Above: advertisements from the Gratiot County Herald and the Alma Record from September 1918.

Gratiot County residents continued to show their patriotism during September 1918 in support of the World War. Those who were deemed to be slow or resistant to support the war effort were quickly deemed “slackers.” The Alma Record ran an editorial column that month that warned readers that “We have no sympathy with such slackers, and we know that their neighbors have no sympathy with them. Shame should be their part if nothing more…No matter what the request of the government at this time, we should attempt to hold to it.” What brought about comments like this? One incident involved L.G. Hull, a farmer in Hamilton Township, who had his barn and house painted yellow with the word “Slacker” on them. It was said that Hull made “slighting” remarks about the government, that he would not buy Liberty Bonds or War Savings Stamps, and that he refused to contribute to the Red Cross. It was noted that the paint could be read from quite a distance from Hull’s property.

In some cases, people found themselves being looked down upon because they refused to conserve gasoline by not driving on Sundays. In Alma, license plate numbers were written down and the Alma Record threatened to publish the names of those who did not observe fuel conservation. In another instance, Lionel Griffey of St. Louis was arrested in early September because he claimed to be too old to be drafted. Griffey claimed to be 30 years old, but his mother verified that he was only 20. However, for some unknown reason, Griffey was allowed to leave St. Louis with a carnival that he was working for.

Businesses like the Republic Truck Company showed their patriotism by flying a company service flag which added a star for each employee who left for the war. Gold Stars represented former employees, like George Washington Myers and Howard Wolverton, who died in the war. A special prayer meeting about the war in France was held at the Ithaca Methodist Church late in the month. The public was invited.

A War Savings Stamp sales drive started September 10 and it was expected that every citizen in Alma would buy stamps. The city already had raised a total of $42,000 with a goal of over $400,000. Ladies at St. Mary’s Catholic Church invested over $100 in stamps. The St. Louis Presbyterian Church held a meeting on how to instruct people who volunteered to sell bonds. Down at Middleton, students in the Intermediate Room said that they had $600 worth of Liberty bonds and $290 worth of stamps, but they still hoped to purchase more. This was all done by a group of 42 students (30 boys and 12 girls). The Alma Fire Department used $350 that it had in its pension fund and decided to purchase Liberty Loans with it. The fire department hoped to invest a total of $1350 in bonds. In order to get people to buy Liberty Bonds, plans were being made to bring Senator Vandenburg from Grand Rapids to make to visit Alma for a Liberty Bond program. The Jackie Band would play and the National Guard would be present. People were asked to supply automobile rides to transport the band to places like Alma, St. Louis and Ithaca. Gratiot County had been told that this Fourth Liberty Loan’s goal was to raise $900,000.00 and 100 volunteers from across the county were expected to be involved in the drive. The Alma Record told readers to “Have it all figured out by Saturday just how much you can afford to lend, then subscribe for double that amount. Pinch yourself to pay for the other half (of the pledge).”

The county continued to urge people to ration and conserve resources. On a gasless day in Alma, ninety percent of automobile owners observed the day by not driving. However, 350 odd drivers who did drive around the city the following Sunday faced the National Guard Company 87 which was out at various points looking for drivers and then recording their license plate numbers. Someone in a newspaper suggested that cars should be ticketed and the money given to the Alma Red Cross. A week after this, a letter arrived in Breckenridge from the Federal Fuel Administrator that told people that if they needed to drive to church on Sunday, then they should do so and they should not be deemed unpatriotic. This was in response to someone who had gone around town painting the term “slacker” on cars that were in church parking lots. The Secretary closed his letter by stating, “It is all right to apply both food and fuel rules strictly, but it is not right to call any person a ‘Slacker’ without the most careful investigation.” Over in St. Louis on Sunday it was noted that no automobiles were seen on the streets, no gas was sold and all garages were closed.

