From the top: The St. Louis Park Hotel prepared for the annual “President’s Ball” to raise money for the fight against infantile paralysis; the New Year began with more calls from President Roosevelt to prepare and arm the great “arsenal of Democracy” in wake of the war over England; “Gone With the Wind” made its second appearance in Alma – a tradition of reappearing at least once each decade until the Strand (II) closed in the early 1990s.

Christmas and New Year’s ended quietly in Gratiot County, but talk of America’s involvement in the European war increased.

Another group of young men left for the military even as a line of volunteers dwindled, meaning that the draft board would soon be forced to call men to serve.

The National Youth Administration remained very active by taking in young people to work on various projects.

And winter hit Gratiot County, sometimes shutting down towns and villages, even for just a day or two.

It was January 1941 in Gratiot County.

The Holidays Pass Peacefully

Just before New Year’s, local towns and villages revealed the winners of their Christmas home lighting contests. Milton Townsend, chairman of the St. Louis contest, announced that Carl Johnson of 422 East Washington won first place and was awarded five dollars. For the first time in St. Louis, the city sponsored the contest, but for some reason, there were fewer entries than in 1939. The Alma Chamber of Commerce awarded first place to Paul Woodland of 510 Republic Avenue (personal home) and to the Michigan Masonic Home (institution/business category), which received $10. Over at Breckenridge, the Garden Club rated B.C. Wood first place for the most original display; Mary Shepard got second for the most appropriate; Doctor E.S. Oldham placed third for the most individual; and Walter Neitzke won fourth for the most extensive display.

On Christmas Day, the St. Louis Leader noted that the St. Louis Knights of Pythias Lodge Number 49 held a dinner for 86 children in the lodge quarters above city hall. Following the dinner, each child received a free theatre ticket and a sack of candy from Santa Claus. The lodge put on the entire program and dinner.

“A Nation in an Undeclared War?”

That was what a column in the Alma Record-Alma Journal declared in early January. “We are at war without having declared war” with Nazi Germany, claimed the columnist, by helping Great Britain, and that “the die is cast.” When will war be declared and by whom? In response to concerns that America would soon be involved in a war, President Roosevelt called up America to be “the great arsenal of democracy” and to prepare to defend the nation as Nazism threatened the entire globe. The race to help Great Britain, according to President Roosevelt, had to include the construction and export of more planes, ships, guns, and freighters.

Across Gratiot County, the tone of speeches and presentations also implied that war was not far off. Professor Ray Hamilton of Alma College described Nazi Germany as having a pagan government as he spoke to the Ithaca Rotary Club. Hamilton also said that a former Alma College professor was now being investigated for un-American activities. Other voices, formerly from outside the United States, warned the county about Imperial Japan’s status and actions. Dr. K. Ping spoke to the Alma Rotary Club about why he believed the Japanese would ultimately be defeated, in part because they took over too much of China and could not control it. Ping also stated that both the Communist and Nationalist Chinese had put aside their own differences to unite to fight the Japanese. Doctor Elmer Boyer, recently from Korea, gave a pair of talks in Alma about the harsh life under Japanese rule. As Christianity grew in Korea, the Japanese were very oppressive toward Koreans and extremely distrustful of all Americans.

The Gratiot County Draft Board invited men to volunteer early and join the Army or Navy, even as nineteen men made up the January quota and prepared to leave for Saginaw. Among them were Carl Deline, Herbert Wolford, and William Keon, all of St. Louis. As men were called, the Draft Board realized it would soon be interviewing men who were not volunteers. Members of the board, such as Lyle Whittier, attended meetings, including the one at the Alma Rotary Club, to explain the examination and classification process for the next 14 men to be called in February. Already, Alma lost some of its young men, like Captain H.L. Freeman, who headed the National Guard in Alma and who had been called to Fort Custer.

In other events related to the theme of war, the Redman Trailer Company of Alma became one of eight businesses nationwide approached by the government to build house trailers capable of holding eight bunks for soldiers. Such a contract meant that the Alma Company would need to expand its plant and employ day and night shift workers. A letter from David Glass, Alma College graduate, arrived home explaining his training with the aviation corps at Pensacola, Florida. A total of 976 aliens had registered in Gratiot County by the late December deadline. Ithaca postmaster James O. Peet announced that 415 aliens appeared to register as required by law. Many of those registered were of “foreign extraction” who worked in the sugar beet and farm fields. In other words, they were migrant workers. The Greek Relief Fund in Alma continued to grow from donations. By mid-January, the fund had raised $831.94 to buy supplies for the relief of the families of Greek soldiers who died as a result of fighting Italy. Over 500 local communities across the United States organized Greek relief funds. In Alma, James Stamas, George Goutis, and James Stavros formed the committee. The Alma Record openly endorsed the relief and asked readers to do the same. Doctor and Mrs. B.N. Robinson of Alma received word that Mrs. Robinson’s parents were safe and living in Southern France. It was the first word they had had of the parents since the Nazi invasion in June. The DeWachters formerly resided in Paris and had evacuated from the city. Word reached Alma through American citizens who met the DeWachters in Biarritz.

