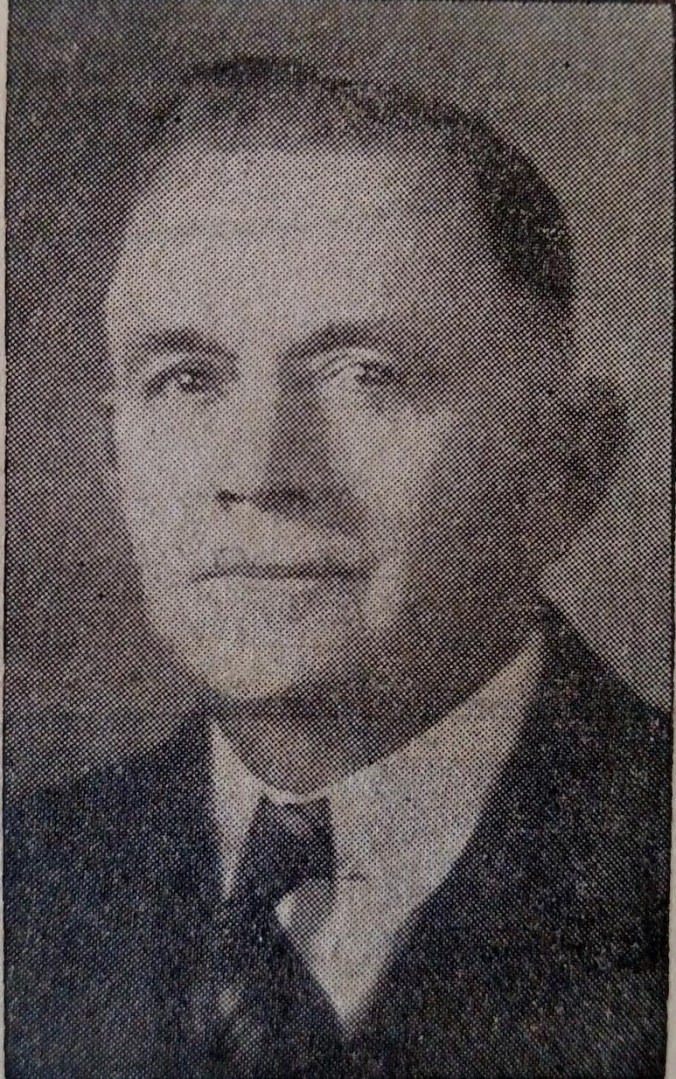

Above: 1918 photo of Leslie McLean; McLean’s plot in Riverside Cemetery in Alma; McLean’s identification medal; Army telegram to Ella McLean and card she wrote to the Army; other McLean marker in Riverside Cemetery.

He was just a boy with a shock of long black hair who begged his parents to let him get into the war. Today, he is the youngest of Gratiot County’s veterans who died in the World War. His name was Leslie C. McLean from Alma and his story is a difficult and intriguing one.

Leslie Clifford McLean’s story starts in 1902 when he was born to Edward and Ella McLean in Bethany Township on what was called the Boyd Farm. The McLeans worked hard to clear the land and put up all of the buildings on what was considered a pioneer farm. The family later moved to the Delbert Conley farm near Alma. Leslie’s father was a farmer and he had two brothers. Although news accounts through the years would say that there were three McLean children, it was decades later that a descendant of the McLean family told an interesting story about a very young Leslie who once brought home a young boy in need of food and clothing. Soon, Ed and Ella McLean took the boy in and raised him along with Leslie like a brother. Later after the war, Ella McLean would share her love for flowers and gardens with the communities where the family lived. Edward would work as a repairer at the Republic Truck Company in town. Prior to the start of the war, the McLeans moved to Alma and lived there for four years while Leslie attended Alma High School up until his enlistment.

