From top photo: The Klein Brothers from Ithaca went off to war to defend Gratiot County and the nation; headlines from May 17, 1945 as Major T.S. Nurnberger of St. Louis writes home about seeing Buchenwald; Tony Kuna of Alma was one of several Gratiot County liberators. Kuna was at Gunskirchen Lager in Austria; a shot taken in Ohrdruf, the first image to appear in Gratiot County which showed evidence of the Nazi genocide.

It is challenging to describe Gratiot County’s connection to the Holocaust in the 1930s and World War II. In a sense, it would be easy to say that most citizens in Gratiot County knew much about the persecution and murder of the Jews and other groups. However, Gratiot County did little to help. One can only imagine how perplexing it was for those Jewish families in the county to hear and learn about what was happening in European countries that Hitler and the Nazis overran during this time. As these citizens read, listened, and learned about the Holocaust, Gratiot County mainly watched, like too much of America during that time.

The Depression and the Start of War, 1934-1941

The Alma Record and Alma Journal first published a photograph of Adolf Hitler about his rise to power in Germany on July 5, 1934. This picture showed Hitler’s first meeting with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in Venice, Italy.

A few Gratiot residents had some contact with Nazi Germany during the decade leading up to Pearl Harbor. One of the first to meet Germans who were sympathetic to the new government in Germany was Howard A. Potter, his wife, and Barker Brown, all of whom were originally from Ithaca. The trio belonged to a group of Harvard students who partook in a German Christmas at Cambridge University. While attending the party in a church basement, a larger group of American students entered the festively decorated room and met the German Consul Von Tippelskirch. The Potters were shocked when the table they were assigned had a flag next to it that featured a large red swastika. Fortunately, the students were comforted when they saw an American flag on a nearby stand. During that visit, the Potters and Brown quickly became engaged in conversation to try out their English and German speaking skills, as did other students at the party. After socializing and eating, the students pushed back the tables, and many in the group danced to the music. Ultimately, the Potters and Brown were all impressed by the cordial German atmosphere at the Christmas party.

Almost one year before World War II started, Margaret Randels, originally from Alma, studied for one month in Freiburg, Germany. At the end of their journey, she and another student, Mae Nelson of St. Louis, came home from Europe aboard the SS Deutschland after spending part of their summer touring Holland. Neither Randels nor Brown commented in the newspaper regarding their thoughts about Nazi Germany after they came home.

By 1936, Hitler made plans and reoccupied the Rhineland, a direct violation of the Versailles Treaty, ending World War I. This action was Hitler’s first aggression leading to the start of the war. The front page of the March 19, 1936, Alma Record and Alma Journal issue showed photographs before Hitler prepared to occupy the Rhineland. As a result, discussions about the Nazis became more newsworthy in Gratiot County. As a result of Hitler’s actions, there was a new interest in what was happening with the Nazis. In October of that year, Dr. Theodore Schreiber, a German professor at Alma College, was called upon to share his knowledge of modern Germany with interested groups. In one case, Dr. Schreiber spoke to a meeting of 120 in a women’s group in Saginaw about what he knew regarding the history of Nazi Germany.

As the 1930s went on and the Nazis continued to take parts of Europe, the plight of refugees became an issue. The only evidence that Gratiot County did anything to help those escaping Germany and Europe occurred at the Union Thanksgiving Service in November 1936. The Alma Methodist Episcopal Church took up a Thanksgiving offering to help “those pitiful exiles (who), with many Jews, have been driven from Germany by Nazi laws against ‘non-Aryans.” The church went on to state that since Jewish people in America helped fellow Jews, then the offering should be used to help Gentiles “to assist their own similarly.” Although the offering helped Gentiles in need, this event was the only one on record showing evidence that Gratiot County did anything regarding those escaping the Nazis and the impending Holocaust.

