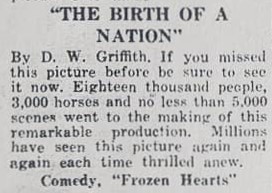

From top to bottom: Realm No. 24 welcomes Lobdells to Alma – and identifies a Klan member; more than one county theatre, like Ithaca’s Ideal Theatre, sought to cash in on Klan activity during the mid-1920s by re-showing “The Birth of a Nation” – which glorified the Klan; “The Sower” links American patriotism of the 1920s and the Ku Klux Klan, dated July 15, 1924; Ku Klux Klan items from the 1920s on display in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan as they appeared in 2009.

The following is another in a series of articles on the Gratiot County Ku Klux Klan, which was very active in the county during the 1920s.

Following the aftermath of the King-Garner Trial of 1926 in Ithaca, the decade gradually saw the decline of Gratiot County Realm No. 24. The attention that the trial brought to Gratiot County, along with a national decline of the Ku Klux Klan following a sex and political scandal in Indiana, led to the erosion of its popularity.

However, the Klan still had its supporters and followers. Names like Otto Hawley and Herbert A. Becker of Alma, Margaret Smith and R.A. Anderson of St. Louis, G.W. Anderson, James and Margaret Esenlord, and M. Alspaugh of Arcada Township all posted bail for Lewis King and the Garners during their trials in Gratiot County. One of the supporters admitted in newspapers that he even invited King to Gratiot County to hold his religious meetings.

Out in Arcada Township, the Ku Klux Klan campground attempted to make a go of it – and did for at least two years. At one point, it advertised itself as a haven for Klansmen, Tri-K Girls, American Krusaders, and Junior Klansmen. The campground eventually closed, probably due to lack of financial support, or the owners possibly decided to end the farm’s designation as a Klan gathering spot.

