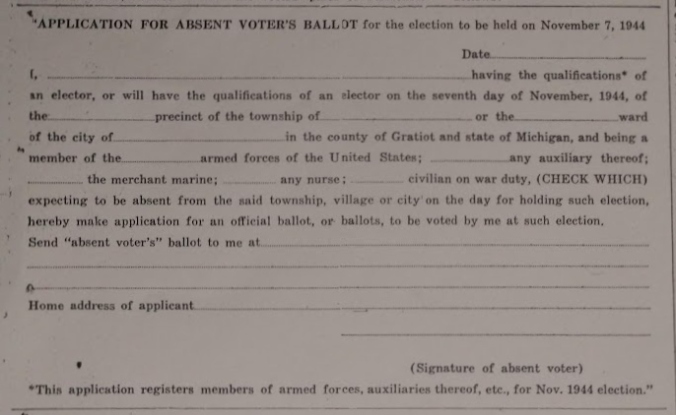

Above: “Japanese Sandman” from August 24, 1944 issue of Gratiot County Herald; the Wymer Brothers were representative of several Gratiot County families who sent several sons (and daughters) off to war; Absent voters ballot sent to Gratiot County men and women let them vote in the 1944 elections; Rationing notice from Alma Record, August 3, 1944.

People called it “Victory fever.” Many used the phrase, “End the War in ’44.” Still, others would talk of the idea of having the soldiers who were in Europe home for Christmas. Gratiot County, like many other places in the United States in August 1944, followed the news of Allied armies as they moved across France after D-Day. It seemed that Americans would soon be knocking on the door of Hitler’s Germany.

Similar to the war fever that ran through Gratiot County in the late summer of 1918, Americans began to think that the war in Europe would soon end. Some cities and towns even started to discuss plans for “Victory Day.” However, in reality, the war would not stop as quickly- or as soon- as Americans hoped. As the liberation of Paris approached, a new brand of “Victory fever” was running wild in Gratiot County in August of 1944.

Rationing Continues

Taking care of gas and tires remained rationing problems. In September, a new “A” gas rationing book would be issued to people for three days through the public schools. The current gas books expired on September 21 and teachers and administrators oversaw the distribution of new ration books. Tires were another issue. While the Office of Price Administration cut the number of available casings, it increased the number of heavy truck and bus tires that people could obtain. Last winter’s supply of passenger car tires was gone. If anyone applied for new tires, they had to have their old tires inspected and provide evidence of prior inspections.

Every 5,000 miles, or every six months, owners were expected to have their tires inspected. During one week in mid-August, the county rationing board gave out tire certificates for 150 grade 1 tires, 24 grade 3 tires, 20 small truck tires, 4 small implement tires, and 1 large implement tire. To educate people in the county about the importance of conserving rubber, Lamerson’s Shoe Store in Alma put up a window display. In showed a five-person rubber raft, a rubber diving suit, flying boots, and a pair of Alaskan Mukluks. The display emphasized the importance, conservation, and preservation of rubber.

Other items to be rationed in August included waste paper and rags. In late August, Ithaca held a paper collection, courtesy of Boy Scout Troop Number 113. Anyone in Ithaca who had items to donate needed to tie their paper up into bundles, or place it in cartons. A “Salvage” sign had to appear in the windows of those wanting pick up. A similar drive took place in Alma, and the Boy Scouts picked up paper items, as well as tin.

Food was another essential item to be rationed. Sugar Stamp 33 remained good for five pounds of sugar starting in September. However, Sugar Stamp 40 was to be used for home canning and remained good until February 1945. Canned corn went back on the ration list and cost three ration points for a twelve-ounce can. In good news, grape jam came off the list and was ration free because of an oversupply that lasted the remainder of 1944. If you lived in Alma, you could enter into a Victory Garden contest. E.L. Mutchler, who served as the Alma Victory Garden campaign manager, offered a prize of $10 for the best garden. Second place would win $5. Anyone interested in entering the contest needed to send him a postcard with the address of their Victory Garden.