The C.J. Maier and Company clothing store in Alma also ran an advertisement stating that “You can save or waste in buying clothes.” Even though the store sold clothing it appeared patriotic by telling people “Maybe you can save money by not buying any (clothes); you may have clothes enough. If you need to buy, save by getting the best clothes possible…” Farmers were being encouraged to invest more crops in “Liberty acreage” by planting even more winter wheat for the war effort. Children in Alma who belonged to the city’s canning clubs put on a display late in the month at the high school. They were asked to show a basket which contained foods that they had put up from their summer’s garden. Starting in September, the “fifty-fifty requirement” was abandoned and housewives were told by the County Food Administrator that they could buy standard flour at the proportion of one pound of substitute mix to four pounds of wheat flour. There continued to be a call for boys to be allowed to miss school in order that they could help on area farms with the harvest. Half of the farm help from the previous year was gone due to Gratiot men going off to war. A notice out in Vestaburg still asked women to save fruit pits and shells from various nuts for gas masks.

Among the most devoted and patriotic workers in the county continued to be those with the Red Cross. Out in New Haven Township, the Red Cross held a township hall social and raised $80 when a Crystal man won a quilt raffle. In Ithaca, the Red Cross there opened their rooms on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. Help was needed in the sewing room and ladies were asked to loan their sewing machines if they were not using them. Five little girls paraded around Ithaca carrying a flag and asked for donations. They raised $4.40. In Alma, metal and paper drives continued at the Washington School. A Mrs. M.M.Barker from the city donated money to the Red Cross from the thirty table boarders that she had at her house. Young women were encouraged to join work for drug laboratories as hospital nurses. Families in Alma of soldiers and sailors were encouraged to ask the Red Cross for help in writing letters to their men overseas. Also, these family members could count on the Red Cross to be there in Alma to help if they needed “advice, assistance or management of their affairs.” The Alma Chapter asked the city for help in its quest to support the National Red Cross in raising fifty tons of used or surplus clothing for those in need in Belgium. Government leaders also continued to ask housewives to conserve use of butter and milk. Even though the Alma chapter always asked for help, one Thursday evening saw 64 ladies show up to work at the tables. Dan Reed, from Flint and a National Red Cross worker, came to the city and gave a war lecture about his experiences of being on the battlefields in France and Belgium to over 200 people at the Republic Truck Factory cafeteria.