Life in the Great Depression/New Deal Programs

During the winter of 1941, the National Youth Administration sought to expand its work in Gratiot County by providing young people with work experience through gainful activities. One of these events involved planning the Alma Ice Carnival on Saturday, February 1. Several NYA boys worked as a crew to get an arena ready on the Pine River. The boys sought to create a track almost 300 feet long for various events, including speed skating, sled events, and several novelty events to take place that afternoon.

Alma Schools embraced the idea of using the old Washington School for classes that could enroll up to 100 young people. By offering woodworking classes for boys and home economics for girls, this NYA program dovetailed with the idea of preparing young people for the national defense program. As such, the federal government would cover almost all the expenses associated with ten-week classes that ran for eight hours a week. A.C. Heying would oversee shop work there while Mrs. Marvin Utter would have charge of the home economics classes.

The Works Progress Administration and the St. Louis City Council discussed spring work projects for eight city blocks, including curbs, gutters, and storm sewers. It would cost St. Louis $12,386, but the WPA covered $8,112 of the amount. Areas around North Pine, Washington, Mill, and Center streets were targeted. At the same meeting, city clerk Frank Housel told the city council that 15 able-bodied men owed the county labor on the roads, which amounted to $2 per day. This “work or no relief” policy in the county emerged earlier in 1940. On a lighter WPA note, Darrell Milstead, County WPA recreation director, said the WPA was testing a “toy lending library” at the Republic School recreation center. In this program, a boy or girl would check out a toy for up to two weeks, then return it to the school. If no one was waiting for the toy, the boy or girl could check it out again.

The Long Arm of the Law

During December 1940, 46 people were convicted of crimes, bringing in $222.75 in fines and $232.80 in costs. Three people were sent to Jackson prison and three to the county jail. A number of the court appearances involved game law violations such as carrying a loaded shotgun in a vehicle, violating the Horton’s Trespass Law, or transporting dressed venison. William Batten, 21, of Detroit, and Charles Van Atter, 31, of Eaton Rapids, stood mute to stealing a calf from the George Bates farm during the past summer. Batten got a $25 fine and costs, or 30 days in jail (where he initially went), and Van Atter went to prison on a $200 bond default. The two men picked up the Bates calf, which stood near the edge of the road, and made off with it. There was no word on what had happened to the calf.

Three area men were arrested, and more details emerged about the February 1939 break-in at the Lobdell-Emery plant, where 960 pounds of Downmetal and scrap aluminum were stolen. Arrests of Carl Baker, formerly of Alma, Charles Langin of St. Louis, and Charles Thompson of Alma meant more appearances in front of Justice Howard Potter in Ithaca. Baker had been the key suspect in the cases and was finally apprehended in Kalamazoo. The other men denied knowledge of the crime and requested an examination. This 1939 crime amounted to $100 worth of stolen metals.

Other various crimes and situations made the January newspapers. Russell Smith, Alma’s “heating engineer,” again caused trouble for officers and appeared in court on pretenses for not completing heating repairs. Smith had still not paid his nearly $10 fine for court costs. Hazel Ellsworth remained lodged in the county jail on charges of arson. Ellsworth appeared to be off her hunger strike, but continual attempts to harm herself meant she was under constant watch by a jail matron. Norman Skaggs, 22, of Cheboygan, appeared in court and pleaded guilty to starting a December 1939 fire on the Clarence Clark farm, three miles south of Alma. Skaggs claimed he started the fire while Clark was away, all on a whim. Skaggs hoped he might gain more work by rebuilding a barn to better support his wife and child. Skaggs left the area after the fire and could not make it on being paid five cents a bushel for husking corn. Skaggs now made a complete confession, asked for his punishment, and wanted to clear the matter.