War Bonds Results

Results of the Fifth War Loan Sales in July appeared in the newspapers. Gratiot County raised a total of $1,400,742.50 in bond sales. While individual sales were down, corporate purchases went up. Results from rural areas in the county had Emerson Township leading the way with $22,450 in sales. New Haven Township bought $5,250 worth of bonds. The government also announced that another War Fund Campaign would start in October to finance the work of the USO and other war-related agencies. The goal was to raise just over $5,000,000.

The Red Cross

As more talk took place concerning the end of the war, the Red Cross was asked to help with issues facing American servicemen and women who returned home. In early August, a group of over 40 Red Cross workers met at the St. Louis Park Hotel. They listened to the head of the Michigan Veterans Administration talk about how to assist these veterans when they returned to Gratiot County. The St. Louis Red Cross Chapter also proclaimed that it met its quota of making 19,000 4×4 dressings that summer. The chapter then celebrated their accomplishments by having dinner in the city park. To accomplish their feat, the St. Louis women continued to out of the back end of the St. Louis Leader’s office.

Gratiot’s Men and Women in the Service

The only men who left Gratiot County through Selective Service in August consisted of a group of 13 men who departed July 27. Some in the group included Durwood Moon from Ithaca, John W. Morrison from Middleton, and John J. Koval of Alma.

In late August, the Gratiot County Herald featured the stories of the Wymer Brothers: Cutha, Virgil, Lois, Wallace, and Ora. Cutha and Virgil were in the Army; the other brothers all served in the Navy. Ora joined the Navy in April at the age of 17, and one brother remained at home. Another Gratiot County family, the Tomaseks from Bannister, sent their sons and daughter off to war. Brothers August and John, both in the Army, met each other during the drive on Rome, Italy during the summer. They had been in Europe since early 1942. Brother Steve Tomasek, a recent Ashley High School graduate, entered the Army on July 7 and was sent to Camp Hood, Texas. A sister, Lieutenant Caroline Tomasek joined the Army Nurses Corps in February 1943. She graduated from St. Mary’s Nursing School in Saginaw and was somewhere in Europe.

News came from around the United States and the world about what was happening to Gratiot’s men and women who went to war. Sergeant Marvin Mates of Breckenridge received an Oak Leaf Cluster for flying aboard a B-24 between Vienna and Bucharest. Mates was a ball gunner. Private Quentin Greening from Breckenridge graduated from the Department of the Armament in Colorado. He was trained to help with the maintenance and operation of heavy bombers and fighter planes. Lieutenant George Townsend from Alma completed his 60th bombing mission as a B-26 Marauder pilot. Townsend was a part of “Nye’s Annihilators” which helped support Allied ground troops in France.

Staff Sergeant Robert Bebow of St. Louis had seen action in many places since Pearl Harbor. He joined a Flying Fortress unit and was in the first attacks over Nazi Germany in the fall of 1942. Bebow also gained recognition as one of the best radio maintenance mechanics in his squadron. Gene Hetzman from Alma was in aviation school in San Antonio, Texas. Corporal Lyle Hynes of Wheeler was stationed in Northern Ireland and served as an engineer on medium bombers. He had been at his location since July. Major Selby Calkins, an Alma High School graduate, had participated in B-29 raids on July 29 over Mukden, Manchuria. Calkins was squadron leader in the 20th Bomber Command. Lieutenant Lewis Jolls, who formerly worked for the Gratiot County Herald, came home from England after flying 30 missions as a pilot on a B-17 over Germany. He flew over Berlin as recently as June 21.

At Fort Benning, Georgia, Francis Stearns of Alma graduated from parachute rigging and packing school. He was one of those men who had the critical job of preparing and maintaining parachutes for paratroopers. Lieutenant L.D. Huffman of Alma announced that he had been given membership in the “I Bombed Japan” club. Huffman was in the 11th Army Air Force and had bombed Japanese positions in the Kurile Islands. He had been in that unit for the past eighteen months.