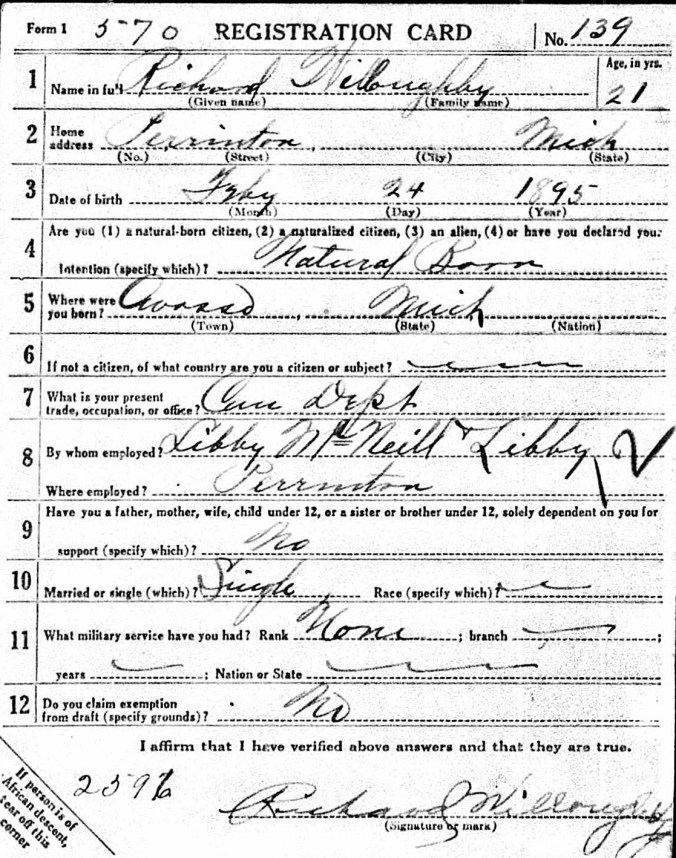

In 1918, young Leslie McLean desperately wanted to enter the war while he could. Three days after his sixteenth birthday, Ella McLean signed the papers that allowed Leslie to do so. How unusual was it for a boy, barely age sixteen, to fight in World War I? According to Army census records, the average age of a soldier during the war was over the age of twenty-four, and most soldiers were in the range of twenty to twenty-five years of age. There were indeed instances of “kids” who went off to war, but there was not a lot who did so. Fourteen-year-olds (a total of 16), fifteen-year-olds (140), and sixteen-year-olds (935) did serve the country. McLean was only one in less than one thousand who did so. Considering that the minimum age for enlistment in 1917 was eighteen (seventeen if one could get a parent’s permission), it is surprising that the Army took these volunteers. Yet, in a time of war, they did so. McLean must have been one of those youths who believed that the Great War was the most important event of their young lives, and they were determined to play a part in it.

Once young Leslie was in the Army there was not a lot to his story, however, some things are known prior to his death. He enlisted January 23, 1918, at the Alma recruiting office, but because his parents had moved to Midland in 1918, both Gratiot and Midland counties would count Leslie as one of their own. Leslie was sent to Camp Hancock, Georgia and arrived in France on April 7, 1918, with Company G of the 38th Infantry. It was thought that he was fighting in the trenches in May and that he saw several battles in July, which coincided with the Second Battle of the Marne. McLean wrote one letter home in June shortly before he was killed. “I am feeling fine and hope you are the same.” He asked for some news clippings from the Alma Record “as I would like a to get a little news of the town.” He then told about the reality of being on the front. “A few shells bursted near us yesterday, but not close enough to hurt anyone. We have been very lucky that way so far, but it is hard to tell when one will drop in the middle of us.” He explained the importance of having one’s own hole to avoid the blasts, even sleeping in them at night, however, they were damp. He thought that men in his unit slept quite well once they had obtained straw from a local farmer. His only regret was that they needed water, had not washed for two weeks and had only received two meals each day (one at ten o’clock in the morning and the other three o’clock in the afternoon). The men did receive a cup of coffee later in the evening. “We have had the same thing every meal now for over a week. We have some kind of French meat. It looks like horse meat and we have potatoes, bread, and coffee. Once in a while, we get a little rice or bread pudding without any sugar for dessert. “ With this closing, the letter contained the last recorded words that Leslie McLean shared with his family and Gratiot County. It would not be until a month after his death that his mother shared the letter with the public.

