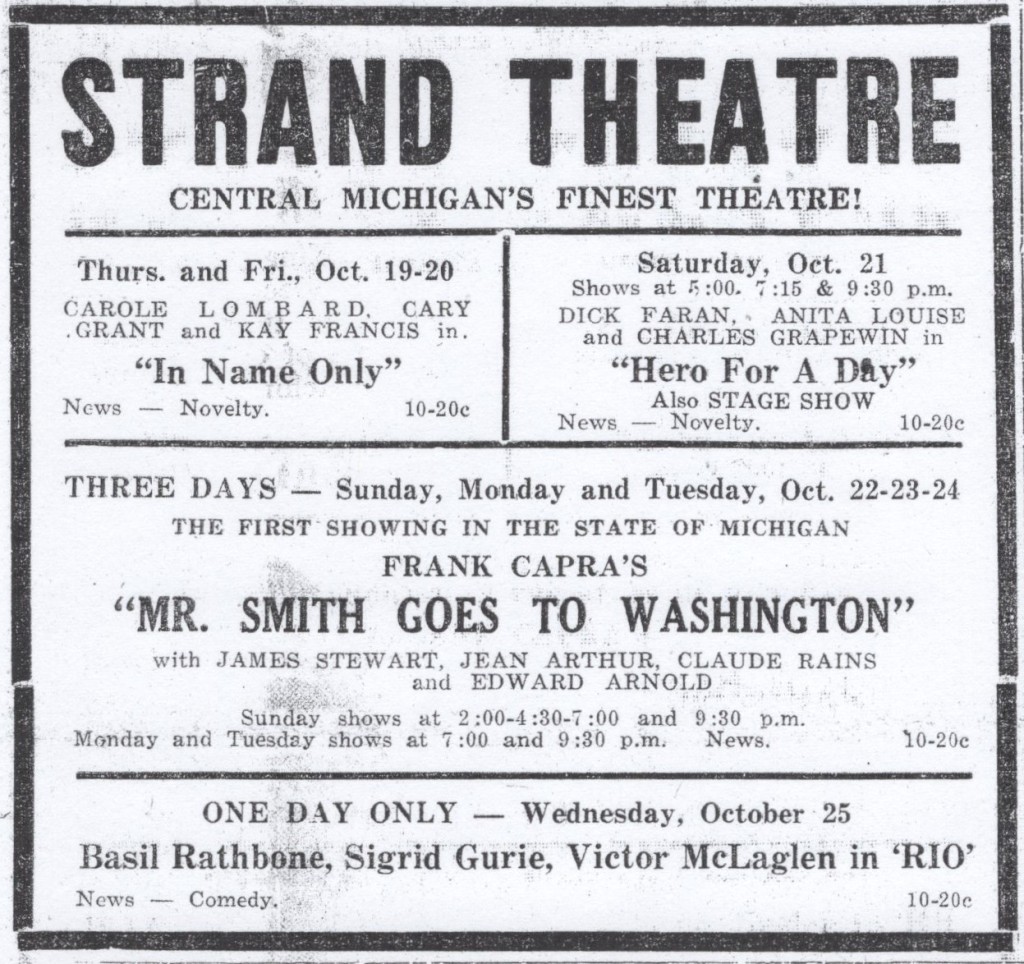

Life in Gratiot County during October 1939: Balmoral Patricia, a nine year old Ayrshire from Ithaca’s Balmoral Farm, found herself in Borden Dairy World of Tomorrow at New York World’s Fair; Jimmy Stewart starred in “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” at the Strand Theatre in Alma. “Mr. Smith” would become one of Stewart’s most famous movies; the “Phony War” started in Europe. When would the Nazis invade Western Europe? The battle lines in November 1939 appeared strikingly similar to those of the First World War.

The Great Depression continued into its eleventh year. Some in Gratiot County wondered, was it now beginning to end? People seemed to be finding jobs and doing more seasonal work.

A world war entered its second month. How long would it last? Would the war follow similar patterns to the World War two decades earlier?

It was October 1939 in Gratiot County.