Emery Bebow served as a seaman-cook and came home to St. Louis on furlough. Bebow had served for six months aboard the USS St. Louis. Private Wallace Humphrey of Elwell was in the United States Marine Corps and fought on Saipan and Tinian. Humphrey suffered no injuries during the fighting, even though he spent several days and nights in the rain without rest or hot food. Ensign Richard Terwilliger, Jr. from St. Louis became a lieutenant and served at the Naval Research Laboratory in Anacostia, D.C. He had graduated from the University of Michigan’s College of Engineering and went into active service as soon as he graduated in 1943. Private Howard Anderson of Alma came home after 29 ½ months in the Southwest Pacific Theater. Anderson received a well-deserved furlough. Harold Klein of Ithaca also came back to visit his family, along with his wife. Klein had been in the Pacific for the past eighteen months. Second Lieutenant Robert Jackson, who was from Saginaw and an Alma College graduate, was sent to Parris Island for basic training in the United States Marine Corps.

Technician Glen Shirey of Alma also came home after 26 months in the Southwest Pacific theater. He had been in the chemical warfare branch of the Army. Shirey’s father worked for Crippen Manufacturing. Harold Davis of Riverdale was preparing for amphibious warfare in the Pacific aboard LST landing ships with the Navy. The Executive Officer of Alma College’s V-12 Program, Lieutenant A.B. May, was called for service and was to be sent to San Francisco before heading for the South Pacific. May had been at Alma College in his position since the V-12 Program started in June 1943. Lieutenant Orville Dahl, from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, replaced him at Alma College.

In the Army, Warrant Officer Charles Letson from Alma was a part of 122 men sent to England in June 1942 to set up the largest supply center outside of the United States. Letson witnessed the depot grow as supplies went to fighter and bomber bases all over England. Sergeant Robert Campbell of Alma had been in Egypt and now was transferred to England. Corporal Bryant Betts of Alma reported to his parents that he had been “slightly injured in action.” He was serving in New Guinea and had been there since February. His brother, Zane Betts, enlisted in June 1943 while still a student at Alma High School. Zane Betts was also in New Guinea in the Navy. Private Leland Perry sent souvenirs from his experiences in Italy to his parents in Alma. These items included medals and badges he had been awarded in Africa and the actual pair of socks Perry wore when he marched through Rome when it was liberated. He also sent home a passkey from a hotel in Rome.

Sergeant Robert Bennett of Ithaca surprised his parents upon arriving home from Alaska on a 21-day furlough. Unfortunately, he could not visit with his sister and her family because they had gone away to work in the cherry orchards. A photo of Sergeant Harlan Stahl appeared in the Gratiot County Herald. Stahl was “somewhere in Russia” on assignment helping the Russians fight the war from the Eastern Front. More news coverage described the meeting of brothers Robert and Howard Comstock in England. The two had not seen each other in three years. Robert was serving in the Ninth Service Command trucking company; Howard was a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne. A picture of the two men together appeared in the St. Louis Leader Press. Private First Class Johnny Crispin of Alma sent word to his parents that the younger Crispin was within fifteen miles of Alma friends who were stationed in Italy. Among these friends included Private Bill Lippert, Private Louis DeRosia, and Sergeant Lyle Potter. When all four men were in North Africa earlier in the war, they managed to be within a short distance of each other for four weeks. Sergeant Leland Mecomber of Wheeler had his picture in the paper. Mecomber was responsible for refueling aircraft for the Twelfth Air Force B-25 Bombardment Squadron.

Then there were women from Gratiot County who also served in the Armed Forces. Lieutenant Penelope Sawkins came home to Alma on leave before being sent to Army Airways Communications system at Grenier Field in Manchester, New Hampshire. Sawkins had previously served for two years with the Army Air Forces in Washington, D.C. Another volunteer, Ruth Posey of Breckenridge, enlisted in the WAVES and reported to Hunter College in the Bronx, New York, to start her training. Lieutenant Margaret Langdon, a Carson City High School graduate, served as an air evacuation nurse in England. Langdon was frequently the only medical attendant on duty when wounded men arrived at her location. In some cases, she stated that flights taking supplies into France were quickly unloaded and then loaded again with wounded Americans arriving at her base. Miss Edith Dines of St. Louis enlisted in the WAVES on her twentieth birthday. The Alma Record noted that Dines was the first woman from St. Louis to join during the war.

Letters Home Tell of both Good and Bad

While families waited for word from a family member, the news could be comforting, humorous, or tragic.

