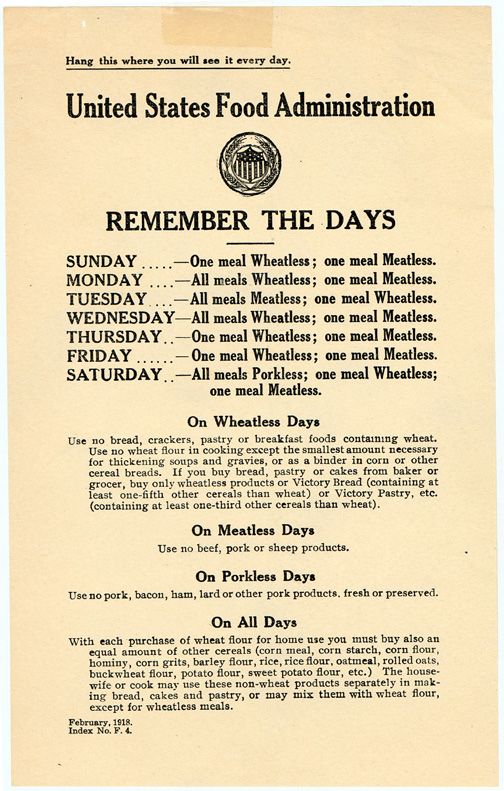

Above: Signs that would be found in Gratiot County homes that volunteered to conserve food during 1918 from the U.S. Food Administration Service.

As the war effort continued at the start of 1918, daily life across Gratiot County was filled with patriotism.

For the first time, Gratiot County residents learned how to file their first federal income tax. A federal tax officer announced that he would be in his newly opened office in Alma in order help people make out their returns. There was no charge for the service. Married persons with an income of over $2000 and individuals with net incomes of $1000 had to file this new tax form. An estimated 5000 people in the county would have to file their taxes for this first time in history. Penalties for not doing so ranged from $20 to $1000 or going to jail.

St.Mary’s Church in Alma displayed a new service flag which had twelve stars, one for each member of the church that was currently in the service. One of the stars was for Father John Mulvey and another four represented four Alma College students. Alma College also hosted one of the first patriotic “pep rallies” in the county that would take place throughout 1918. More than one of these that year involved a speaker or serviceman from Canada or England. Doctor George Robert Parkin, from London, England, who was the Director of the Rhodes Scholarship Trust, spoke to an audience in the college chapel. He expounded on how the United States and England were partners in the world war and they alone were left to win it since Russia had fallen into civil war and France was on the verge of collapse. Parkin also admitted that he was in the United States in order to assess the attitude of Americans toward the war. The Ithaca National Bank, “The Bank on the Corner,” encouraged people to purchase War Savings Certificates, also called “Baby War Bonds. The Alma State Bank stated that it sold $700 worth of stamps to customers there.

Probably one of the biggest things that affected the daily lives of Gratiot County residents involved what became known as “The Prudden Orders” (named after W.K. Prudden, the Federal Fuel Administrator). These orders dealt with how the state of Michigan would conserve fuel for the war effort. Regulations were issued about how long certain buildings could be heated or lighted each week. Stores could only operate for nine consecutive hours a day, except for Saturdays when they could be open for twelve hours. They also faced regulations on how many hours they could be lighted outside. Inside, the heat was set to no more than 68 degrees. Movie theaters in the county were closed on Tuesdays, on other days they were limited to six hours of operation. Saloons and bars were closed on Mondays. Meat markets and grocery stores could only be open until noon. It seemed that everywhere the public was now called upon to make fuel sacrifices because of the war.

And then there were new issues with food. By late January, families had to apply for government-issued sugar cards in order to purchase any sugar in grocery stores. Ration cards were sent to each family to cover three months, with a grocer allowed to sell them only one pound of sugar per week. The card was punched by the grocer with each purchase. The government warned that there was not enough sugar in the country for everyone to have the usual amount until the fall harvest. It was suggested that children be given syrup, honey, molasses or preserves for snacks, as well as raisins for dessert. Mothers were encouraged to make a cake without frosting and to encourage the eating of preserves. Coffee drinkers were urged to go easier on sugar in their coffee – and never leave any in the bottom of the cup. It was hoped that people in Gratiot County would limit themselves to no more than two ounces of sugar per day. County newspapers would continue to publish columns such as “WE WON’T WIN IF WE WASTE: Tested Wartime Recipes.” Examples included recipes for how to make Soldiers’ Mince Pie, Liquid Yeast, Old Glory Bread, Oatmeal Muffins, and Bread.