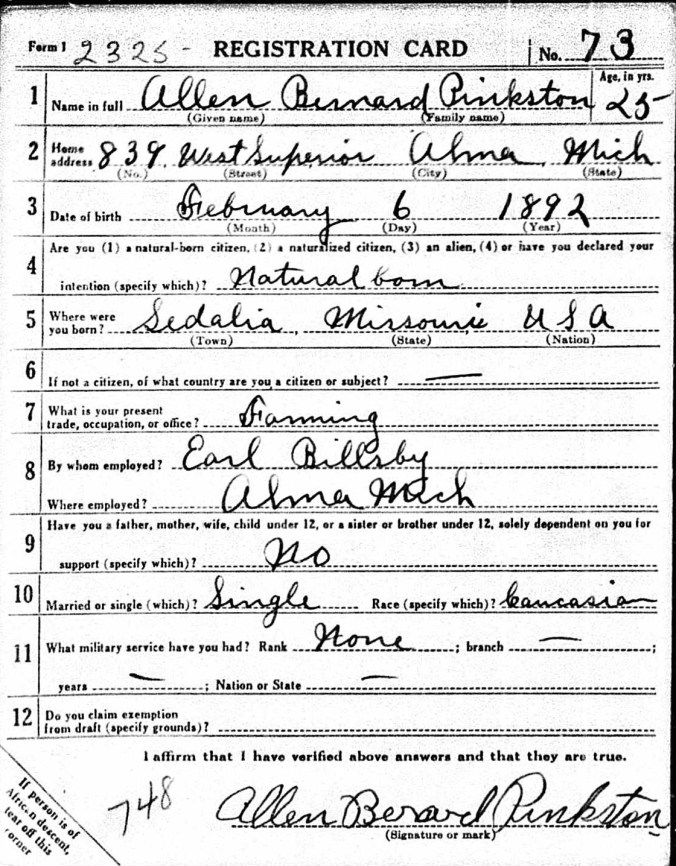

When it came to military service, Gratiot County men were still being drafted that fall. Those men who had turned age 21 since June 5, 1918, had to register with the local draft board. The government wanted to have a fighting force of 13,000,000 men and then called for a new registration of men between the ages of 31 to 45 years of age. Men were still expected to fill out registration cards and they were given a deadline of September 12 to have them turned in. On the day of the deadline, patriotic celebrations were held throughout the county. In Ithaca, one was planned for the courthouse yard and all businesses in Ithaca were closed that afternoon for two hours. A band played, school children read recitations, speeches were given by community members and the county’s National Guard performed a drill. The service ended with the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Almost 4,000 men managed to register on that day and it was said that since the start of the war, 6,631 men from Gratiot County between the ages of 18 and 46 had done so. At this registration boys aged 18 were encouraged to go to college where they could enter military training there. Those who entered the Students’ Army Training Corps were given tuition, clothing, lodging, board and $30 pay per month. The incoming group of SATC boys was so great at Alma College that the college planned on turning the museum into a barracks because Pioneer Hall would not hold all of them. The school was also delayed that month until October 2 because of the rush of incoming applications. Some of the boys would end up being turned away because the new barracks could only hold 150 members.

There also continued to be stories of the men who were engaged in fighting the war. George Karras, who managed the Paris Café in Alma, went off to join his two brothers who were in the service. Also in Alma, registered men were encouraged to have a photograph take before they went off to war. Two African American men, Leroy Porter and Dayton Alton, were being sent to Camp Custer on September 27 to fulfill the recent quota for African American soldiers. Floyd Thomas, stationed in France sent a German steel helmet home to his mother in Ithaca. Private Guy Gongwer wrote to his parents in Alma that he claimed that German women were being forced to fight at the front, along with German soldiers. Gongwer stated that some of these women were found chained to their guns. This same Private Gongwer would receive a citation from General Pershing that would lead to him being awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. Gongwer was awarded the medal for his efforts to treat the wounded in the Argonne while his unit was under heavy fire. Private E.E. Down of the 338th Infantry wrote home that he had arrived safely in England. He found the YMCA there to be of great help with morale and with writing letters home.

Sergeant D.C. Parrish wrote to his friend, C.M.Brown in Ithaca, about how beautiful French women were because “they have the most beautiful eyes. As a general rule the girls are very pretty, so for one fond of beauty, there is always some pleasing sight upon which to feast one’s eyes.” Private Alva Cook described in a short letter what combat was like for him. After charging up a hill and being then being pinned to it because of heavy fire, his unit chased the Germans for sixteen miles. Walter H. Young wrote about why he treasured his own helmet as he had put it on just before his group encountered a shelling from the Germans. He added, “It was all that saved my life.” Elmer Down of North Star thought it would not be long before he and another North Star boy would be drinking beer in Berlin – if the war continued to go as it had in the last month. Robert Shuttleworth wrote that he had seen the worst of war: dead horses, men, guns, ammunition – all after the battle. He was so busy that he had only washed twice since arriving in France. He also wrote about the American soldiers’ fascination for souvenirs when it came to piles of German helmets, emblems and he wished that he could take pictures of the destruction of what he saw.

Finally, in September there were clues and notes about a new movement in Gratiot County that was taking place amidst a time of war. This happened to be what was called women’s suffrage and their right to vote. On September 5, a big mass meeting was held at the Alma High School auditorium. The President of Central Michigan Normal School, E.C. Warriner, was the main speaker. Two weeks later, another mass meeting was held at the home of Mrs. F.M. Harrington in Ithaca. The women and supporters were moving to organize their campaign for the proposed amendment to the Michigan constitution that fall. Forty women attended the Ithaca meeting, including nineteen township chairmen. It was said that several Alma merchants were going to give their advertising space to the suffrage movement in the upcoming issue of the Alma Record.

And that was September 1918 in Gratiot County during the World War.

Copyright 2018 James M Goodspeed