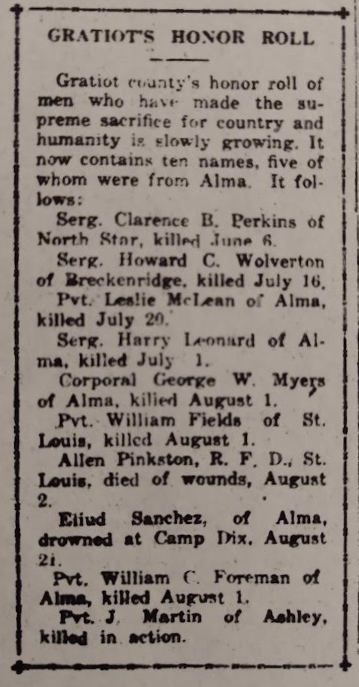

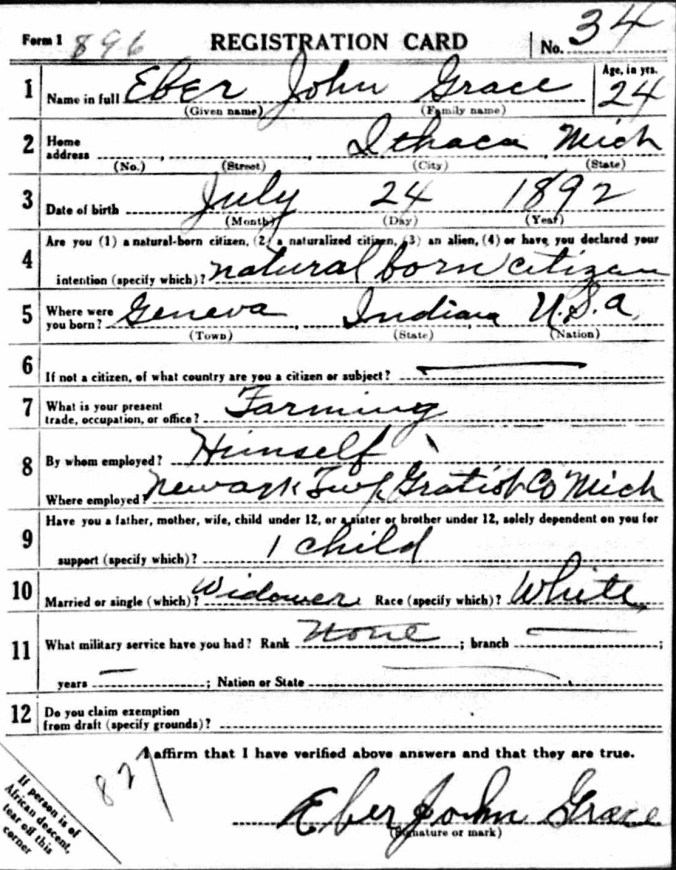

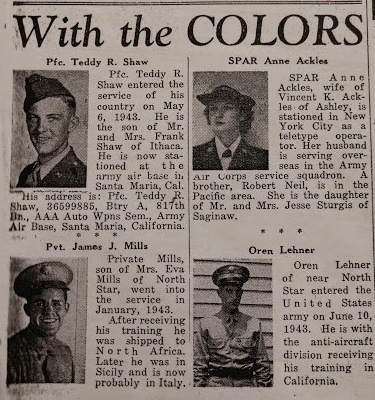

Above: Girls from Alma High School dehydrate eggs for the Armed Forces while working after school at Swift & Company in Alma; a group of farmers in Lafayette Township basks in the milder than usual March 1944 weather; notices of servicemen from the March 9, 1944 issue of the Gratiot County Herald.

It was March 1944, and an early spring reached Gratiot County, Michigan. Farmers were at work in their fields, and they heard the government’s call to grow more crops in 1944 for the war effort. Still, many wondered if they could harvest all that they were being asked to plant.