Corporal John Brzak of Ashley continued to write letters to his sister after he had been wounded in the South Pacific. After being hit by Japanese mortar shells, Brzak was in a hospital where he received the Purple Heart. Brzak said that he had shrapnel removed and bayonet wounds stitched. “Well, Sis, I received your letter,” Brzak wrote. “The Nurse read it to me. I’m still on my back in a nice white bed and it sure does seem good to have a nurse around you all the time…I feel fine aside outside of my pains. Yes, I also get the Gratiot County Herald and does it ever bring memories back up here…” he concluded. Ted Osborne of Riverdale wrote from Italy to his two grandparents that he had not seen in two years. “It’s been two years since I’ve seen you…Personally I’m getting damn tired of this war business.” He told his grandmother not to worry about any drinking or smoking. “(I) Can’t do it and last long at this game.” He wrote that he marveled about the olives and grapes that the Italians were raising for wine.

The family of Private Dale Phelps, who lived in Riverdale, heard that Dale had received as many as ten letters. “That made me feel pretty good, although there wasn’t one in the ten from you (Mom and Dad). I suppose there is one on the way, isn’t there?” Phelps had acquired several Japanese souvenirs (including money, pens and a gun) and planned on sending them home. “Pep talk” letters sometimes found their way back to Gratiot County. Myron Humphrey sent such a one to his parents, asking them not to worry or cry about his safety. “Just say to (yourselves), there’s a job to be done and my son is in there helping to do it’.” Humphrey ended his letter with this assertion: “Did you ever stop to realize what would happen if the (Japanese) ever licked America? We would live in slavery the rest of our lives, and I don’t want my children being brought up to worship some guy on a white horse.”

Clarence Isles, who recently fought on Saipan, joked about his condition. He had heard American bands, attended a church service late one night, and even saw a show. “I hadn’t seen a civilian in so long that I almost forgot what they looked like.” He went on, “You should see me in the Pacific ocean, bare naked washing clothes. I sure wish I had a little portable washing machine.” After walking through mountains on sweltering days, he other buddies came back on an ox cart, filled with cocoanuts and bananas. “I am just a few hundred miles from Tokyo and 10,000 miles from home.” He closed, “I have sat in a fox hole and read letters from home with bullets and shells whistling all around me.”

A couple of St. Louis paratroopers also sent mail home. Private Fred Hicks in the 82nd Airborne commented about his diet in England. He wrote, “I’ll bet you’ll be surprised to hear that I have been eating some hot cereals. They aren’t bad at all, but I still like the cold ones. I am looking forward to a package from you folks because one does get hungry around ten or eleven at night.” Of particular value to Hicks was the presence of the Red Cross; they offered coffee and doughnuts each night. The Red Cross also welcomed Hicks and his fellow paratroopers with doughnuts when they first arrived in England.

For Howard Comstock, another 82nd Paratrooper, his letter home told about meeting his older brother, Wayne. It was the first time in two years that the brothers had seen each other, and it was very emotional. Howard described what it was like to see a brother who was nine years older and who seemed to acknowledge that the younger Comstock had grown up during wartime. When Howard found his brother’s unit in Oxford, he contacted the commanding officer for permission to see his brother, which was granted. To Howard, the meeting did not seem real until “it suddenly dawned on me that I was actually going to see my brother in a few minutes. Strange as it may seem, I got scared, stage fright, or something.” When the elder Comstock came down the hallway the first time, Howard did not initially recognize him. But, when Wayne came back toward him, Howard would write, “Oh, Gosh! What a moment that was. We didn’t quite break down and bawl, but neither of us could talk for a few minutes. I’ll bet everyone wondered what was going on for a minute – two soldiers meeting in the middle of a room, grabbing each other and then reaching for their handkerchiefs. Golly, but you’ve no idea how wonderful it was to see him.” Over the next three days, the two brothers proved to be inseparable. Once they even switched clothes and tried to pass themselves off as the other when around Wayne’s unit. They had a few laughs doing so. Howard’s assessment of the reunion concluded in the letter: “Wayne used me a lot different than he ever did before. He actually treated me as if I were grown up. Something new for him, wasn’t it?”