In 1937, readers of county newspapers also learned about the growing menace of the German Bund, organized by Fritz Kuhn in New York City. Through his group of American Nazis, Kuhn claimed that he had over 100,000 Americans who pledged support to the Bund and, in turn, Adolf Hitler. International tensions continued to rise as Hitler took Austria during the Anschluss in March 1937 and with the Sudetan Crisis a year later. Hitler was slowly absorbing parts of Europe. Otakar Prodrobsky, an Alma College student from Czechoslovakia, was immediately flooded with requests to speak to Gratiot County groups shortly after he arrived in Alma in the fall of 1938. Prodrobsky was from Prague and reported what it was like for him to live under the Nazis.

In Gratiot County, it took Kristallnacht, the extensive Nazi pogrom of November 9-10, 1938, to jolt some Gratiot County residents into learning more about the Holocaust. The editor of the Alma Record, H. S. Babcock, started his column “Uncle Sam and Hitlerism” with the story of what he had just heard in public. Babcock had someone tell him, “We are not interested in the German matter at all. If Hitler wants to kill off the Jews and take their property, that is their funeral and no concern of ours.” After spending six long paragraphs belaboring how trade relations between America and Nazi Germany had been damaged, as well as international relations, Babcock included excerpts of other columnists and their reactions to the persecution of Jews due to Kristallnacht. The column concluded that “A madness has been visited upon Germany. The disease is an old one: hatred; the cause: war.” The column did not call out Hitler and Nazi Germany for their persecution of the Jews for what it was – the expansion and implementation of a long history of European antisemitism. About all that the column concluded was that in the end, “the fever of blind hate will run its course…and destroy the Germans themselves.” A month later, the Alma Record carried the story that 300,000 people awaited permission to leave Nazi Germany for the United States and that ninety percent of the group were Jews. It also stated that only 27,370 could be allowed into the country based on current immigration laws. That meant it would take eleven years to work through the list even if the United States agreed to let that many refugees in. As a result of Kristallnacht, American consulates in at least four places in Nazi Germany became flooded with long lines of applicants wanting to leave the country.

In the spring of 1940, St. Louis hosted a significant witness to the growing Nazi occupation of Europe when Vojta Benes, brother to the former president of Czechoslovakia, spoke to 200 people at the St Louis High School auditorium. Benes had been active in politics in his country and toured the United States in 1938; then, he tried to return home just before Hitler took the Sudetanland. Benes fled to Poland and then found his way back to the United States. Benes described his country as “a prison camp for ten million people” under the Nazi Protectorate. He did not discuss the situation as it pertained to Jews in his country.

In May 1940, the Gratiot County Red Cross took up collections in Alma for civilian relief in war-stricken Europe. The leading Gratiot County supporters of helping these refugees were members of the Newark Mennonite Church, which gave the most significant sum – $157.00 for refugees. Two other anonymous contributions of $25 each were also given – and that was it for Gratiot County.

Even before Pearl Harbor, Gratiot County, like the rest of the United States, became scared of “enemy aliens” in its midst. A nationwide program started (as one did before World War I) to identify “enemy aliens.” In late August 1940, the county post offices began registering and fingerprinting Gratiot County’s aliens who had four months to register, or they faced possible arrest, six months in jail, and a $1,000 fine. All were required to fill out a form and answer many questions. The first asked how long they had been in the United States and how they got to Gratiot County. By January 1941, 976 aliens registered in the county, with Ithaca leading the group with 415 aliens. Postmaster James O. Peet believed that the large numbers his office encountered in Ithaca existed because Ithaca was closest to Gratiot County’s sugar beet growing area.

The War, Service, and Encountering the Holocaust

Gratiot County readily sent its young men and women off to fight in Europe and the Pacific after the events at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The Second World War began, and Gratiot residents read about Japanese relocation camps when a picture of the new Manzanar camp appeared in the Alma Record and Alma Journal on April 2, 1942. The news of these camps for Japanese Americans did not appear to stir any other reactions from Gratiot readers.

As Gratiot County went to war, it was common for some Gratiot County households to see sons from large families empty and leave. A group of four, five, or more sons going off to war sometimes occurred. In one case, the Klein Family of Ithaca, who was Jewish, sent five sons to fight and two more to military service after World War II ended.