The biggest news of the month concerned a strike by sixteen drivers at the Kress and Son trucking operation in Grand Rapids, which transported Midwest Refineries’ products. When replacements were hired for the striking drivers, several Kress and Son trucks were stopped in Alma and south of Ithaca. When a group of five men stopped a car south of Ithaca and told the driver he had better leave for his own good, the driver walked to the sheriff’s office and filed a complaint. In another instance, one Kress truck was sabotaged while enroute from Owosso. The A.F. of L. union called for the strike, and later that month, fifteen men appeared in court, charged with infringements against Kress Trucking. All seemed to have attorneys supported by the union, and they were released on bonds ranging from $250 to $ 1,000 each. Later, Roland Reitz, 45, of Saginaw, received a $50 fine and $60 in costs for his involvement in a truck holdup in Alma. The sheriff’s department called in special deputies and the Alma Police Department to address a strike situation.

Gratiot Farmers and the Winter

The snow was deep, and the weather was cold, but Gratiot farmers turned out for different programs to get them thinking about the 1941 farming season. The St. Louis Beet Growers Association held its 10th annual program at St. Louis High School and was impressed by the 1,100 people who attended – well above the anticipated number. International Harvester had a meeting for forty dealers at the Park Hotel in St. Louis, with luncheon served in the main dining room. Adolph and Henry Schnepp organized the meeting’s program. The St. Louis Co-operative Association held the city’s second big program of the winter, also at St. Louis, and planned to offer a tour of the new $50,000 creamery on North Mill Street. A group of 500 farmers and wives was anticipated for the February 1 assembly.

In other farming-related news, Breckenridge offered a 10-week adult education course in agriculture. It started on January 15 and was held on Tuesday evenings. Frank Longnecker of Vestaburg made the county newspapers when he announced that one of his pullets laid two oversized eggs in one month. The latest measured 6 ½ and 8 ¾ in circumference and weighed six ounces. A rabid skunk attacked Robert Monroe’s heifer southeast of St. Louis. Monroe saw the skunk bite the heifer on the head, then killed the skunk. The head was then sent to Doctor Frank Erwin, who had it analyzed in Lansing. The skunk was positive for rabies, and Monroe was told to give his heifer a series of shots to save the animal. He also watched the rest of his herd for fear that other rabid animals had attacked and bitten them.

Health Matters

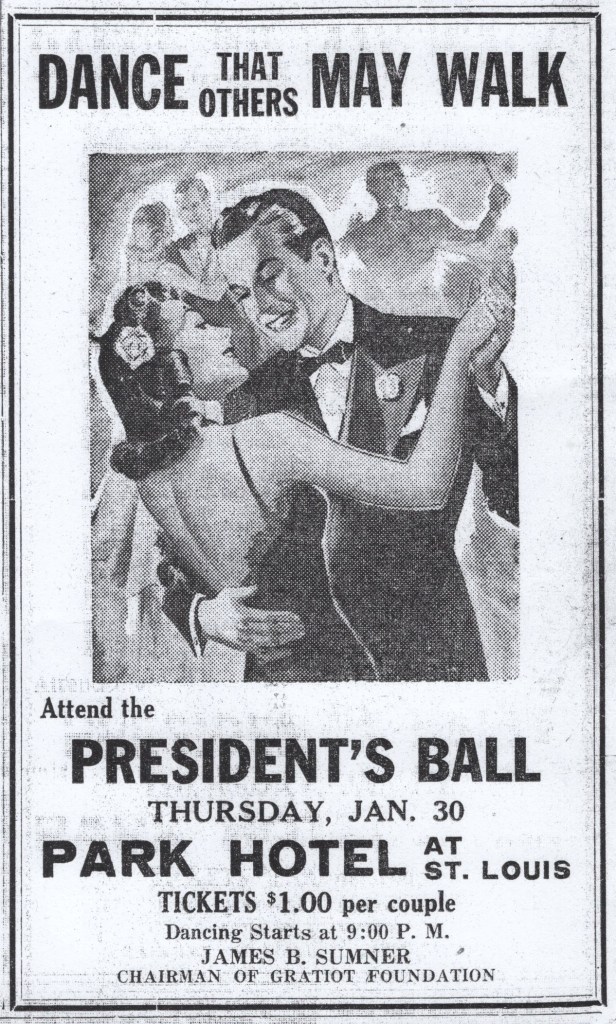

Much of the Gratiot news about health in January centered on infantile paralysis. During the Depression, the annual President’s Benefit Ball took place in St. Louis on January 30 at the Park Hotel to raise money to combat the disease. As a result of recent fundraising, the Gratiot County Chapter of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis supported seven cases without making the recipients’ names public. As of January 1941, the group had $300 in its balance and hoped to raise more money through the President’s Ball to support those who needed braces, special shoes, or appliances. Tickets for the ball went on sale, and members were asked to fill coin collection boxes and folders that held $2 each in dimes. Vere Nunn, cashier at Commercial Savings Bank in St. Louis, served as treasurer of the chapter.

