Above: a host of advertisements from Gratiot County newspapers from March 1918.

In March 1918 many people continued to make wartime sacrifices as winter ended. The Great War affected every American from big cities to small towns. Gratiot County was no exception.

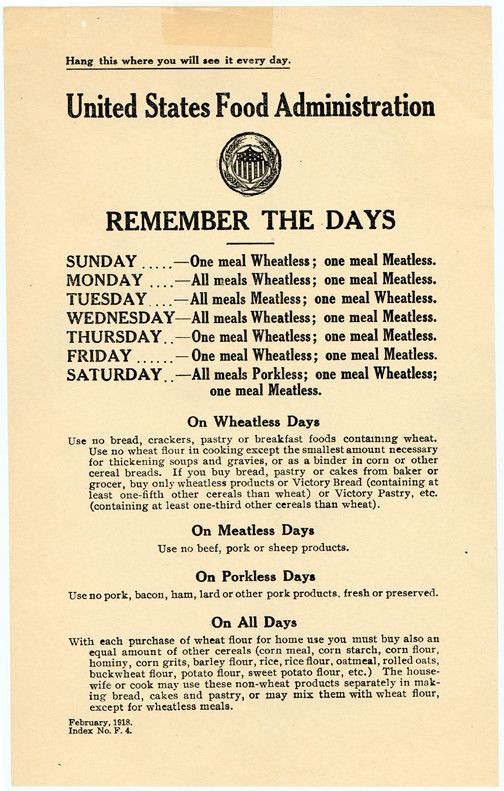

“We Won’t Win If We Waste” was the warning to housewives to do their part for voluntary rationing. Women were encouraged to reduce the use of wheat in their household by at least one third. They were told in newspapers, “Do your bit – small sacrifices now may save you from making greater ones later.” For example, dairy products were excellent substitutes, as well as eggs, macaroni, spaghetti, crackers, along with cornstarch and rice flour for puddings. Additionally, another form of patriotism involved the use of potato bread because Michigan had a surplus of potatoes. This substitute bread could be made with two cups of mashed potatoes for every cup of flour. These changes allowed a housewife to “beat the Kaiser at his own game” because “Bread and bullets will win battles for America.” By conserving the purchase of wheat flour, a woman might save enough money to buy another Thrift Stamp for the war effort. Other substitutes for wheat-based meals included barley mush, vegetable loaf, and carrot soufflé.

As Uncle Sam called more men for the war one of the groups included farmers and farmhands. There were those in Gratiot County who believed that these workers should be exempt from the draft because Gratiot County played an important part in providing food for the war effort. “A Farmer’s Daughter” sent a long letter to the Gratiot County Herald protesting the drafting of farmers’ sons. Both “city boys” and “country boys” were in high demand on farms in 1918 and many farmers depended on help from both groups. The draft boards were eventually told to try and delay calling all men engaged in actual farm work. A bulletin from the Adjutant General read, “Due to the scarcity of farm labor, the President directs that men engaged completely in agricultural work or farming…shall be given a deferred classification for the moment.”

Boys between the ages of 17 and 21 who could work on the farms in 1918 faced pressure to sign up for the Boys’ Working Reserve Program in the county. While school superintendents hoped that these boys would remain in school in order to graduate, many recognized the importance of their role in the war effort. At least one Michigan school district threatened students that if they did not work in the program then they would not be able to play football that fall. The state superintendent issued a statement that boys who entered the program were doing their community, state, and nation a great public service. The only criteria to enter the program in Gratiot County was that they were “physically qualified.” This hoped to add many boys to help out on farms in the county.

Other issues Gratiot farmers faced that month included the government’s decision to fix the prices of wheat, sugar, and beans. When the government failed to do the same for cotton in the South, county farmers felt that this was unfair and that cotton growers should also face restraints. Gratiot farmers were also urged to prepare for a nationwide tractor shortage. They were told that they should immediately place their orders for Ford tractors to be delivered starting April 1. It is unclear how many in the county could afford a tractor or how many purchased new ones.