Edward and Rella (Spitz) Klein moved to Ithaca from Grand Ledge sometime before the start of the Great Depression. The Kleins quickly became involved in the county by operating Klein Brothers Shell Service in Ithaca and a North Star furniture store. Edward Klein originally came from Hungary and still had family members in that country during the Holocaust. Records indicate that he had at least one relative who perished in Auschwitz, and there were probably more.

However, when it came time to serve Gratiot County during the war, all of the Kleins did their part. Franklin went first, entering early in 1941, and served with the 888th Ordinance H.M., Company Q in the China-Burma-India Theatre for two years. He also did another three years here in the United States. Royal, the oldest son, became a bombardier in the Army Air Corps, where he was wounded in action. Louis was the first to enter the Navy and served four years there. He later operated Klein Wall Paper and Paint in downtown Alma from 1949-1971.

Robert was a radio operator for 3 ½ years in the China-Burma-India Theater. Harold also entered the Navy and served in the Pacific aboard the USS Yorktown. Only 17, when he enlisted, Harold became involved in real estate after the war. Sons Richard and Milton served their country after the war ended. Richard later was in Korea. It is not clear where Milton served. However, the family confirmed that he, too, served his country.

The cost of the Klein family’s service in World War II was an extended family separation. It would be late February 1947 before the entire family again sat together at a dinner table. Fortunately, the Klein sons served their country and came home safely. Like some other large families in Gratiot County, the Klein brothers’ service appeared in the Gratiot County Herald for the many sons they sent to defend Gratiot County and the nation. Still, after the war, the family remained humble and quiet, humble, and went about trying to restart their lives.

News of the Death Camps Reach Gratiot County

That Hitler was carrying out the murder and extermination of the Jews of Europe was not unknown to Gratiot County residents. While Gratiot County newspapers did not explicitly mention the death camps, there were other ways that residents learned about what was taking place. In the summer of 1944, the Ionia Sentinel reported on the existence of Auschwitz Birkenau and how these victims came from several European countries. Likewise, the Owosso Argus Press ran a headline that the Nazis had murdered 1.715 million Jews in just two years. The first actual picture of a “slave labor camp” in the Vosges Mountains in eastern France appeared in the St. Louis Leader at Christmas 1944. The image mentioned how the SS used crematoriums to dispose of the bodies.

As Allied armies penetrated the Third Reich in April 1945, they discovered more concentration camps, and soldiers took pictures. An image of bodies found at Ohrdruf, Germany, was the first image of the Nazi genocide in the Gratiot County Herald on April 12, 1945.