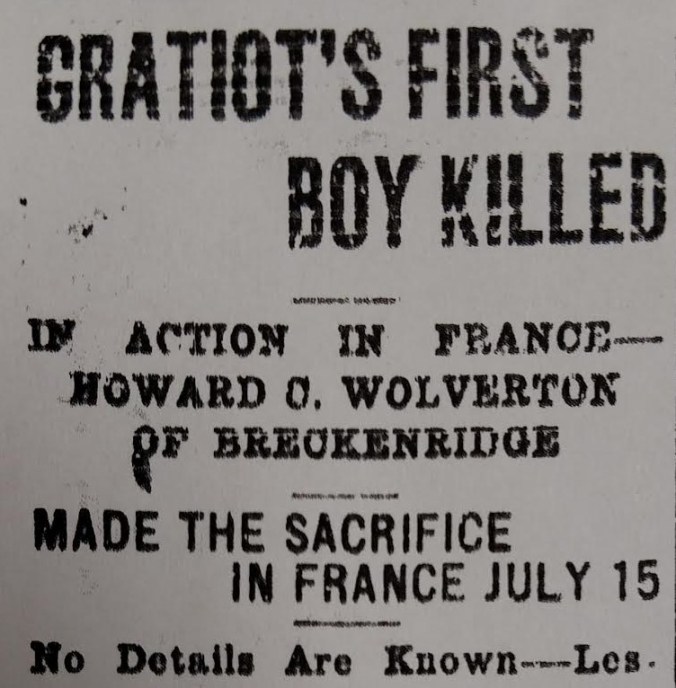

Leslie McLean’s death was first reported on August 1, 1918, even though he died earlier than this. The Alma Record reported that “The hand of grim death, which is stalking over the blood-drenched battlefields of Europe, has reached forth its bloody dripping fingers and called to its own the first Alma man to fall on the battlefield, facing the scourge of the earth, the terrible Hun. Leslie McLean is the first Alma man called.” A week later, the Midland Sun also reported on McLean’s death. The Sun noted that Ella McLean had been notified of her son’s death by telegram and that his parents were living in Midland. Prior to Leslie joining the Army, Edward McLean had opened a pool and billiard parlor in the city and young Leslie had spent several months there helping his father to set up the business. The Sun also noted that Leslie had given his mother’s name as his “nearest friend” and had taken out the maximum government insurance policy of $10,000.

When McLean’s death first became clear, it was announced that he died on July 20. Once the news reached Gratiot County there was an immediate desire to have a memorial service for him, even though his body was in France. At this time in Alma, a Chautauqua meeting was taking place and the tent was going to be used for the memorial service since the number of those expected to attend could not all fit into the McLean’s church, the Methodist Church of Alma. One of the key Chautauqua speakers, Captain George Frederick Campbell, a British flyer who had fought in the war, even promised to stay an extra night so that he could be a part of the program. Churches in Alma closed up that Sunday evening in a show of unity across denominational lines in order to pay tribute to McLean. The service also had ministers from different churches who spoke about McLean. The tent was full that evening as Alma mourned Leslie McLean. An estimated 1500 people attended the service.

In early September 1918, the story of Leslie McLean had what would be the first of many turns. Through all of these events, there was a family that waited for more information about their son’s death. At times these turns seemed cruel and unfair. The September 12 issue of the Midland Sun surprisingly featured an article that “Leslie C. McLean May be Alive.” Five days earlier, Ella McLean received a letter from Leslie’s commanding officer, Captain J. W. Woolridge, that he was recommending that Leslie be sent back home because “he had done his bit,” he had been wounded in a “desperate battle” on July 15 and Leslie was slightly wounded (the telegram was dated August 5, however, it took over a month to reach the McLeans). For Ed and Ella McLean and their family, their grief had just been turned to hope that their son was alive. On October 31 the Alma Record also reported that Leslie was alive and that he had only been wounded. Even the Detroit Free Press carried a small announcement about McLean. What had happened? The McLeans and the town of Alma had held a memorial service almost two months prior to this and now the first Alma man to be killed in the World War was said to be alive? The McLeans and many others were bewildered by this news.

Even more details about the death (or life) of Leslie McLean now started to filter into the press. Supposedly, he had been shot in the right thigh while fighting off a German attack near Metzy, France. Another telegram, dated September 21, told the McLeans that Leslie had survived, however, it was impossible to tell which hospital he had been sent to. The telegram also stated that the Army did not know if he was wounded, gassed or a victim of shell shock. Michigan Congressman G.A. Currie entered this story as he wanted an investigation into what had actually happened. Currie attempted to get more answers to the McLean mystery. Still, the investigation would linger another three months and the McLean family was left wondering what had happened to their son.