Amidst the stories of those Gratiot County men and women abroad was the reality that some would not be coming back home. There seemed to be the seeds of growing optimism that the United States and its Allies had turned a corner against the Axis. However, the war was far from being home, and people in Gratiot County again realized that it would be a long road to victory.

Farming

As March began, the need for more farm laborers for the upcoming summer was very much on the minds of area farmers. Leaders of the Gratiot County Youth Labor Committee were called to the courthouse in Ithaca to prepare for the 1944 crop season. Discussions took place about getting more youths to work on farms. Superintendents of area schools and agriculture teachers made up lists of boys and girls who would be asked to volunteer their time to work.

Gratiot County’s farm commodities had been making a difference in the war effort and had been shipped to different parts of the world. Creamery butter, dried whole eggs, cheese, dried pea, and navy beans made up the list. St. Louis shipped over 223,000 pounds of creamery butter in 1943. Breckenridge had sent over 2.1 million pounds of navy beans. Alma led the county with its 80,000 pounds of American cheese. The War Food Administration pushed the importance of raising more food in 1944 as the Lend-Lease Program needed it. Even in places like Alma, which raised 11,300 bags of dry beans, the government wanted more.

To encourage Gratiot County farmers to raise more food, the AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Administration) held a farmer’s rally at the Ithaca High School gymnasium. A special guest speaker, Duncan Moore, a well-known radio announcer, spoke to the farmers about the need for more massive crop production in 1944. The rally took place following a concert by the Ithaca High School band, poetry readings and vocals by high school students.

Victory Gardeners in St. Louis were asked to combine orders for seeds, but to only order what would be used. The Strand Theatre was the location for the annual meeting of the Alma Beet Growers Association, following a dinner and election of officers. The government repeatedly encouraged county farmers to sign up for more sugar beets. Because of the need for home use, as well as making alcohol for explosive and synthetic rubber, Gratiot County was asked to grow double the 1943 amount, which had been 64,232 acres. Still, many county farmers could never remember a more uncertain time to raise beets. Because the progress of the war had been slow, and that there had been a lack of labor, they feared that the increased crops would go to waste. Also, gasoline for tractors was a concern, as well as getting machinery repair parts, overall shortages of machinery, and most of all there was Gratiot County’s weather.

As an incentive to persuade the farmers, new contracts offered $13 per ton of beets. However, the farmers remained wary of the lack of farm help to work the beet fields. The government countered by saying that migratory labor would be available and these workers would stay in the county until all work was completed and the crops harvested. Beet farmers could also receive more significant consideration in obtaining draft deferments for needed farm workers for corn, beans, and the sugar beets.

Men and Women in the Service

A total of 38 men passed pre-induction exams and had to leave the county in March. The Army called men on March 16, and a total of 22 made up the group. The Navy took another 16 men on the next day. Among the Navy men inducted included Leo Aumaugher of Wheeler and Ernest Rozen of Ashley. Some of the Army inductees included Randal Stafford of St. Louis and Jack Lowry of Alma. The Gratiot County Draft Board had been told to speed up inductions in response to Michigan’s call for 300,000 more men for the service, as well as creating a significant reserve pool.

The news abounded with announcements and updates of Gratiot County’s men and women who had gone off to war and of those who served stateside. Miss Nola Blair of Middleton completed her work as a registered nurse and was being sent to Kentucky. Anne Ackles, whose husband was from Ashley and who served in the Army Air Corps in Europe, now served as a SPAR and teletype operator in New York City. Private James J. Mills of North Star had been shipped to North Africa, moved to Sicily and now was in Italy. Private Milton Rozen of Ashley entered the service in January 1943 and now trained at William Northern Field in Tullahoma, Tennessee. Lieutenant Robert H. Reed of Alma became a combat pilot after completing advanced flying school training. Major Frank W. Iseman became Lieutenant Colonel Iseman and was now the Director of Ground Training at Sioux City Army Air Base.