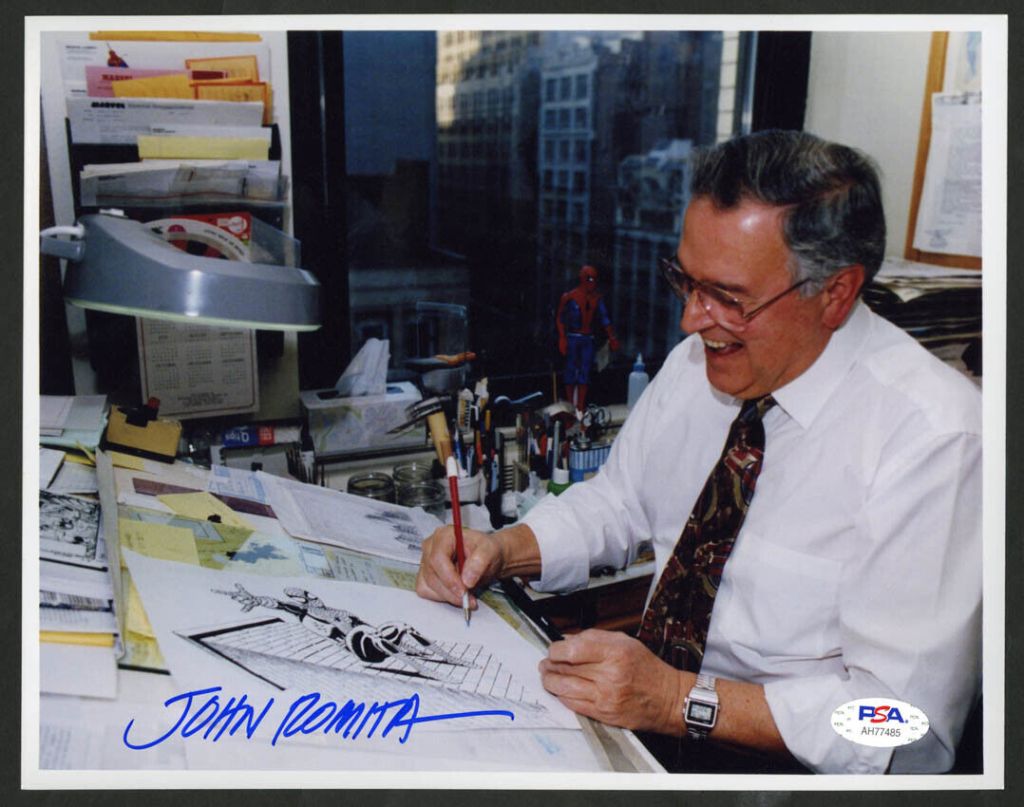

Written testimony from letters of Gratiot County liberators soon appeared in local newspapers after the fall of Nazi Germany. In a letter dated April 20, 1945, Major T. S. Nurnberger, Jr. of St. Louis, wrote about his experiences after entering Buchenwald in Weimar, Germany. It was nine days after Americans first liberated the camp. As Nurnberger stood at the entrance of the Buchenwald Camp, which was located on the edge of a mountain, he saw a sign that welcomed American liberators. Nurnberger learned that 51,000 people had already died in the camp. After visiting the crematorium, Nurnberger saw bodies stacked “like cordwood” and two badly beaten SS men whom prisoners had killed. He then could not believe the number of people crammed into the empty bunks inside some barracks. He wrote, “The stench was so strong despite recent cleaning that it almost made me sick.” The next place he saw was an old pit containing 1500 dead, which needed a bulldozer to cover them. Concluding his letter, Major Nurnberger added, “This is your Germany of culture. This is (the) why behind the unconditional surrender of the Third Reich. I have had a bad dream, you say! Ah yes, and I have the pictures to prove it taken with my own camera.”

Norval Biddinger of Middleton also saw Buchenwald and wrote home to his mother about what he witnessed. In a June 3, 1945, letter Biddinger began with his feelings about seeing the camp. He wrote, “I am mad all the way through and want to get this letter written while I still remember it.” He described seeing survivors who had “nothing left but skin and bones.” In one building, 1200 men were forced to live in barracks built for 100. Biddinger saw the crematoriums and recalled that prisoners killed 150 SS guards before the United States Army found them. Writing about its size, Biddinger said, “The whole camp covers an area no bigger than Middleton, and they crowded them in as many as 80,000 at one time.” Biddinger closed by saying that all his information was obtained firsthand from survivors still in the camp.

Other letters came to Gratiot County from men who witnessed the Nazi concentration camps. Private John D. Harnick of Ashley wrote about seeing furnaces and crematoriums but did not identify the camp. The same was true of Lloyd Peters of Ithaca, who was with General Patch’s Seventh Army.

Corporal Robert L. Brown of Ithaca saw the remains of murder at Gardelegen, where 800 prisoners were burned alive while trying to escape from a barn. Images from Gardelegen appeared in Life Magazine on May 7, 1945. The prisoners had been on a death march and were placed inside a 100 feet by 30 feet brick barn. A German Army sergeant saw the straw floor covered in oil, had the doors locked, and then set it on fire. Anyone trying to escape was shot by machine guns placed outside. After the fire, the Germans tried to bury some dead but could not cover the evidence before the Americans arrived. Only three people survived Gardelegen. Corporal Brown wrote about what he saw by stating, “I never witnessed anything so horrible in my life, and I hope I never shall. Ditches out in the back of the building were dug by these men before their cremation, I presume, but only a few were buried in them…” He closed, “Can you imagine such a thing? This doesn’t make for good reading. I know, but it is the truth…Perhaps you will read about it in the papers.”