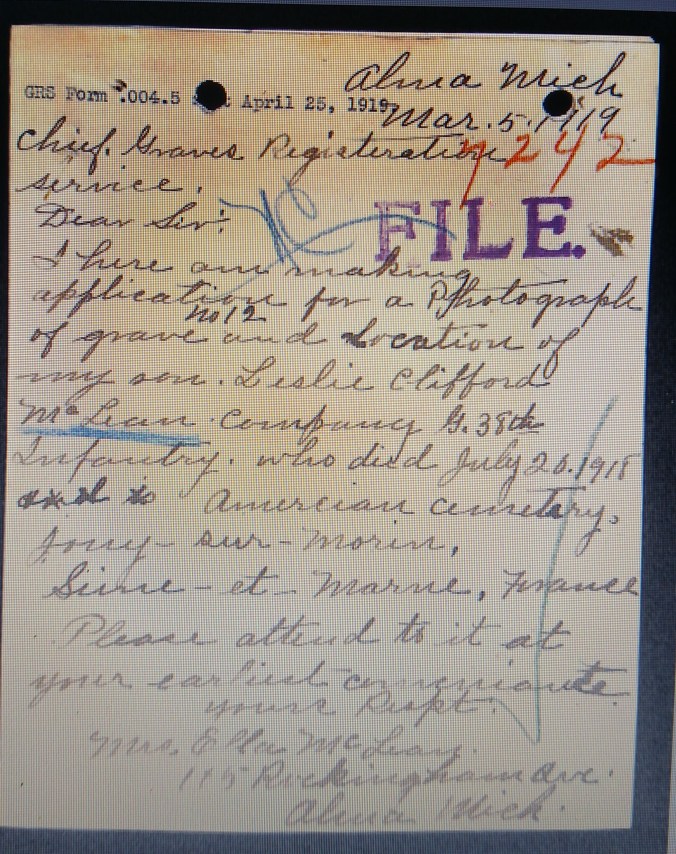

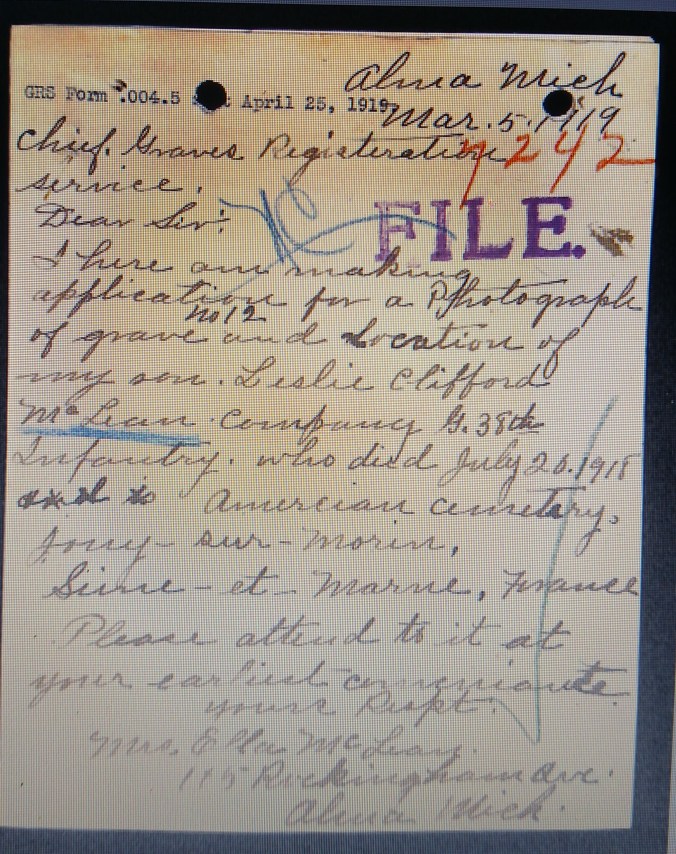

In early January 1919, with the war now over, news came that friends of Leslie McLean who were in the Army at the same time Leslie was believed that he was indeed dead. Even more, the first installment of the government insurance policy was paid to Ella McLean’s policy that Leslie took out in her name. Another sad event happened when in February, Colonel Charles C. Pierce of the Graves Registration Service in France sent word to the McLeans that their son was “in a hero’s grave in the American cemetery at Jouy-sur-Moin, Seine-et-Marne.” The Alma Record also wrote that Ella McLean received a letter prior to this one that a St. Louis soldier told of meeting another St. Louis man in France who witnessed a wounded Leslie McLean on July 15, 1918, who was crawling to a first aid station “after having refused assistance” for help. He claimed that McLean died from blood loss due to his wounds. For the first time the press now openly addressed the mix-ups, delays and crossed messages that played a part in determining what really happened to young Leslie McLean. This was also the first mention that Leslie had been to a field hospital.