A World at War

The war situation was the start of Hitler’s “phony war” and encompassed the next eight months in Europe. As Western countries like France and England anticipated a Nazi move west, both sides prepared for a deeper conflict. Names like “Siegfried Line,” “Maginot Line,” and “Armistice Front” became a part of the newspaper’s coverage to educate the American public about what was happening with Nazi Germany.

Rumors of German submarines patrolling near the Panama Canal raised concerns about the United States’ interests in the canal. Local newspapers also told readers that the war would undoubtedly affect the nation’s cost of living. No doubt, war business (like munition sales) would boom. This could mean more jobs for those who needed employment.

New Deal Programs Continue in the County

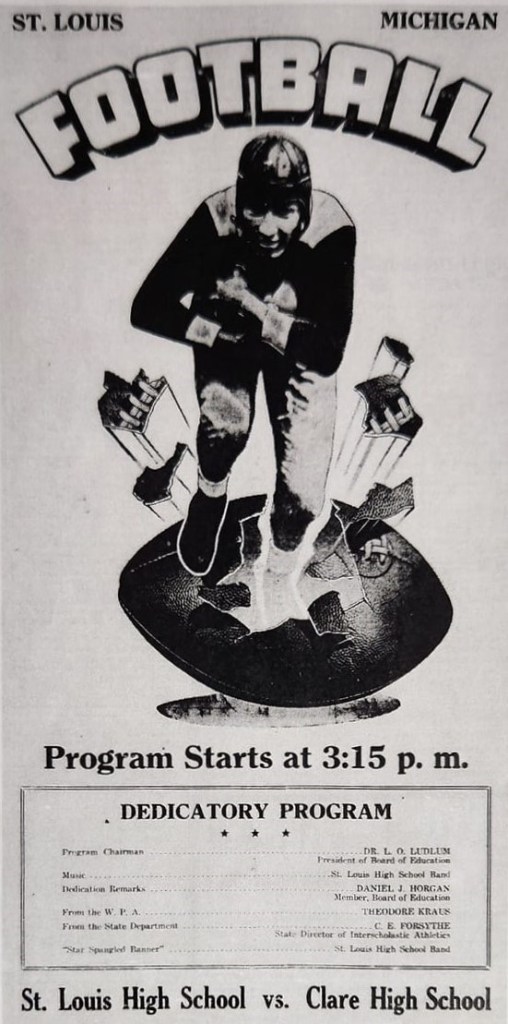

One of the essential New Deal programs that gained notoriety in October centered around Wheeler Field in St. Louis. The first game and dedication of the new field occurred on the afternoon of Friday, September 29. The game against Clare began at 3:00 pm in heavy rain, which continued for most of the afternoon. During half time, a program involved speakers from the Board of Education, Works Progress Administration, and the State Director of Interscholastic Athletics. The field was then officially dedicated and opened in memory of Dr. Aaron Wheeler, St. Louis doctor, mayor, and former school board member. The St. Louis Crimson Tide played hard but lost a wet game to Clare by the score of 24-12. Newspapers reported that the St. Louis team played much better than the previous game’s loss to Ithaca.

The Gratiot County Board of Supervisors in Ithaca dealt with the issue of welfare reorganization. Under new laws, welfare relief ended up in a dual system in the county. This policy now meant that one bureau oversaw federally funded programs and aid. A second bureau, called the “Bureau of Social Welfare,” came under the control and distribution of the county. One of the second bureau’s goals included weeding out those applicants who were not needed (whom county newspapers called “chiselers”). The board reported that the County Poor Farm budget for the upcoming year would be $7,000 for the farm’s operation.

The National Youth Administration (NYA) planned to offer girls’ sewing projects under the direction of Dean Carter, NYA county supervisor. This work provided work for 25 girls between the ages of 18-25 who worked no more than 64 hours a month (50 hours in work, 14 in training). Part of the reason for offering a sewing project for girls was that most of NYA’s previous programs interested young men more than women. Works Progress Administration projects (WPA) in the county continued to center around street pavings in Alma – notably around East End and Walnut Streets.

