today who are accustomed to funeral home visits, viewings, and church services, followed by interment at the cemetery, the process of death and burial was brief in 1918-1919 Gratiot County.

Another thought about Gratiot County is how it compared in scope with the State of Michigan during the epidemic. From October through December 1918, at least 25 percent of the state’s population was hit by influenza. During these months, 6742 people died from the flu, and another 7247 died of pneumonia. In 1917, a total of 427 people in Gratiot County died. A year later, that number rose to 488 deaths, an increase of 14 percent. These statistics do not include those who died in early 1919 from influenza and pneumonia, thus I believe that the number of at least 90 dead from the Influenza Epidemic is very possible.

Still, there are significant lessons from this event in Gratiot County’s history. One might ask, what exactly should Gratiot County learn from the Influenza Epidemic?

- During the time of the Influenza Epidemic, Gratiot County was rife with patriotism and support during the World War. There was no tolerance for any criticism of the government during this period. People were expected to buy War Bonds and support the war effort. Those who did not buy bonds, or who showed any reluctance in supporting the war found themselves identified in the newspaper, ostracized, and deemed un-American. One of the ways that people showed support for the war was through mass gatherings, parades, and attending speeches and rallies in the county. Attending meetings like these from September through November 1918 became fostering grounds for the spread of influenza once it arrived in the county.

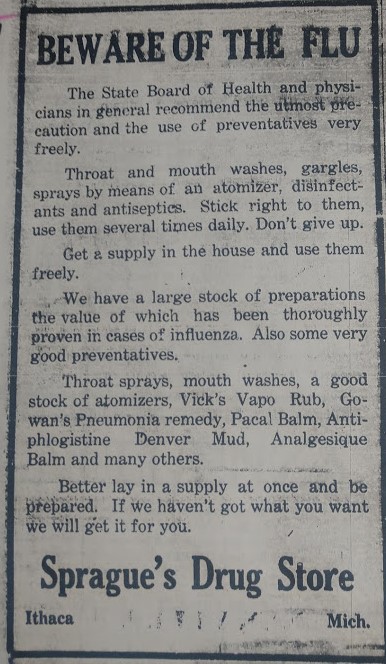

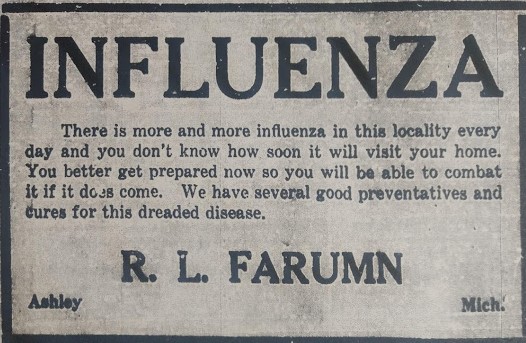

- The Influenza Epidemic that hit Gratiot County moved unevenly at times. Early in the second wave, surrounding villages and hamlets were stricken. Places like Perrinton, Middleton, Ashley, and Breckenridge paid dearly with the widespread flu. Larger towns like Alma and St. Louis also were hit, but not always at the same time. Ithaca boasted that “only two people” died of influenza by early December 1918, but was hit again by Christmas. When some communities thought that a wave had passed, places like Ithaca or Breckenridge would see flare-ups again.

- The chief weapon against the Influenza Epidemic was social distancing, a practice that went back to the Middle Ages. People did not have answers for how to overcome this strain of influenza – even though different remedies were tried. The best recourse people had was to quarantine themselves. When dealing with an unknown enemy, quarantine was the only answer Gratiot County’s doctors and health officers could recommend to survive the epidemic. Mask wearing also became a practice in public, whether at Alma College, in local churches or while conducting business in towns or villages. These quarantines tested businesses, churches, and schools, as well as those who could not stand to be in quarantine, or who did not believe that quarantines helped. Some places did try treatments in the form of public vaccinations in Alma and Ithaca by December 1918. To avoid wearing masks in public, people in Alma and Ithaca lined up to receive these shots (usually a set of three). One of the critical lessons from 1918-1919 is that people needed to listen to health experts. Some did, and some did not.