In all of the confusion and renewed hope that her son was alive, Ella McLean returned the first insurance checks issued to her upon the hope that her son was not dead. No further checks came to her. For the remainder of 1919 and most of 1920, Ella McClain and her family lived with the uncertainty of their son’s death or existence. Burgess Iseman, who was a former soldier from St. Louis, wrote to the Quartermaster General in Washington and asked where Leslie McLean was buried so that he could visit the grave. The Army wrote back and told Iseman that McLean was in grave #52 in the American Cemetery in Jouy-Sur-Morin. It is unclear if Iseman made it there or not, but at least there were others who were interested in keeping the memory of Leslie McLean alive. In December 1920 the story took another turn. The Alma Record ran an article on December 30 that read, “PREY ON GOLD STAR MOTHERS: Crooks Attempt to Secure Funds by Sending Fake Reports by Telegraph, LOCAL WOMAN NEAR VICTIM.” It stated that “Mrs. Edward McLean is suffering from the heartaches of the noble mother who has given her son for the honor of her country.” Ella received a telegram that read, “Arrived today. Coming home. Wire $100.” It was signed Leslie McLean and it was sent from Brooklyn, New York. Was it possible that Leslie McLean was alive 2 ½ years after his death was first announced? Ella sent her son Herbert from Midland to Brooklyn, New York to find out who sent the telegram. Four days later she received a telegram that “The man is a faker” and that the first telegram was a hoax. Fate was again playing with the family’s emotions.

It would not be until the summer of 1921 that some closure came to the McLean family. It was then that someone answered an article in the American Legion magazine regarding what happened to Leslie McLean. A Corporal Orman Egleston, who was from Oswego County, New York, had served with Company G of the 138th Infantry, along with Leslie. He wrote to Ella McLean and detailed her son’s last days. On July 15, 1918, Leslie had been wounded across both of his legs and he was placed in the cellar of a hotel in Merzy, France. Egleston was in the cellar with McLean and a Frenchman. All three had been seriously wounded. Anyone in the cellar was told that if anyone could walk they were told to get up and leave with the retreating American troops as the Germans were soon to surround the town. After two or three days, the Frenchman crawled out of the cellar and a scream was heard shortly afterward. It was believed that the Germans had killed him. With little to eat or drink and seriously wounded, McLean and Egleston were in the cellar until July 20, a total of five days. It was then that Egleston decided that he would crawl out, which he did. After crawling to his former headquarters in the town, he passed out. Although the Germans soon discovered Egleston, they did not kill him. The Germans soon left the town and Egleston was somehow reunited with his commanding officer. He told the officer about McLean being in the basement and a search party found him. However, after being evacuated, McLean died on his way to the hospital. This testimony was now the concluding piece of the story of how Leslie McLean actually died.

After years of grief, discouragement, hope and false hope, it was during the summer of 1921 that things happened that allowed Leslie McLean to return to Gratiot County. Ella McLean had made it clear that ultimately she wanted her son to buried in Alma and not remain in a national cemetery in France. The Army exhumed the remains and upon a final autopsy in 1921 it was noted that although there was not a lot to identify Leslie beyond his dental records. However, it was recorded that his hair was “apparently black and plentiful.” Several times the records stated “DWRIA” which meant “Died of Wounds Received In Action.”