Those Wounded, Killed, Missing in Action, and Prisoners of War

There was no end in sight to Gratiot County’s casualties, and the numbers kept climbing as the war went on through 1944. Two months after D-Day, the continual Allied movement across France led to more losses. The same happened on islands in the Pacific.

Two Wheeler boys, Gordon Batchelder, and Lester Robbins were both wounded and placed in English hospitals. More information came in on Batchelder, who went to France with the D-Day Invasion and was injured on July 18. His last letters home to his mother described how he wrote to her while lying on his back. An Alma boy, Private Lester Tanner, Jr., was wounded in France on July 3. Private Richard Lover of Bannister was also wounded on July 20 in France. His Colonel wrote to the family and commended Lover for his service. Private Leonard LaBaron of Alma was wounded somewhere in France; he had received the Purple Heart and was back at duty. Private Anson Foster of St. Louis was wounded in Italy and sent his Purple Heart home to his wife. Foster was back serving in the Infantry.

Out in the Pacific, Ray Willert, who was a Marine, was sent to San Francisco after receiving severe injuries during fighting there. Willert’s brother was Alma Police Chief Earl Willert. Junior Rockefellow of Alma was sent to Percy Jones Hospital in Battle Creek after receiving wounds in Italy. Rockefellow had a foot amputated due to gangrene. He also had surgery for shrapnel wounds in his thighs. Corporal Matthew Mikula of Elwell participated in D-Day and was wounded June 18. Because of his injuries, he was sent to Crile General Hospital in Parma Heights, Ohio. He received the Purple Heart. Private William Dean of St. Louis was also wounded twice on Saipan and was in a Naval hospital. He was entitled to a Gold Star. Jesse Hanford of Alma had been hit in the foot by a Japanese sniper while in New Guinea. He was in a hospital there. The names of more wounded Gratiot men kept coming. Private George Kipp, Jr. (Wheeler), Corporal Eugene Randall (Breckenridge), Donald Randall (Breckenridge), and Private Leslie Tanner, Jr. (Alma), were all wounded in Europe and were either in English or French hospitals.

Hard news came to families in Gratiot County with the announcement of those who died. The family of James Kalahar of St. Louis learned that the 23-year-old bomber was killed during the invasion of France. He had been in Europe for about seven months. Sergeant Donald Wood of St. Louis also died in France while serving in the infantry. Wood’s wife also learned that two of her cousins were actually in the same battle as Wood and they had been wounded. Donald Wood was a graduate of Breckenridge High School. Private Stuart Brown of Alma died in France on August 11. He had only been in France for six weeks before being killed. Brown served as a driver in the wire section of his infantry’s communication division. He was married in 1942 and entered the service that same year. The parents of Lieutenant Howard Barton of Breckenridge received definitive word that their son was killed May 23 in action over England. A 1938 Breckenridge High School graduate, Barton also attended Central Michigan Teachers College in Mt. Pleasant. John Prout, Jr., whose father operated the High Speed Gas Station in Ithaca, was killed May 29. However, details about his death were unclear.

Those missing in action and who were captured as prisoners of war also were in the news. Staff Sergeant Dean Button of Alma had been reported missing in a combat mission over the Ploesti Oilfields in Romania. William Jordan of Ithaca and had been missing since February 15, 1943. His family received his Purple Heart. Jordan was a Seaman First Class in the Merchant Marines. The War Department added the names of Private William McGill of Alma and Sergeant Benny Zamarron of Ashley to an official list of prisoners of war in Germany. Sergeant Harold Waldron of Breckenridge had his picture appear in the Gratiot County Herald. Waldron became a prisoner of war in Germany on April 13, 1944.

Farmers and Farms in July 1944

The weather had been rough on crops in the county during July. Arid conditions meant that farmers hoped that more rain would fall. Some rain fell in mid-July, but only in scattered areas of Gratiot County. The extreme heat and high winds took off blossoms of beans; corn leaves were turning a brittle brown color. It seemed that all of the summer rain was hitting Michigan north of the Bay City to Muskegon line. Sugar beets seemed to be holding their own, and with more acreage planted in 1944 than ever before, hopes were high for a record harvest. One of the fears of the lack of corn available to feed animals in the county was that farmers would use new oats, wheat, and barley for their livestock. Farmers were urged to use their oldest grains first because the animals could become sick from eating recently harvested grains.