The stories of Gratiot County men in the military continued to be read in the county newspapers. Arthur Wiseman and Clarence Frump from Ithaca both had going away parties given in their honor and both men received new wristwatches. Roland Crawford and Fred Crozier had dinners given in their honor in the evenings before they left for Fort Custer, both were Ithaca High School graduates. Roland was about to become a senior at the University of Michigan. Crozier was taking classes at Ferris Institute in Big Rapids and he was known for his work in pharmacy stores in Alma and Ithaca. Art Foote, the captain of the Alma College football team, was the seventh member of that team to leave when he enlisted in the medical corps. “Art” hoped to become a doctor and was well known and liked by many on the campus of Alma College.

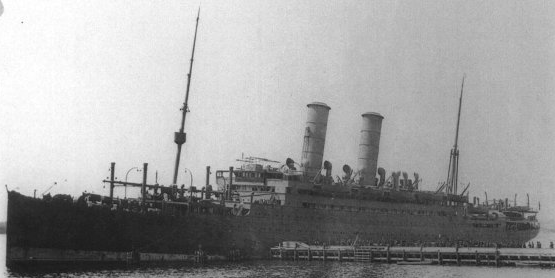

Other news about soldiers sounded more serious. One mother, Owen Courter of Elwell, was relieved when she got a telegram from her son who was in Europe. She was uncertain as to whether her son had been aboard the USS Tuscania, a transport ship that was torpedoed in early February off the coast of Ireland. By mid-March, she reported with great relief that her son, Glen, cabled home a simple message, “Arrived here safely.” Malon C. Briggs, who was in a camp in Middleton, Pennsylvania, wrote home to his family in Vestaburg detailing his unit’s battle against diphtheria and smallpox. The town had been quarantined and no one was allowed in or out. He and his men had received a player piano and a Victrola and they used these to pass the time. Walter H. Young, who was at a camp in Arizona, stated that a new YMCA building had been built and it allowed soldiers to write home. He also wrote that his group had just been issued new Colt .45 pistols. Whitford Unger wrote from England to tell his family that he was preparing for the move to France where “the biggest half of my battalion lie beneath the sod, and I will do the same to keep my dear old country free.” Bob Rayburn from Ithaca wrote from a camp in Newport, Virginia to tell his sister how a shell exploded inside of a three-inch gun, wounding thirty men and killing two. He added, “Several others were hurt severely. None of the Ithaca boys were near the gun so we did not get hurt.” Clarence M. Gruesbeck, who was in the 15th Field Artillery, was actually in France now and described the French people as being very sociable, although they did not work as fast as Americans. He was stationed in a small village where the house and barn were connected. Gruesbeck was living at one end of the building and animals were in the other. The cake that his family sent to him arrived and although it was dry, it was eaten “and we thought it was very good.” He still really wished for good American candy.

Call-ups for the draft went on. In Gratiot County, 50 men were called to appear for their physical examinations early in March. It was said that the government needed 95,000 men and 5,585 were to come from Michigan. Another 80 men were called, then the number reached 94. These men entered the service on March 29. Among the names who would never return to Gratiot County were George Washington Myers, Samuel Benjamin Derby, and William Lee Shippey. All would die during the war.

Different chapters of the Red Cross in Gratiot County performed their services to raise money and tried to increase their membership. Sergeant Major Russell of the Canadian Army, who had served at the Western Front for three years, came to the county and spoke at different churches. One meeting he held in Ithaca raised $370. Another at the Alma Presbyterian Church raised $250. Both places donated the proceeds to the Red Cross. Different events in Ithaca like thimble parties, dancing parties, and box socials also raised funds. Both of the movie theater owners in Ithaca and St. Louis showed movies and donated proceeds from a show to the Red Cross. A Red Cross drive in Alma hoped to raise the necessary $500 each month to do its part for the war. Solicitors went out into parts of the city to find new pledges of support. The money was needed because current funds did not cover the cost of shipping supplies to service areas. The Alma Chapter was very active and it asked people to help pledge something for this challenge. Even pledging only twenty-five cents showed that “This is one means of paying for the privilege of staying at home. It is your patriotic duty to give all that you can to one of the noblest services that the war presents.” The Alma Chapter also held a Firemen’s Ball and raised $108.44. Community singing programs continued as ways of showing support for the war and raising funds, however, once spring weather approached the programs were suspended.