However, with the sugar beet factories opening, at least 28 men from an original crew of 161 had left to take other jobs. Wet weather and cold also hampered the completion of the work on the streets. The Alma city manager was allowed to hire another 60 men to get the job done.

Ithaca offered fall programs under the direction of the WPA, which included boys’ and girls’ craft rooms. Adult groups met on Tuesday nights and offered a Psychology Club and Ladies’ Recreation Club. They provided a girls’ and boys’ music club on Thursday evenings. On Saturday afternoons in Ithaca, a younger boys and girls club met for four hours. One activity enabled 35 youngsters to go to the park for games, study nature, and make winter gardens. A Lady’s Recreation club met on Tuesday evenings in the Village Hall. Grace Rowell led the Ithaca Recreation Program under the sponsorship of the Ithaca Village Council that month.

Gratiot County also needed to fill the full quota of those who could join the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Although ten could sign up, only nine young men from the county went to Munising for winter quarters. Between this news and the trouble of finding enough workers for WPA street work in Alma, some thought the national economy might be improving.

Farming Season Turns Toward Harvest

With the coming of October, beet harvest and factory operation were on the minds of many in the county. In places like Alma and St. Louis, the familiar sights of trucks loaded with sugar beets again could be seen and heard. In anticipation of the fall harvest, the Gratiot County Conservation Association called attention to the Child Labor Provision in the 1937 Sugar Act. It reminded farmers that they could only employ children under the age of fourteen in the fields if the child belonged to that farmer’s immediate family or if they had at least a 40 percent interest in that crop.

By the end of the first week in October, beet slicing began at plants in Mt. Pleasant, Alma, and St. Louis. The Alma plant employed 400 men and was expected to run for 60 to 90 days while slicing 1,500 tons of beets daily. St. Louis expected an 80-90-day run with an anticipated slicing of 1,000 tons daily. The three plants together employed 1,050 men and required 3,000 field workers.

Regarding daily life, danger was always present on Gratiot farms. W.A. Alward of St. Louis, age 53, was viciously attacked by his bull when the animal broke its chain. The beast, weighing 600 pounds, knocked Alward down and rolled him several times. Luckily, Alward’s son was nearby, and the family’s dog distracted the bull enough so that Alward could be pulled from the pen. Alward suffered severe chest wounds, two broken ribs, and one pierced his lung and was taken to Smith Memorial Hospital. Three weeks later, Alward died from the injuries as the result of an unexpected blood clot.

Fred McLean of Breckenridge suffered the loss of his horse when hit by an automobile. Gerald Powelson was driving the horse hitched to the wagon when it was hit by a Dodge Sedan. The car was driven by a Saginaw man, and the horse had to be put down due to a broken leg.

A farmer’s greatest fear was losing his house or barn due to fire. One afternoon, Clarence Pitscher’s small barn at Benson Bailey Corner on the River Road north of St. Louis was a complete loss even though the St. Louis Fire Department arrived to try and contain the blaze. It turned out that children playing in the barn first discovered the fire. In another instance, Sherman Sommerville lost fifty-one sheep and one colt during a fire six miles southeast of Ithaca. This fire was estimated to be a $5,000 loss and was the third fire in that community during the past few months. Sommerville had partial insurance on his barn.

Aside from the start of the beet harvest, a big concern on the minds of Gratiot farmers had to be the upcoming pheasant season in the county. At the beginning of the season, many farmers feared the many pheasant hunters who came from outside of the county. These “nimrods” seldom asked for permission to hunt on farms and frequently left gates open and damaged crops as they pursued Ringneck pheasants. Just before the start of the season, approximately 100 hunters bought licenses in St. Louis, and these were probably local hunters. In anticipation in the Lower Peninsula, the state planned to hire approximately 100 special duty sheriffs to help monitor what was expected to be the biggest pheasant season ever. Nine communities in Gratiot County opened as hunting co-operatives with the message: ask landowners and farmers for permission before you hunt. Also, observe posting signs established by farmers who did not want hunters on their property.