4. While looking at the death and disruption of the Influenza Epidemic, there is a need for a recognition of heroes and empathy for the times. Health officials had the toughest jobs during the epidemic of 1918-1919, if for no other reason than most doctors did not want the job. In Alma, Doctor Thomas Carney fought many battles with citizens regarding quarantines. Carney quickly learned that people who did not believe they were in danger would not obey the health officials. Some people bluntly asked if health officials had the right to enforce quarantines. The state said yes, but in many communities, people did not listen. While dealing with the epidemic, many Gratiot County doctors became exhausted while trying to help the sick and dying. Taking care of 40 to 60 people at a time (which happened in Breckenridge) must have worn these doctors out, but they continued to help the sick in their communities. We know that there were nurses involved, and at least one in Alma lost her life while helping the sick. The Red Cross chapters in Gratiot County mainly focused their efforts on providing an assortment of dressings, garments, and other things for the war and war relief, working out of their local rooms. It is not clear what effect they had in the county, but they continued to focus on their work and mission for those people in need in the military and in Europe. Gratiot County has many stories of individuals who helped others by leaving their homes to take care of relatives and loved ones. In different instances, people left Gratiot County and traveled distances to care for family and friends because no one else could help.

5. Finally, we have to recognize the issues of blame and shame that came about as a result of the epidemic. Who was to blame for the Influenza Epidemic? Where did this plague originate? Why was it here, and what could be done to survive it? These were questions that people privately asked amidst the losses that they suffered in 1918-1919. For those who lost family members, there was no easy answer to these questions. This generation lived with the shame that meant not talking about the epidemic and those who were lost. I believe that this issue of shame is the reason why many Americans never heard much about this epidemic.

For those who have followed this blog over the past few weeks, I felt it was important at this period of American history to tell the story of the Influenza Epidemic as it related to Gratiot County. I have spent the past two months of my own quarantine deliberately trying to finish a first run of writing about the research I started two years ago. During the summer of 2018, I spent three weeks at Virginia Tech working with a group of teachers in a National Endowment of the Humanities Seminar entitled “The Spanish Influenza of 1918.” My teacher was Dr. Thomas Ewing and we spent one of those weeks doing research at different places in Washington, D.C. Work in the Library of Congress was especially helpful in learning the story of influenza as it applied to Camp Custer in Battle Creek, Michigan. Records at the National Archives II in College Park, Maryland also helped to shed light on what happened at Camp Custer. Still, returning to Gratiot County’s newspapers enabled me to find the best examples of what happened where we live.

In 1988, I sat in a history class at Central Michigan University about the Roaring Twenties. Professor Calvin Enders required the reading of one book, Geoffrey Perrett’s America in the Twenties, which was then one of the more recent books written about that decade. One of Perrett’s first stories related to the end of World War I described the Influenza Epidemic in the United States in 1918-1919. I had never heard of this event, and I knew nothing of its history – even on what was then the 70th anniversary of the epidemic. Back then it was hard for me to understand why I had never heard of this chapter in our history.

It was also in the late 1980s that I lost my father’s parents, who had grown up as children during the World War I era. In all of my experiences of hearing my paternal grandmother talk about growing up in Newark Township, I never once heard her refer to the Influenza Epidemic. I later found out that Newark Township was hit hard – and that Myrtle Bliss had lost a sibling to disease just prior to the epidemic. Down the road from each other, two large families, named Bliss and Goodspeed, each with many children, grew up and lived during this time when the spectre came to Gratiot County.

And to my knowledge, none of my family and relatives ever talked about it.

Copyright 2020 James M Goodspeed

Above: Agnes Yutzey’s YMCA portrait; Yutzey’s application for a passport; staff picture from Ithaca Schools, taken prior to volunteering to work with the YMCA.

Above: Agnes Yutzey’s YMCA portrait; Yutzey’s application for a passport; staff picture from Ithaca Schools, taken prior to volunteering to work with the YMCA.