The Red Cross chapter encouraged people in Alma to prepare to use any unused ground in the city for liberty gardens in the spring. Collecting clean, strong and durable clothing was needed to help reach a goal of sending 2100 tons to Belgium’s men women and children who were in need. The Alma Chapter asked readers, “Have you been to the Red Cross room this month?” A Free Reading Room with bulletins from the Committee on Public Information was available. Red Cross workers also were given new directions from Washington, D.C. concerning the official dress for those at the Alma Red Cross room. Each lady was expected to wear a white apron with sleeves to the wrist, along with a white coif. The instructor in charge wore a red coif with a white band. Any woman with 32 hours of work wore a Red Cross emblem on the left breast of her apron. The new dress regulations were to start April 1.

Also during that March, citizens were urged to show their individual patriotism. Over in Elwell, an announcement read, “It is believed here that it will aid the patriotic spirit if community singing of patriotic songs is taken up here the same as in many other places in the country. All that are interested are requested to be present this Sunday evening at the church. This means you!” The village of Sumner had similar meetings at the Christian Church. Service flags continued to spring up all over the county. The Ithaca Presbyterian Church presented, unveiled and dedicated its new flag with stars representing members from that congregation. The Booster Class of the Ithaca Baptist Church did the same thing on Sunday morning. Reverend Roberts fulfilled his role there as a “Minute Man” for the ceremony. The Minute Men in Gratiot County were individuals who gave short, four-minute speeches to show support for the war effort. The Committee on Public Information (CPI) prepared speeches for people to give at various times and places across the nation. Breckenridge High School also displayed its first Service Flag which had 34 stars on it. Businessman Carl Faunce in the same town had a service flag in his store’s window with three stars, each for a former employee who was in the service.

Raising money for the effort continued. People in Alma and Ithaca were encouraged to come and hear Gunner Depew, an American sailor who went off to the war in 1914 and fought for France against the Hun on both land and sea. The Third Liberty Loan Drive also started and the Alma Episcopal Church stepped up and bought $1,000 worth of bonds. Some county men in the service wrote letters home telling how they also had purchased bonds. Anyone in Gratiot County who could not buy a bond could buy Thrift Stamps. Many were urged to buy a stamp each day for only a quarter. Other things people could do to show support for the war involved watching high school cadets practice their drills at a basketball game between Alma and St. Louis. The Alma Order of the Eastern Star wanted to adopt a French Orphan and planned to raise money to provide for the child for one year. The C.A. Sawkins Piano Company in Alma asked for people to donate unused phonographs and records for soldiers at Fort Custer. Citizens were also asked to buy either a watch, razors, dining utensils or Masonic and Odd Fellows rings for soldiers who had gone off to war.

There also were warnings directed toward the disloyal or unpatriotic in Gratiot County. Penalties for hoarding were posted. Hoarders were warned of facing a $5000 fine and imprisonment for hoarding “in a quantity in excess of his reasonable requirements for use and consumption for himself and dependents for a reasonable time.” Also, the United States Intelligence Department asked for drawings, photographs, and descriptions of bridges, buildings, towns and communities in France, Belgium and Luxemburg that the Germans currently held. The government asked individuals to go through their collections and donate these items to the Intelligence Department, however, they would not be returned. Those who could help could leave their items at the Alma Record.

Finally, everyone was urged to prepare for the impending “Daylight Law” that would start April 1. All clocks were to be set ahead one hour so that places like factories in Alma could start work one hour earlier. Church service times did not change. It was what we called Daylight Savings Time.

Copyright 2018 James M. Goodspeed