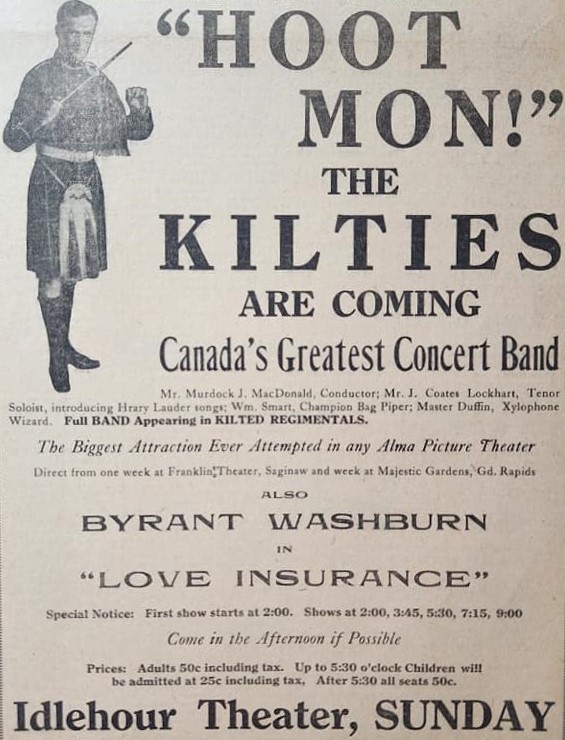

Above: An actual photo of the S.S. City of Alma taken in the 1920s; this postcard, supposedly of the ship, was issued with the ship’s name painted on the hull; Esther Rhodes, the daughter of a prominent Alma businessman, christened the ship at a ceremony in 1920.

Sixteen-year-old Esther Rhodes of Alma stepped up on the platform adjoining the ship’s top. Freshly painted battleship grey, the vessel was draped in many flags and streamers. Miss Rhodes then broke a bottle on the ship’s hull and pronounced, “I christen thee City of Alma.” Amid the cheering of the small crowd, the boat slowly slid into the water. With the christening, the group celebrated the culmination of a successful post-World War I war bond drive in Alma.

During the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive in late 1918, Alma earned recognition as one of Michigan’s largest purchasers of Liberty Bonds. Over eighty percent of the people in Alma bought a bond – a record for cities buying $10,000 or less in bonds. By raising over $403,000, Alma led Gratiot County in its effort to raise over $1,000,000 for the war effort that fall. Most of the time, Michigan towns and cities with successful bond drives had tanks named in their honor. After the war ended, the government turned to naming ships in honor of places for their work with bond sales.

On January 20, 1920, at 9:15 AM, nine people went down to the Bristol, Pennsylvania pier. Charles G. Rhodes, his wife, and daughter accompanied Alma’s Mayor Murphy and his wife. Rhodes was a prominent Alma businessman and was vice president and spokesman for the Republic Truck Factory. Two men who helped lead Alma’s successful Liberty Loan Drive, Lieutenant T.A. Robinson and Lieutenant D. Sullivan, also attended. Three people from United States Emergency Fleet Corporation offices also went along.

The ceremony to launch a ship took place at the Merchant Shipbuilding Corporation. Ten boats, in different stages of construction, could all be seen—one of them, the S.S. City of Alma was 417 feet long and 54 feet wide and belonged in the 9000-tonnage class. Onboard, it had “palatial quarters” for its ship’s crew and officers. A fabricated type of ship, it had rolled plates in the hull. These plates had holes punched into them at steel mills hundreds of miles away, a result of a type of production that sped up the building of ships during the war. This ship also had 3000 horsepower and burned oil on three boilers, but it could be converted to coal if necessary.

Still, during the Alma visit, the new vessel was unfinished and would not be ready for several weeks. Despite the delay, the Alma group received a tour aboard a similar ship in the naval yard, and a set of the S.S City of Alma’s blueprints and official ceremony photos went to Alma City Hall for display. When it became seaworthy, the new ship was assigned to the United States Shipping Board and then to the American Steamship Line. The vessel eventually belonged to the Waterman Steamship Company in Mobile, Alabama, during World War II, even though the United States Maritime Commission controlled the boat through a charter.

However, the story of the ship had a tragic ending. On June 3, 1942, while carrying 7400 tons of manganese ore and 400 miles northeast of Puerto Rico, a German submarine, U-172, sank it with one torpedo. The ship sank within three minutes, and 29 out of 39 men aboard died. The ten remaining crew members floated in a lifeboat for four days before being rescued.

Sadly, after 22 years of service, the S.S. City of Alma went to the bottom of the Caribbean.

Copyright 2024 James M. Goodspeed