Still, other people and events related to health matters were tied to Gratiot County. Two people who were x-rayed at a recent Michigan Tuberculosis Association clinic in the county faced immediate hospitalization. A total of 39 people attended the clinic; 25 of them had been x-rayed before. Of that group, two were deemed active, three were suspect active, and five healed of tuberculosis.

A wave of influenza hit Alma Public Schools hard, with four teachers out and fifteen percent of the student body absent on one day. By mid-January, local doctors believed that the worst of the flu had passed. William Lator, an Ashley High School sophomore, was in critical condition at Smith Memorial Hospital with blood poisoning. Lator had been sick for two months after receiving a scratch or prick while working in the woods. After admission, he improved slightly after a blood transfusion. Two-year-old Alfred Roberts of Middleton also nursed an infected arm. When his mother left the little fellow alone for a moment, she found him caught in the wringer. The rollers caused nasty wounds and required seventeen stitches to close, and then became very uncomfortable due to inflammation. This toddler also fell into a bucket of boiling water a year earlier, then later drank kerosene. Needless to say, young Alfred had seen more than his share of troubles. Another sad Middleton story involved the discovery of Charles Luscher, 69, who was found frozen to death in a ditch southeast of Middleton. He had been there approximately 2 ½ days and was found carrying bottles of beer and some meat, only two rods from his shack. Another sad story took place near Sumner, where Melvin Blackburn was found in a snowbank on the Ben Humphrey farm. Little hope of recovery was given due to prolonged exposure to cold weather and snow.

And So We Do Not Forget

Basketball games between two Fulton teams and Fulton alumni took place before New Year’s. In both cases, the alumni won: the girls’ alumni defeated the Fulton girls 26-16, and the boys’ alumni defeated the Fulton boys 28-23…The Gratiot-Clinton Bar Association feted Circuit Court Judge Kelly S. Searl by having a dinner in his honor at the St. Louis Park Hotel. A collection of approximately 175 circuit court judges, lawyers, and friends attended the dinner…Seventeen people enrolled in citizen classes at St. Louis High School on Monday nights. Three in the group took a course on “English for Newer Americans” led by Grace Niggeman. Some of the students included Anna Sabatavich, Mary Yanik, Anna Simonovic, and Cyril Sedlacek…The city play “Womanless Wedding” was again a big hit at St. Louis High School under the direction of the St. Louis Lions Club. John Brown starred as the bride and Doctor T.D. Gilson is the groom. Proceeds went to the Sight Conservation and Health Welfare fund of the Lions Club.

The final cost of the new county road garage outside Ithaca was $53,871.73 and was primarily funded by state funds. A complete financial report appeared in the St. Louis Leader…A group of 153 people in Porter Royalty Pool, Incorporated, found themselves dividing oil royalties after the state Supreme Court ruled on a case dating back to 1933. In a unanimous decision, the court dismissed charges by Glenn and Mildred Hathaway and 24 others, thus releasing the money…The Kroger Grocery and Baking Company moved to a new location on Mill Street early in 1940 and introduced self-service, which many customers liked. Oren L. Boyd worked as a manager and appeared in the newspaper…A wet, soggy snow left six inches in Gratiot County on Sunday, December 29, and lasted into the evening. It took workers in places like St. Louis most of the night to clear enough roads and streets for people to get around the next day.

A group of 400 people attended the annual stockholders meeting of the Redman Wholesale Grocery Company in Alma. The meeting took place at the Alma Methodist Church, which offered the group a free meal and entertainment after listening to financial reports and the election of officers…Two different groups of Alma people headed to Mexico for a few weeks to avoid the Gratiot County winter. Lester Welch, assistant manager at Martins, led a group of tourists to Durango, Monterey, and Mexico City. James Clark, JC Penney assistant manager, took his family on a three-week trip to Mexico…Temperatures in Alma on January 13 dropped to zero, but rose to 18 degrees above two days later…Alma’s ice rinks opened after the freeze south of the State Street bridge and on one above the dam. Snow had been removed to allow skating there, and it proved very popular with skaters…Cupid’s arrow struck Maynard Peackock, 23, of St. Louis, and Bertha Dickens, 22, of Alma as they tied the knot.