There were other happenings in the area of Gratiot farming in October. Dog tax fees remained unchanged – $2 for female dogs and $1 for male or unsexed. Part of the dog tax collection fees went to farmers who lost animals (usually sheep) due to attacks by dogs. The Emerson Farm Bureau met at Beebe Hall, but attendance was down due to work in the harvest. Clarence Muscott served as chairman. Allen McPherson, North Star farmer, announced that his Holstein cow just gave birth to its fourth consecutive pair of twin calves. James S. Davidson of Balmoral Farm, Ithaca, displayed his nine-year-old Ayrshire at the New York World’s Fair. Balmoral Patricia was one of 150 fine purebreds from farms nationwide that appeared at the fair.

The state turkey tour came to Gratiot County on October 26. During the tour, the group saw an estimated 12,500 turkeys on 11 area farms. The tour started at C. W. Hoyt’s farm eight miles north of St. Louis, where he had 400 heads of Bronze breeders. It would end on the James Wright farm in Maple Rapids, where he had 4,700 Narragansett turkeys. During the tour, the Michigan Turkey Growers Association offered turkey sandwiches, coffee, and doughnuts for lunch.

At the end of the month, 315 boys and girls from across Gratiot County completed their 4-H Club summer projects. An achievement day occurred at Ithaca High School, featuring the displays of the largest summer enrollment of 4-H members ever seen. Canning, food preparation, baking, sheep projects, Dairy projects, and garden projects were just some of the categories for those who participated.

Pheasant Hunting Season Arrives – Gratiot Prepares for Invasion

An invasion was coming to Gratiot County that fall – this time in the form of pheasant hunters who arrived from outside the county.

During September, Gratiot County encountered a rash of hunting dog thefts. In ten days, thieves made off with over a dozen prize-hunting dogs (mostly Beagles and Setters) from farms across the county. Conservation and police officers surmised that the dogs were probably taken out of state and sold. One dog south of Alma was valued at over $150 and was stolen one night while the family was asleep. Hence, farmers and hunters were warned to lock their dogs up at night.

Nine communities offered hunting co-operatives under the Williamston organization plan to control hunters outside Gratiot County. Those hunters who followed the plan had to park their car in the farmer’s yard, ask for permission to hunt, get and wear a ticket, and report what game they took at the end of their hunt. If a hunter saw a sign that read “Game Management Area, No Hunting Without Permission,” they had to follow these guidelines. Hunters also had to hunt in the square mile of farmland the ticket was assigned, but there was no fee for hunting. Some game areas that hunters could use were in Northeast and Northwest Seville, Pine River, Arcada, Pine River, Sumner, New Haven, and North Shade Townships.

Hunting had been judged good toward the end of the pheasant season in 1939. Several Alma hunters had their season limit of six birds in the first three days of hunting. Regarding controlling outside hunters, some followed the Williamston plan, while some did not. Several county farmers declared they had unwanted hunters on their property, even after posting no hunting signs. The Alma Record sold many of these signs. Still, almost a dozen hunters ended up in court with fines for trespassing. Two Detroit men were arrested for possessing pheasants before sunrise on opening day. Two more pled guilty after being caught without a license. Charles Sabatovich of St. Louis and Gene Coon of Ashley were cited for hunting before sunrise. Kenneth Richards of Perrinton was the only one cited for violating the Horton Trespass Act upon complaint by Charles Kilean of Fulton Township, who argued that Richards shot game on posted property. Richards ended up paying $17.85 in fines and costs.

The Long Arm of the Law in Gratiot County

The new jail in Ithaca could hold fifty people; however, only eleven prisoners resided there in early October. Ruth Wonnacutt, the wife of an Alma ice dealer, was held for ten days for assault and battery on her stepson. Wonnacutt thus became the first woman to be held in the new jail. Cecil Richards of Alma received ten days and a fine for hunting in a game area without a license. From Merrill, Ralph Rudd, age 23, got caught spearing fish on the Pine River in Sumner Township. He was re-arrested when he could not pay his fine. Raymond Shepler, age 28, of St. Louis, was arrested for stealing electricity from the city. Shepler contrived a device to acquire electricity without paying for it. He pled guilty and paid a fine of $15. On a lighter side, Elmer Reed, age 53, of Detroit, admitted himself to the jail for a night’s lodging and breakfast. Reed received ten days in prison and a fine of $6.35 for vagrancy.