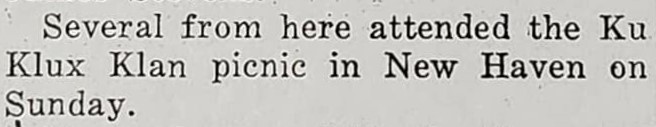

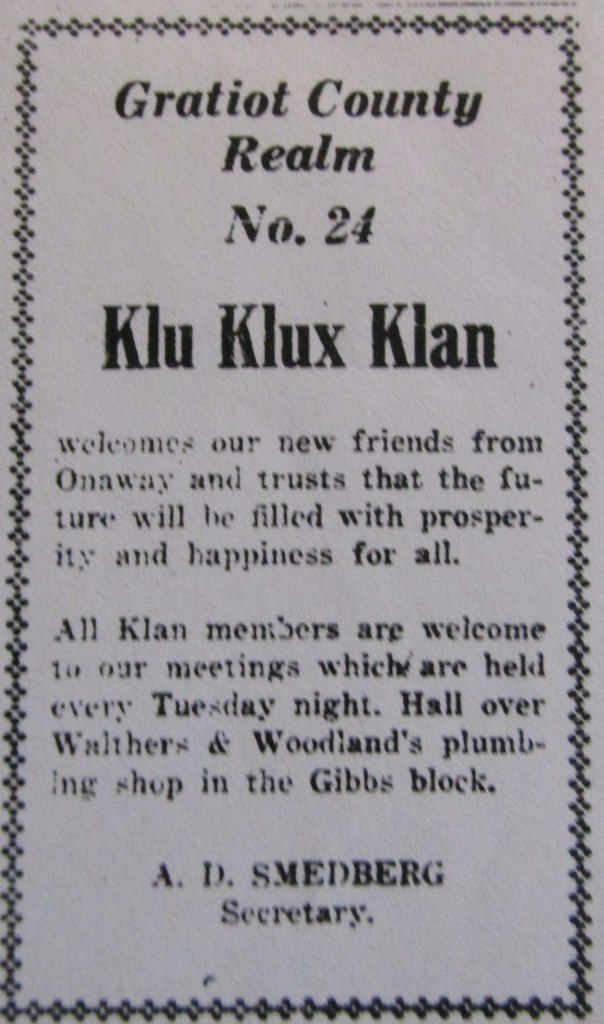

An exciting event occurred in the Alma Record in 1926 when the newspaper welcomed Lobdell Emery from Onaway, Michigan, to Alma. Among those groups buying ads welcoming this new company to Alma was Gratiot County Ku Klux Klan No. 24. The advertisement stated that it “Welcomes our new friends from Onaway…All Klan members are welcome to our meetings, which are held every Tuesday night.” Beneath the ad, Klan secretary A.D. Smedberg of Alma signed his name. Smedberg attended the University of Michigan and Ferris Institute and later was the purchasing agent for New Moon Homes in Alma. Smedberg also ran for Mayor of Alma.

Another name from the Gratiot Klan slowly surfaced. At Alma College, one member of the Board of Trustees was Klansman Stephen S. Nisbett, active in the Newaygo County KKK and President of Gerber Baby Foods. He eventually served on the board for 22 years.

The historical record is scant regarding those who took a public stand against the Klan. One of these, Reverend R.A. Gelston of the Alma First Presbyterian Church, went to the pulpit one Sunday to declare that the Klan had no place in Alma and that people should be aware of its divisiveness and damage to the community. During the peak of Klan activity in Alma, one could also read statements in church notices during its height. One could attend an evening service about “The Fiery Cross ” at one end of town.” Up the street, another church countered with “The Cross on which Christ Died.”

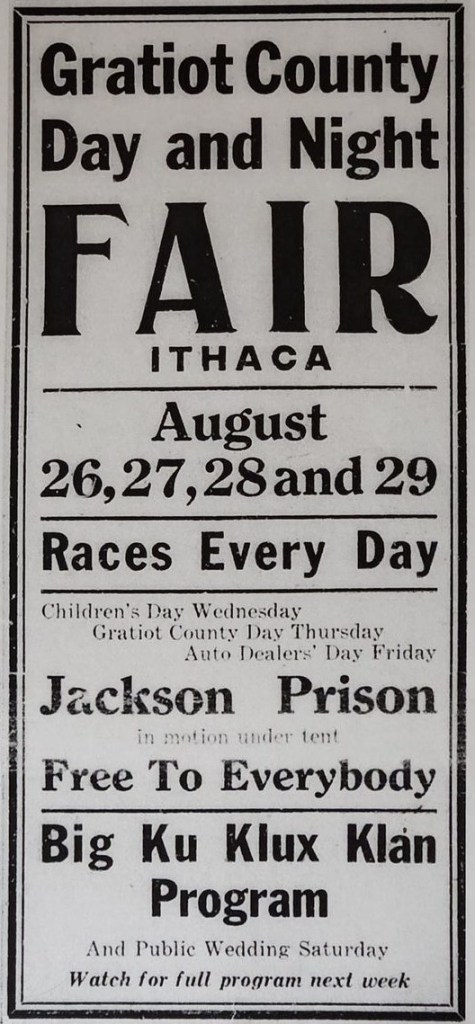

In Alma, the Klavern operated its headquarters at 110 ½ East Superior Street until at least 1931. Before its demise, a popular activity of the Gratiot Klan was holding picnics at places like Crystal Lake in Montcalm County, complete with a good, old-fashioned sermon. During one Christmas at the start of the Depression, the Klan announced that it would distribute Christmas baskets to needy families in the Alma area. Realm No. 24 also periodically trumpeted the importance of its meetings – such as when the Grand Dragon of the state Ku Klux Klan, George W. Carr of Owosso, appeared in Alma.

For some in Gratiot County, Klan enthusiasm was slow to pass. While the Great Depression took place, it was common for families to hold weekly house parties for entertainment. One group from Arcada Township did so at the former location of the Klan campground. What was the group’s name for its monthly parties? The Klitter Klatter Klub.

Next time: Part V. “Klan Confusion – What Should Gratiot County Learn from the History of the KKK?”

Copyright 2023 James M Goodspeed