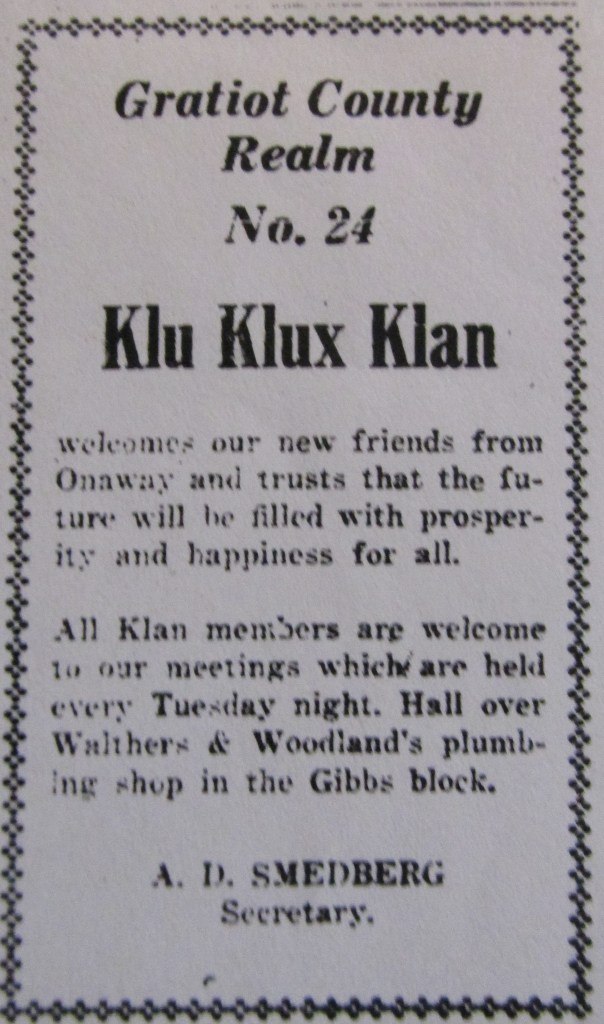

Above: Some members of Gratiot County Ku Klux Klan Realm No. 24 members appear at July 4, 1927 Klan gathering in Jackson, Michigan; a Klan publication that belonged to a Michigan KKK member in the 1920s; President Harry Crooks of Alma College became a KKK target when refused to let Alma College students attend Klan activities or become Klan members in Alma; an advertisement from the Alma Record sponsored by the Gratiot Klan – and which identified one of its members who later ran for mayor of Alma.

The Ku Klux Klan first appeared in Gratiot County just over 100 years ago. For a short period of time, the Klan flourished by conducting parades, recruiting members, holding meetings, harassing targets, and by trying to connect with county churches. The following is part one of a four part series about Realm No. 24 and its activities in Gratiot County – during a place and time that was fertile soil for the KKK.

One evening in January 1923, Detroiter A.G. Struble witnessed an unforgettable sight as he drove north along the old Alma Road, just inside the Gratiot County line. While taking his family to Mt. Pleasant to attend a funeral, Struble met five men on horseback fully dressed in Ku Klux Klan apparel, each with long spears and lights. Although called to stop, Struble kept driving.

The presence of the Klan in Gratiot County during the 1920s was part of a movement that swept across parts of the United States, spewing its anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, and anti-Jewish message. Boasting its “100% American” agenda, the Ku Klux Klan supposedly stood for law and order, control of alcohol, support for public education, and, above all, white Protestantism. Nationally, the KKK claimed a membership between two to five million people, with its most substantial followings in the Midwest. Michigan had the nation’s eighth-largest membership, with 70,000 Klansmen.

Starting in 1923, Gratiot County became the home of Realm No.24; for three of those years, “Klan fever” attracted both followers and those curious about the Klan. In October 1923, the first attempt of the Klan to recruit members drew between 500 and 700 people and took place south of Alma. Later in December, the Klan burned its first cross on Christmas Eve in town.

The Klan was most active in 1924 as it tried to gain credibility with local churches by either holding services, gaining the support of pastors, having Klan members attend a church, or offering a public gift. If the Klan could obtain the support of a pastor or gain his membership, it would gain access to another audience. This connection between the Klan and church happened in Alma when the Christian Church held a Klan-sponsored revival meeting, and the pastor gave sermons in support of the Klan. If an announcement from a church stated that the preacher would provide “A Christian Interpretation of Klancraft,” it was a pro-KKK message.

I In Alma and at the Breckenridge Baptist Church, the Klan exhibited one of its 1920s trademarks: the use or donation of “the Illuminated Cross.” With the lighting of the new cross in the sanctuary, Klansmen would march down the aisles and sing “America.” Klansmen also knelt at the altar while playing “The Old Rugged Cross.” All occurred to impress the congregation and send a message that the Klan was in the community, supposedly in numbers large enough to warrant attention and support.

As the KKK began to take off in 1924, it started its first attacks upon local people and groups that it deemed to be its enemies. It first did this through an often-used weapon – the local KKK newspaper, The Nighthawk. When Alma College President Harold Crooks urged students not to listen to or attend Klan recruitment meetings, he then became a target.

Using The Knighthawk, the Klan falsely accused and slandered Crooks by accusing him of having pro-German sympathies during World War I. In response to the attack, approximately one hundred Alma College students marched two abreast from the college through downtown Alma to the Klan headquarters at 210 ½ East Superior Street. Upon arrival, the students purchased all available copies of The Nighthawk, formed a circle, and publicly burned them, shouting, “Yay, Prezi!” To commemorate the protest, the Alma College yearbook that year featured a picture regarding the burning and captioned it: “Kluck! Kluck! Kluck!”

Copyright 2023 James M Goodspeed