Word arrived that Lieutenant John W. Shong returned from combat missions as a torpedo bomber at Guadalcanal. After flying missions almost every other day early in that campaign, Shong now served as a flight instructor at Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He received a medal for meritorious achievement in fighting the Japanese. Lieutenant Frederick Rearick also was home after serving as a Marine at Guadalcanal and New Caledonia. Rearick spoke to groups in the county about what he had experienced in the Pacific war while in combat. Royal F. David, whose father was from Lafayette Township, had served for 21 months in New Guinea and had fought in the Battle of Buna with the 32nd Infantry Division. David spent several months in the hospital with malaria fever and then was discharged. Private Fred Hicks from St. Louis won the right to wear the Wings and boots of the 82nd Airborne after completing his fifth jump of the war at Sicily. Hicks would be involved with many decisive battles in the 82nd Airborne during the war. Brothers Russell and Glenn Sipe from Alma reunited in the Hawaiian Islands after not having seen each other in almost two years. Russell had been in the Navy since August 1942, and his brother served in the Army since March 1943. Other Gratiot County men like Captain Stewart McFadden, an Alma High School, and Alma College graduate, defended the United States in places like Panama. McFadden had been there for nineteen months he received a promotion in the Army Air Force.

Several of these servicemen and women wrote home about the war from Africa, Italy, and the Pacific. Charles Barden from Ithaca wrote to his parents, telling them of his challenges of traveling in India to find another Ithaca native, Frank Klein. Barden remarked that a few other servicemen tried to buy and resell fire opals in hopes of making money back home. Barden mailed a few of them back home for his parents to see. John Hoyt, a chaplain from St. Louis, told of his experiences from Africa. The poverty and inability to converse in different languages challenged him. Still, Hoyt remarked that “…I heard someone say that a soldier will get out of the army just what he puts into it.”

Across the county, stories regularly came in about how Gratiot County treated its sons and daughters at home. The Wheeler Methodist Church held a service where 200 people gathered to honor them. Reverend Kenneth McBryde presided over the ceremony in which he read the name of every man from the Wheeler area who was in the service. Of a total of 69 names, 63 of them had a family member present for this service. Twenty-seven of the men served overseas. The minister also lit four gold candles to represent the men who had died. These included: Donald Hartenburg, D.C. Furgason, and Gerald Steward, and a Lt. Lapino. Over at Elwell, a church added two stars to the fifty-two that already existed on the community service flag. The new stars represented Ramon Fink (Army Air Corps) and Wallace Humphrey (Marines). The George Myers American Legion Post in Alma initiated a large class of new members, including twenty men who now would be considered World War II veterans, all honorably discharged.

The hardest news in the county involved the growing list of those who died in the war. In early March, Ithaca and Ashley experienced shock with what they heard. Private D.C. Furgason was killed in Italy on the Anzio Beachhead on January 27 during the invasion. Furgason would be Ithaca’s first son to die in the war, and he was only nineteen years old. John Paksi of Ashley and Robert Parks from Alma both appeared in the news at the same time as Furgason’s death. Paksi and Parks had been reported as missing in action. Private Edgar Hitchcock of Pleasant Valley also died in Italy in early February. Arnold Riedel, a Breckenridge High School graduate, also died there while serving in the Infantry. Special services for Reidel took place at the Breckenridge Methodist Church soon after news of his death was confirmed. Gratiot families also were struck with the announcement of those deemed as missing in action. Mrs. George Lanshaw of Alma was told that her brother, Robert Wellman, had become missing in action on March 9 during a mission over Germany. In early February, Mrs. Lanshaw had just received a letter from Robert that he had completed fifteen missions over Germany and that he hoped to reach the lucky number of twenty-five so that he could come back home. Robert Wellman served as radio operator on a B-24 Liberator on a B-24, and he had been missing since a flight over Germany on March 9.