In September 1939, 62 people were convicted of breaking the law. Of these, 42 paid their fines for traffic violations. The county collected $444.35 in fines and costs from all lawbreakers.

In Alma, a new law went into effect for jaywalkers. Those who wandered wherever they wanted to cross a street, crossed during a red light, walked on the right side of the highway, or walked on a road that boarded a sidewalk were violators who now faced arrest.

Van Smaley of Perrinton, age 20, escaped a severe car wreck and crawled out of his automobile one Tuesday morning. The Smaley vehicle went off the highway, taking out a telephone pole and a distance of fence before stopping. His car was a complete wreck. Kenneth Peters, age 26, met Smaley at an intersection south of Ithaca on the fairground road and also suffered severe damages to his car. Part of the cause for the accident centered around Smaley going 55 miles per hour and a cornfield obstructing the corner. Peters was also lucky to have survived the incident.

Gratiot County also received a lady deputy sheriff—probably for the first time in the department’s history. Miss Frances Nagel, age 19, of Wheeler Township, graduated from high school and business school. Nagel was in charge of the new jail’s automobile operator’s license bureau and earned $15 a week for her salary. She took over the new job when Deputy Charles Powers shifted to night duty at the new jail.

And So We Do Not Forget

The Gratiot Rural Teachers Club Unit I met at Mrs. Elizaebeth Blackman’s home. The club welcomed any rural teachers from Bethany, Emerson, Lafayette, or Emerson Township. Twenty members and visitors enjoyed a chicken supper served Frankenmuth style…The Alma Child Study Club led a group of city organizations to start preparing plans for helping underprivileged children at Christmas…The search for oil at Smith Number 1 wildcat in New Haven Township was given up as the location was found dry…Fulton Township High School principal Marian Woodford announced that each class was responsible for presenting a school assembly program every two weeks. Henry Parfitt was elected President of the Class of 1940, Marjorie Todd as Vice-President, and Martin (Chick) Richards as Secretary-Treasurer…Jack-O Lanterns were sold for five and ten cents each at Gay’s in Ithaca.

North Star School held its first school fair on October 19 and 20. The event featured agricultural exhibits, rural school field day races, and contests. A total of 228 entries were entered at the school exhibit, and six rural schools took part…”The Mystery Man of the Movies,” Captain John D. Craig, kicked off the first meeting of the Town Hall series at the Alma High School auditorium. Craig showed color movies of his adventures as a deepsea photographer to 700 people…Three pounds of lard cost 25 cents at Barrone’s Market in Ithaca…Elmer Warren McDonald, a Spanish-American War veteran, died. McDonald served the country from June 30, 1898, until the end of the war.

The Ithaca Chamber of Commerce planned a Halloween party for boys and girls on October 30…T.A. Beamish and his wife rushed to Detroit upon hearing that Beamish’s mother died as a result of complications from rabies. Mabel D’Haene had been bitten by a dog several weeks previously. She took the serum, but the end came in the form of complete paralysis. The mother was buried in Hemlock Cemetery…1940 automobile licenses went on sale, featuring a black on silver design. Licenses could be purchased at county branch offices in Alma and Ithaca…A committee recommended that the Gratiot Board of Supervisors construct a new garage for the county road commission.

The Ithaca Elevator Company offered a complimentary color and talking movie at the Ithaca High School gym entitled “Vitamins on Parade.” Dr. Cliff Carpenter planned to speak on “Solving Our Poultry Problems”…New York Yankees’ first baseman, Lou Gehrig, was appointed to the New York Municipal Parole Commission at $5,700 a year. Gehrig recently retired from baseball due to what would later be called “Lou Gehrig’s Disease”…St. Louis teachers turned in a large pile of oath forms to Superintendent T. S. Nurnberger. All people holding a Michigan teacher’s certificate had to file a notarized oath of allegiance…The Christian Church at East Saginaw and Franklin Streets in St. Louis had Bible School, two preaching services, and Christian Endeavor classes each Sunday. David Moore served as pastor…The city of Alma advertised the sale of city lots to be held on Saturday, October 14. A total of 25 lots were up for sale.