Tony Kuna was probably one of Gratiot County’s longest-lived liberators. He later recalled and talked about what he saw. Kuna was in the 71st Infantry Division and attached to Patton’s Third Army as it penetrated Austria in early May 1945. Kuna was one of several liberators at Gunskirchen Lager, a subcamp of Mauthausen near Wels, Austria. Kuna’s division found a camp of 15,000 prisoners where approximately ten percent had perished. When Kuna entered one of the barracks, a prisoner begged for a cigarette. Kuna gave him one, thinking the prisoner wanted a smoke. Instead, the prisoner ate it, then suddenly died. Kuna recalled, “You don’t ever forget something like that. I was sent into the camp for guard duty and cried the whole time.” The Americans’ main problem with the survivors, as was in other liberated camps in 1945, was how to feed them. The se liberators met starving prisoners yet could not keep food down. At Gunskirchen, the best Army doctors could do was boil water and place bread in it to eat. In a twist, Tony Kuna’s experience with the Holocaust in Austria led to other lifelong connections. One survivor who later settled in Winsor, Ontario, Canada, once visited Kuna and brought a large meal to the Kuna home to remember this survivor’s liberation by the 71st Division at Gunskirchen Lager.

The Holocaust and Gratiot County After 1945

Although the war in Europe ended in May 1945, different parts of the Holocaust eventually came into contact with residents in Gratiot County. Coverage of the Nuremberg Trials started in November 1945. It ran for ten months as leaders of Nazi Germany went on trial for war crimes. In December, it was written that upward of 6 million Jews had been murdered in Hitler’s Holocaust. Sergeant Roy King, whose mother lived in Alma, was a member of the military police at Nuremberg and sat in the press gallery as an escort for General Powell. King wore earphones and heard the broadcast of the trial in front of him in five different languages.

Even before the trial concluded, the proceedings appeared in eight volumes for each Michigan county that wanted copies. Gratiot County Circuit Court Judge Paul R. Cash announced that the books would be purchased and placed in the county courthouse law library where anyone could read them beginning in early 1947.

There would be other reminders of the Holocaust in Gratiot County after the Nuremberg Trials ended. Smaller trials of other Nazi perpetrators took place for a few years afterward. However, by 1950 the so-called “trials” for other criminals ended, even though countless Nazi perpetrators evaded justice. When Nazi perpetrator Adolf Eichmann’s trial occurred in the early 1960s, news and references to the Holocaust briefly appeared in newspapers. Probably the biggest stirring of memory and discussion of the Holocaust came to Gratiot County, as did other places in the United States when the NBC miniseries “The Holocaust” appeared on television in the spring of 1978. The story of the Family Weiss confronted Americans about the Holocaust and brought it to the forefront of American memory. Another encounter with the memory of the Nazi genocide occurred in the early 1990s when the movie “Schindler’s List” was shown in movie theatres. In response to the film, Michigan legislators made it possible for students, including those in Gratiot County, to go and see “Schindler’s List” at the Alma Cinemas. There would also be other avenues that Gratiot County residents could use to learn about the Holocaust. The Zekelman Holocaust Center (first known as the Holocaust Memorial Center) in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, opened to the public as the first Holocaust Memorial in the United States in 1981. In 1994. the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum opened in Washington, D.C., in 1993, and students visited there on group or individual trips.

Gratiot County residents knew about the Holocaust. What we learned about and what we actually did about it (and often did not do about it) were two different things. What we did do aside from financial support from what two churches and service members did in Europe is – not much.

Copyright 2023 James M Goodspeed