Red Cross Action

The Gratiot County Red Cross continued to serve and ask for the county’s support during March 1944. The organization proclaimed in the Gratiot County Herald, “THE RED CROSS IS HERE!” and that was in Gratiot County “ALL THE TIME.” A long list of achievements by volunteers educated the public about what the county unit had accomplished. Turtle neck sweaters, gloves, helmets, rifle mitts, socks, sweaters, navy scarfs, pieced lap covers, as well as civilian garments and surgical dressings – members of the Red Cross had done all of this. The upcoming War Fund Campaign was planned for the end of March, and a workers meeting took place in the courthouse in Ithaca. Mrs. Cecil Marr headed the St. Louis unit, and she reminded volunteers that they were entitled to wear their service pins if they had served enough time. She hoped that more eligible volunteers would wear the badges in public. The St. Louis chapter sought to raise its share of the $19,500 needed for the countywide drive. The chapter held a special dinner at the CSA Hall to do its part, which drew 250 people and aimed to raise money for the St. Louis quota of $2,600. Frank Housel, city chairman, announced that St. Louis also planned to hold two more benefit parties. One of them at the St. Joseph church raised $100 and then a Tag Dale sale on a Saturday brought in almost the same amount.

The three-day county campaign late that month succeeded beyond expectations. Every district reported raising more than their higher expected quota. People county wide gave more than $4,000 over the initial goal of $19,500. Gratiot County again proved that it cared about and supported the work and efforts of the Red Cross.

Rationing

Gratiot County residents continued to conserve resources for the war effort. The Gratiot County Road Commission in Ithaca became the location of a central truck tire inspection station. This site existed to make sure that drivers got the maximum mileage on their tires. A dealer committee made up of six men, headed by James Giles of Alma, re-inspected trucks and commercial vehicles of owners that wanted new tires. Those in Gratiot County who had gasoline ration books felt the pinch when they learned that they would experience a cut from their allowance of three gallons to two gallons of gas per week. The government continued to crack down on black market sales and coupon counterfeiters, who drained off an estimated 2.5 million gallons of gasoline every day in America. Smaller things that Gratiot people could do to help with the war included saving tin cans in St. Louis and taking them to the city highway garage and placing them in a particular bin.

When it came to food rationing, certain foods could only be purchased with Green Stamps, K, L, and M in Book Four through March 20. However, selected blue stamps would be good for processed foods through the end of May. Point reductions for pork and beef products took the public by surprise because the government believed that more would be available for the public in 1944. Good news also came with the announcement that homemakers would again be able to have 35 pounds of sugar for each of their family members. Any family that canned and preserved food could apply for a maximum of 250 pounds of sugar to use for canning. All that a person had to do was pick up an application form at the county rationing office in Ithaca and mail it to the Office of Price Administration. To entice farmers to grow sugar beets, they would receive another 25 pounds of sugar that came from their crops. The company with whom the farmer signed a contract would be the place that provided the sugar. No ration stamps would be required.

And so that we do not forget…

Postage rates would jump at the end of the month from six to eight cents for airmail…St. Louis played Fulton in the regional basketball tournament at Mt. Pleasant…The Bank of Ithaca warned residents that they needed to build their savings accounts with war bonds…Swift and Company needed fifty women for egg candling and breaking. No experience was necessary…The unusually mild winter allowed farmers to get into the fields very early in March. Men from the Tom Londry farm in Lafayette Township had their picture in the paper while preparing their fields…A diphtheria clinic took place for Alma children for treatment. An estimated 300 school children under the age of ten were believed to be at risk…St. Louis announced that it would move its clocks ahead one hour starting April 2. Other Gratiot communities were expected to follow; however, Saginaw had tried earlier in March to move the time forward but changed its minds and went back to War Time until April 2…St.Louis became the site of two different hitchhiking stations, one along the intersection of US-27 and M-46 at the Hi-Speed Service Station. A motorist saw signs that said that soldiers waiting there needed a ride. The other station would sit on the south side of the city near the city limits. Talk continued of placing a third station on the east side of town for soldiers who wanted to travel to Saginaw…Finally, there would be no liquor bonus during the April rationing period. However, rum, wine, and Vermouth remained unrationed.

So, that was March 1944 during World War II in Gratiot County.

Copyright 2019 James M Goodspeed