John Bickel of St. Louis was accidentally shot by his younger brother, Harley when he discharged a .22 caliber rifle while getting ready for school early one morning. The older Bickel, luckily, was only struck through the abdomen, with the bullet passing through the left side of the ribs. Dr. R.L. Waggoner was called in and took the boy to Smith Memorial Hospital. Still, the wound was pronounced as not being serious. Still, Harley Bickel received an anti-tetanus serum to prevent infection…St. Louis planned a big community Halloween party on October 31 for young people in the city. A parade started from the high school and marched downtown before the judges’ stand. Some of the categories included “Most Original Costume,” “Oldest Couple,” and “Largest Group.” Cider and doughnuts awaited all who participated. Cliff Carter, a St. Louis High 1936 graduate, played center on the Alma College football team. Carter was considered for all MIAA honors due to his play in that position…Should the City of Alma go to parallel or angle parking? While city streets connected to parts of state trunk line highways had to shift to parallel parking, the city commission remained undecided on the issue…the Recordio, which combined radio, phonograph, and public address system for making recordings, debuted at Sawkins Music Horse at 208. E. Superior. No price was advertised…Several Alma stores displayed Halloween novelties and masks through window displays. Need a Goblin costume?

The Jean Bessac Chapter of the Daughters of American Revolution was organized at the home of Miss Lou Nickerson at 211 West Downie Street. Twenty Daughters of the American Revolution were present for the meeting. Nickerson was a direct descendant of Jean Bessac. The next meeting was scheduled for November 2…Michigan Bean Company of Alma sold Kopper’s Coal, which is dirt-free and virtually ash-free. Phone 270 for details…Veterans and their families were invited to attend a Halloween party at the American Legion Hall on October 31. Legionnaires were also invited…R.B. Smith Memorial Hospital had its annual meeting. Doctor H.B. Lehner chaired the meeting, and secretary Mrs. Sadie Soule read the minutes…The George Myers Post planned the 21st annual Armistice Day observances in Alma. While planning to have a colorful parade, musical units, and a short program at the intersection of State and Superior Streets, one of the challenges this year would be that Armistice Day fell on a Saturday…Alma High School announced the purchase of fifty new band uniforms, all in school colors.

Several fire alarms went off in Alma by mid-October. Two called for assistance; one was a false alarm. Fire number 31 of the year was a false alarm. Number 32 went out to the Fred Gilkins farm on Grafton Avenue. The fire caused $10 in damage before being put out with chemicals and water. Number 33 took place at Model Bakery when an overstocked coal bin pushed boards near a heater on the wall. That fire caused $150 in damages. Another false alarm occurred when a woman called Fire Chief Fred Stearns and set off an alarm. She did not know it, but Stearns’ phone had been connected to the fire department office. The woman also did not realize that the Alma Fire Department used volunteers…Bert Gee of New Haven Township was killed while digging a slush pit for an oil well. Gee worked 11 miles west and one-half mile south of Ithaca. Gee, age 65, suffered a heart attack. He left a wife and a young son…Phone 646 to reserve a lane to bowl at Alma Recreation on weekdays from 10:00 am to 12:00 pm or Sundays from 1:00 pm to 12:00 pm.