When it came to farming help, the State of Michigan School Superintendent, Eugene B. Elliott, urged high school students to return to school in the fall. During the war, an estimated 150,000 high school age students left school to work on the farms. Elliott stated that two out of every five youths were no longer in school. On the other hand, migrant workers left Gratiot County to follow the crops north. As planting, thinning, and blocking of crops had passed. Farmers were told that migrant help would return for the harvest season.

When it came to 4-H members in Gratiot County, a total of 38 young farmers raised beef cattle. They had 40 steers and eleven heifers or cows in their projects. Among these included Leo Goodyear and Earl Graham of St. Louis. Both raised Herefords.

The AAA told farmers that milk and cream payment checks would not be made until September. The payments would take place every two months after that, until March 1945. Gratiot County received a total of $56,831.74 in cash for July. On a side note, farmers were told not to wait until they ran out of gasoline before requesting more for farm work in July.

And So That We Do Not Forget

Egg breaking at Swift and Company in Alma had ceased. A group of 120 women had been employed there and were not needed…Tin and paper was needed for the war effort. Please help out…A county-wide milkweed pod drive was about to take place. Area school students were expected to help scour the county for milkweed, which was needed to replace Kapok for life vests for pilots and crew members…Citizens who still owed taxes from 1932 had to pay their next installment for the moratorium program…Saginaw was already planning for Victory in Europe day celebration…Corporal Harland Burton shot off his finger while hunting crows on his father’s farm near Alma…A new administration building was going up at the Leonard Refineries. The president and vice-president’s office would be in the west wing. All offices had asphalt tile floors, plastered walls and woodwork. Architect William Edward Kapp of Detroit designed the building… Sergeant Russell Shaw from Los Angeles, California, a renowned soldier evangelist, was holding meetings at the Alma Church of God. He had fought the Japanese in the Pacific, was seriously injured, and was honorably discharged…All Christmas parcels being sent overseas had to be labeled as such and not weigh more than five pounds…When 30 million school children invest fifty cents each, the result is paying for 33,100 jeeps that have come off of the Willys-Overland assembly lines…Absent voter ballots for 247 Gratiot County members of the armed forces were mailed out at the end of August for 1944 elections. They voted on paper ballots, just like everyone else in the county…Michigan had 124 cases of polio in 1944, 117 of them occurring since July 1. There had been two deaths…W.L. “Doc” Hetzman from Detroit was in the news. Hetzman, a native of Breckenridge, served as War Food Production consultant for Detroit and surrounding areas. Hetzman had an office on Woodward Avenue and his job was to oversee and encourage the use of Victory Gardens. Hetzman taught at Riverview School system for the last 16 years…Free movies started in mid-August on Saturday evenings in Middleton. They were expected to run every Saturday night for the next few weeks…The Ashley Methodist Church was the location of a patriotic wedding for Miss Evelyn Whitaker and Quentin Coon, who served in the U.S. Army Air Force. Thirty five people attended the wedding… Company C of the Michigan State Troops left the area for chemical warfare training northwest of Midland. Between 250-300 men from companies around mid-Michigan took the training…A display of the Lockheed Ventura sub-buster could be seen at First State Bank in Alma. The Ventura was built to keep America’s coast free from German submarines…Adele Cavanaugh of St. Louis continued to write a column to encourage St. Louis area youth who had left to defend the county at a time of war. Cavanaugh kept the public aware of the names of those who had left and the sacrifice they were making for St. Louis…And Private Walter Hartig of Alma, who was in somewhere in the Pacific, wrote a poem home to his father, Louis Hartig. It read:

“Dad, remember me, I’m your son.

I joined the Army to shoulder a gun.

I’ve done K.P., I’ve marched, I’ve drilled.

Went on bivouacs, learned how to kill.

Now I’ll do my job, we’ll win this war

Democracy is tops, that’s what we’re fighting for.

So you run the farm, don’t fret and stew.

I’ll be home when our job is through.

So long for now, Love –your son, Walt.”

And that was August 1944 during Gratiot County’s Finest Hour.

Copyright 2019 James M. Goodspeed