The county moved to a voluntary “porkless Saturday” at the end of January. The pressure was put on families to voluntarily comply with this idea with the threat that eventually “porkless days” could become mandatory. The Gratiot County Herald issued a note from C.J. Chambers, the Food Administrator for Gratiot County, who admonished readers that “OUR GREATEST PROBLEM IS ONE OF FOOD!” He then asked them directly whether or not they observed meatless Tuesdays, wheatless Wednesdays, and having one other meatless meal at least once during the week. The article went on, “We are at war. Our soldiers and sailors come first. There should be no hoarding of flour or sugar in Gratiot County…You cannot afford to assist the enemy by deliberately refusing to observe the food regulations. If you do, you are only pushing victory away that much longer. Let’s Hooverize Gratiot county 100%.”

Red Cross members continued to labor faithfully across the county. In Breckenridge, the branch there met twenty-four afternoons since it formed the previous July. Although meetings only averaged about ten ladies, the group had expended a total of $278.68 on material and focused on creating surgical dressings. Other small Red Cross branches continued to serve. The East Fulton Red Cross had sixty-two members, held twenty-five meetings and had an average attendance of seven. With fuel shortages taking place the group held their meetings in the homes of members. They produced T. bandages, pillow cases, nightingales, and abdominal bandages. The Newark Red Cross, led by Belle Kellogg, met at the Grange Hall where twenty-three women came in one day to work. After citing their accomplishments for the month, the group remarked that “The truly Red Cross spirit means our love for humanity and the work we do is measured by this love.” Camps at Fort Wayne, Selfridge Field, and Camp Custer received the many different things created by all of these Gratiot County women.

As the draft continued so did problems with those men who failed to heed the call. Those who did not report for the draft had their names turned over to the police. Early in the month, fifty-eight men failed to return their questionnaire and their names were published in the newspapers. The local draft board also thought that many of the men who registered did not understand the correct methods of classification, whether it was due to physical conditions, or because they claimed agricultural and industrial work grounds. Because of these problems, the draft board had to again examine 2,600 papers and then call men back in again to answer questions. Men who had married since May 18, 1917, had to furnish proof to the draft board that they had not gotten married just to avoid the draft. A special drive was taking place with the Alma enlistment office because it wanted to enlist a total of forty men for the month of January. If the county did this for a second consecutive month, it would be classified as a central recruiting office, one which would have been uncommon for a county population under 50,000 people (which Gratiot County did not have in 1918). When enlistments lagged at mid-month due to a winter storm, officers went to Breckenridge and Shepherd to drum up recruiting there. Unfortunately, the drive failed. The Army also put out a statewide announcement that 7,000 specialists were needed for the Aviation Section Signal Corps which was stationed Camp Hancock, Georgia.

` Gratiot County’s soldiers continued to write or visit home. Lieutenant Charles Dutt came home to Alma on his last leave from Mississippi, his last before being sent to France. Howard Burchard was also home on furlough. He had served as a gunner on the S.S. Teresa, a merchant ship that had been attacked one night by torpedoes off the European coast. Luckily, both shots missed the ship. Lester N. Pressley wrote home from “Somewhere in France.” He said that the climate was fair, he had candles with which to read and write at night, and he valued the handkerchiefs and hats that the Red Cross was knitting and sending overseas. Ted Kress from Ithaca wrote home that he and a group of men had purchased a type of phonograph that they hoped to take with them to France. Herman Rahn, who was with the Field Hospital Company Number 127 at Waco, Texas, explained how he had to try out newly created gas masks. Clyde E. Marvin, also stationed at Waco, wrote about the cleanliness and order at the camp. Napoleon Vancore published a column from Camp Custer and had his picture published in the Alma Record.

Finally, there was the growing reality that the war was going to reach more men and women from Gratiot County in 1918. Alma College faculty prepared to teach a new course about how science applied to warfare. Subjects included: gas masks, diet, frostbite, how to purify water and how to use the stars for direction. Conversational French was also being offered. The college announced that it was going to cancel spring break because students were going to be called for the draft or sent to farms to work in the spring. Telegraphers were also needed by the Army Signal Corps. A new war disease was named that affected soldiers on the Western Front. It was called “trench foot,” which was the result of standing in cold water both day and night. In many places in the county’s pool rooms, train depots and post offices posters told men of the trades that the Army offered for those who enlisted and how many men were wanted for service.

The year 1918 was starting and it was going to be an interesting one for Gratiot County’s involvement in the Great War.

Copyright 2018 by James M Goodspeed