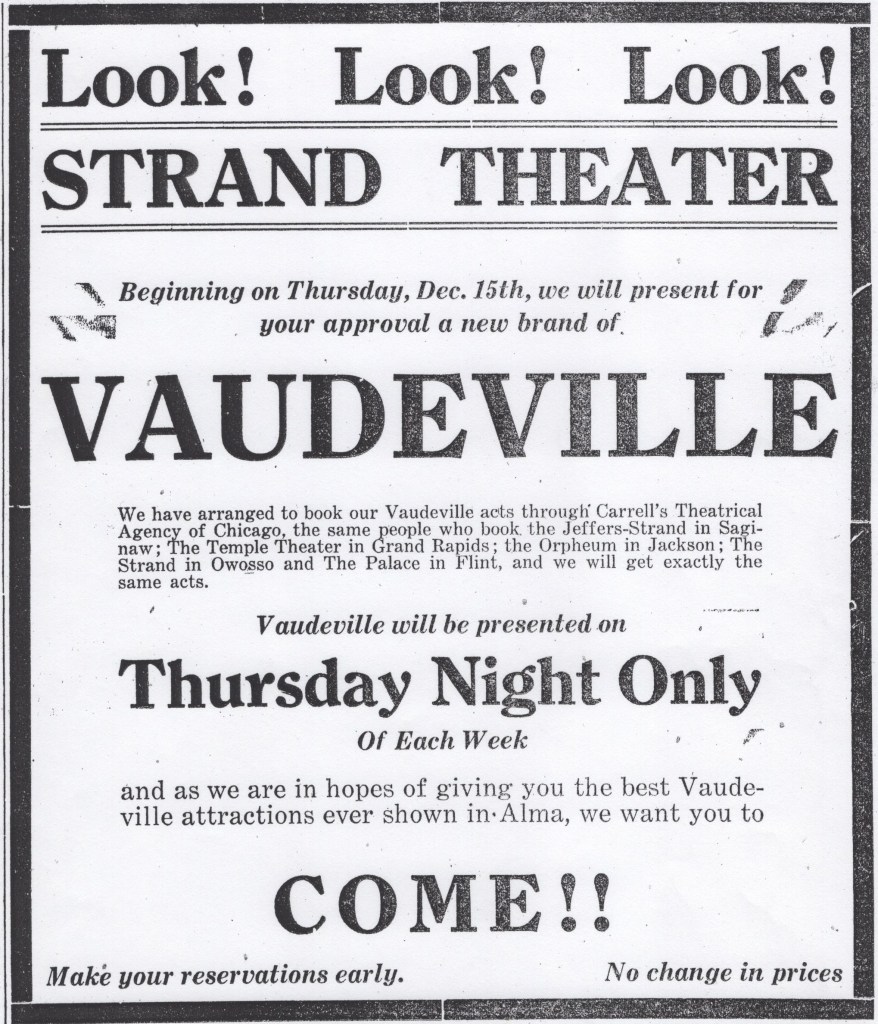

”Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” opened at the Strand Theatre for three days. This picture was the first showing of the movie in the state of Michigan. Jimmy Stewart played the lead role in this movie, which had a run time of 2 hours, 30 minutes…Michigan continued to lead the drive against pneumonia. Serums were available for Types 1 and 2…One of the new things people noticed in Alma bowling alleys was the debut of new team shirts. The names of sponsors appeared on the back of each shirt…Should the City of St. Louis purchase the Gratiot County bank property at Mill and Center to be used for a city hall? This was the decision voters would face in April…Dr. Merton S. Rice, a well-known Methodist pastor and nationally known speaker, appeared at Alma’s First Methodist Church. A large crowd was expected to attend…The first meeting of the Alma Lions’ Club occurred in attorney J. David Sullivan’s office in Alma. The group was expected to begin with a charter membership of 20 people.

Mrs. Jennie Miner purchased the first brick building built in Alma. The Delavan House was completed in the fall of 1881 and was considered the finest home in Alma for many years…Carol Lee Monnette, born in St. Louis and granddaughter of Mr. and Mrs. A.J. Davis, appeared on the Milton Cross Bus Program over a New York City radio station. Lee was five years old and sang “Oh, Something Has Happened to My Little Bisque Doll”…Sherman Summerville lost his barn in an undetermined blaze that cost him $5,000. He lost fifty sheep, valuable machinery, and much hay and grain.

And that was Gratiot County during Depression and War in October 1939.

Copyright 2024 James M. Goodspeed