The Gratiot County Herald checked up on the 1940 winners of the baby contest. One year later, Judith Joan Russell, Elm Hall, Lee Arnold Cowles of Alma, and David William Seaman, also of Alma, all had their photographs and biographies as one-year-olds on the front page…The winner of the 1941 Baby Contest went to Raymond Kennedy, Jr., son of Mr and Mrs. Raymond Kennedy of Alma. He appeared at 2:56 a.m. at Carney-Wilcox Hospital and weighed 8 ½ pounds…Doctor Lewis Berg, psychiatrist, sociologist, lecturer, and columnist, spoke during the Town Hall Series at Ithaca High School gymnasium on “The Successful Personality.” Rotary clubs from around Gratiot County sponsored the presentation…One of the Detroit Tigers’ “G-Men,” Charley Gehringer, was the first Detroit Tiger to sign a 1941 contract…Jay Stahl of Ithaca received the Ballard Trophy at Ithaca High School for his football season, as well as being the team captain…A collection of former Ithaca High School football players from the 1906 to 1909 championship teams showed up for the all-sports banquet sponsored by the Ithaca Chamber of Commerce to honor Coach Steve Keglovitz.

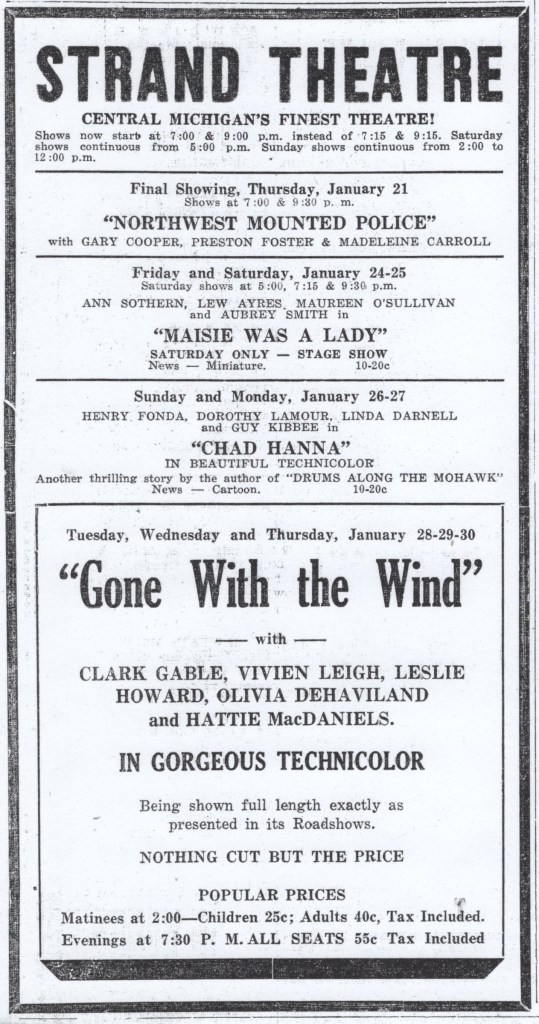

”Gone with the Wind” for the second time reappeared at the Strand Theatre in Alma for three dates on January 28-30. Evening tickets cost 55 cents, and one showing took place at 7:30 pm… George Gates took over the location of “Bill’s Popcorn Stand” in Alma on the Masonic property south of the Consumers Power Company building on South State Street. Gates now mainly sold apples and sweet cider…Ben East, wildlife lecturer and writer, appeared at Alma High School on January 14 to show moving pictures on “Islands of the Inland Seas.” The Gratiot County Conservation League supported the presentation…Mrs. Rebecca Louise Stevens, age 107, and the former wife of Dr. L. S. Stevens in Alma, passed away in San Diego, California. Doctor Stevens passed in 1899 and was buried in Riverside Cemetery…Lem Rowley of the Rowley and Church gas station in St. Louis did a neighborly thing for a person in need. Walter Gibbs lost his two Irish Setters and had little hope for their coming home. When neighbor Don Keane heard noises in his father’s barn a week later, he found the two dogs in a holding box, in poor shape and worn out. When called upon by Keane, Lem Rowley helped find the rightful owners of the two setters. Needless to say, Walter Gibbs was thrilled and grateful for the return of his two dogs.

And that was Gratiot County during the Depression and the War in January 1941.

Copyright 2026 James M. Goodspeed