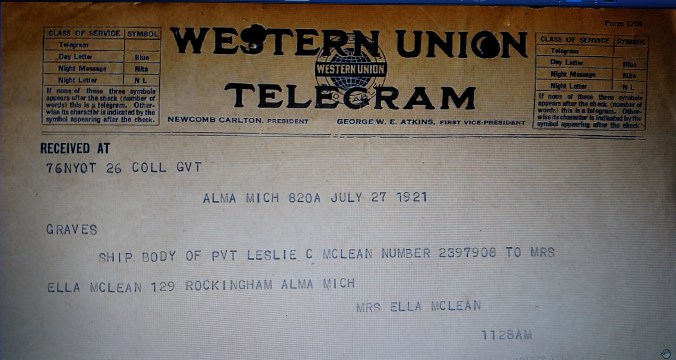

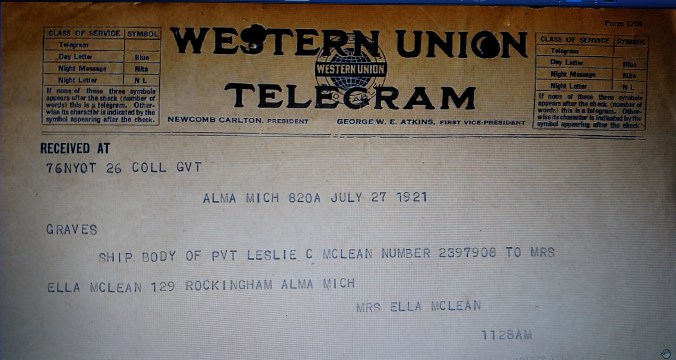

On July 2, 1921, the body of Leslie McLean started home aboard the SS Wheaton. He ended up being one of 45 men from this group to return to Michigan that summer. On July 27, the McLeans received a telegram telling them that Leslie’s remains would be delivered to them on July 27. The journey led to Alma and the McLean family held the funeral on Sunday, August 4 at the Alma First Methodist Episcopal Church. It turned out that another Alma man, Sergeant Harry Leonard, who also had been killed in July 1918, was also being brought home on the same transport with Leslie McLean. There were two World War funerals on the same day in Alma – and both were held at almost the same time, but at different churches. Both men were buried in Alma’s Riverside Cemetery and hundreds turned out for the two funerals. This was the second Alma funeral for Leslie McLean and people still came to pay their respects. The McLean family now had closure to the tragic death of their youngest son.

As time passed the memory of Leslie McLean’s name appeared again. In March 1934 the Gratiot VFW Post in Alma was named in honor of him. Forty veterans attended the meeting and twenty-two signed the post’s charter that night. On September 10, 1937, Ella McLean passed away. In response to her youngest son’s death, Ella was made an honorary member of the VFW and American Legion, as well as an active member of the American Legion Auxilary. At her funeral, an American flag was placed on her casket. Her obituary also told more about her. After the moves back and forth from Midland to Alma (apparently during or just after the war), Edward and Ella purchased a home on Rockingham Avenue which was in a way a living memorial to their son. They created a beautiful garden which the town of Alma knew about because of its flowers. Ella grew tulips, gladioli, delphinium and perennials which decorated their garden. They often entered them in flower shows and they also created a business that sold flowers and bulbs. Ella would frequently take gladiolas to downtown Alma businesses for their display windows. When she passed, it was said that she was remembered as “a remarkable but modest personality.” Edward McLean lived until September 30, 1942. His funeral, like his wife’s, was held in the family home.

In the early 1920s, a call went out to ask Gratiot County’s World War I veterans to share information for posterity regarding their service. Leslie McLean’s file was basically empty, containing only an article from the Lansing State Journal published after the war about his death in a French cellar. That was all that it said. Not even his service serial number was listed (it was identified later as #2397908). When the Alma VFW Post dedicated its new building on May 12, 1973, on Wright Avenue in Alma Leslie McLean’s story was told again. Mr. and Mrs. Clare McLean of rural St. Louis, relatives of Leslie McLean, donated McLean’s picture and a clipping about him from the 1918 Alma Record. After the end of the Vietnam War, this brought the story of Leslie McLean to another generation of Gratiot County residents.

Yet, McLean’s story came up again. In 2014, the Alma Public Library sponsored a program entitled “Remember Me – A Walking Tour Through Alma’s Riverside Cemetery.” Local historian Dave McMacken wrote the script that introduced several interesting and important people from Alma who were buried in Riverside Cemetery to those who wanted to learn about Riverside Cemetery. Those who went on the trip to the library and the cemetery to learn these stories heard McMacken tell the background of certain individuals who featured in the tour. A local person dressed, read and acted out the part of the deceased. One of the stories featured Leslie McLean, who was portrayed by Ithaca High School student Dustin George. Finally, during the 2017 fall semester, a Fulton High School junior who was looking for a research paper topic relating to Gratiot County’s history came upon the story of Leslie McLean. She wanted to learn more about him. Brittany Barrus sought out McLean’s grave, searched through old newspapers and wrote a research paper about him.

Now it has been a century since the service and death of one of Gratiot County’s most interesting and tragic stories concerning about men who died during the Great War. The boy with the shock of long, black hair, Leslie C. McLean of Alma, was one of these men. And he was only sixteen years old when died in France in 1918.

Copyright 2018 James M Goodspeed

Above: news advertisements from the Gratiot County Herald and Alma Record from July, 1918.

Above: news advertisements from the Gratiot County Herald and Alma Record from July, 1918.

Above: American Protective League newsletter, and badges. The membership card belonged to George Herbert Walker from St. Louis, Michigan.

Above: American Protective League newsletter, and badges. The membership card belonged to George Herbert Walker from St. Louis, Michigan.