Above: Advertisements from December 1918 issues of the Alma Record

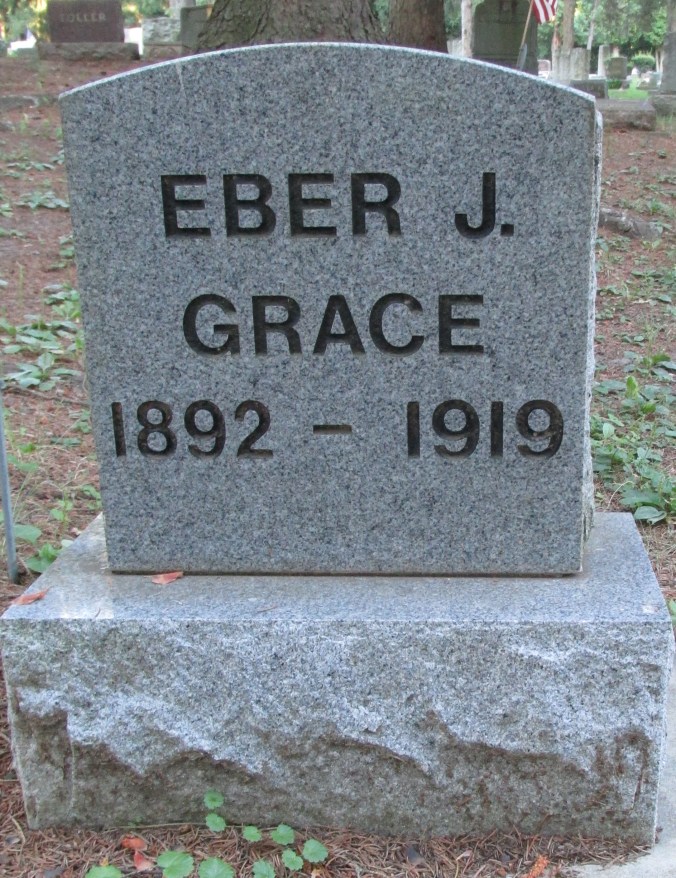

Note: This is the last in a series of articles about Gratiot County during World War I. This series chronicled the people, events, and news that took place just before the United States declared war in April 1917 and ends with Armistice.

It was December 1918. Gratiot County had been a part of the World War for almost 20 months, and the war had finally ended. The county had been ravaged by the terrible Influenza Epidemic starting earlier in the Fall. In the meantime, the war wound down, and an Armistice came on November 11. The county celebrated America’s victory overseas and now the nation – and Gratiot County – started to wind down and turn to postwar society. Christmas was coming in Gratiot County, and people began to think of things other than war. Still, there were plenty of reminders of what this war had cost.

Some of the last published letters from soldiers appeared in the newspapers. While a few appeared sporadically in early 1919, this was last month that they received such extensive publication.

Bradley Stone, 141st Aero Squadron, wrote to a friend in Ithaca about seeing the damaged and scarred French countryside. A letter dated in October told how he found a downed Hun plane and what it was like to watch air battles. On one day he witnessed two German pilots land near him, thinking that they were safely inside the German lines. Upon quickly discovering their error “…up went their hands and down went their spirits.” One German was well dressed and spoke good English. The other, more shabbily attired, “looked like a bum.” Regardless, Stone’s officers offered cigarettes and asked them questions concerning the German lines. Stone also was amazed at how much material was laying on the ground as the Germans retreated. “A person can pick up most anything in the way of equipment – guns, ammunition, scattered everywhere. The country is quite hilly and cut all to pieces.” Upon looking inside one French home, Stone could see the interior of a bedroom, complete with pictures still on the wall and with a washstand standing against a wall. The problem was that the entire front wall of the home had been blown away.

Walter Young wrote that he was already somewhere in Germany with the Army, twenty-five miles from the Rhine River. Mike Scott had been stationed aboard the USS Montana and was now in Germany. He thought most German people were friendly and some spoke English. He even met some Germans who had lived in the United States before the war. Corporal Percy Strouse of the 47th Infantry could not wait to return to Gratiot County and wrote to friends, “I am coming (home) to eat pie, cake and ice cream if you will make it for me. I have not seen much of either since I came across and no ice cream at all, so you see it will take a whole lot to fill me up.”

Private John Spencer of the 338th Infantry had made it to France; however, his first stop was in Liverpool, England. While there, he visited the YMCA hut and found Miss Agnes Yutzey of Ithaca, who was a friend of Spencer’s mother. Private R.M. Trinkham wrote to his father in Alma about serving in France with a car repair department for about one month outside of Marcy, France. While there he saw American supplies going toward the front at the rate of 25 trains a day, a record for his unit. Private Ira Williams of the 338th Infantry saw plenty of enemy Germans, “They have a lot of German prisoners here. They are a hard-working bunch.” Harold Redman reminisced about his summer trip over to England via a Transport ship. There were fifteen transport ships, two battleships, fifteen sub chasers and airplanes in this group. Redman remembered sleeping with his life preserver on at night in case the ship encountered attacks from German U-boats. James Carter of Alma wrote that he witnessed the surrender of the German fleet while he served aboard the USS Wyoming.

Others had more severe problems. Elwyn Follett had to be invalided home from France because he was a victim of a German gas attack and almost lost the use of one eye. He had been in a hospital for over one month. Private Walter Wilhelm was recovering from wounds. They were looking better – he had one in his foot, with minor injuries to a leg and his hand. “I have quit dressing all (of them) except my foot. I do not think it will be of much account, but still, it may come all right. I have a fine doctor.” He did have several aching teeth that needed to be pulled and he was soon to see a dentist. Private Earl Christy had been sick for ten days with influenza. He and his friend had recovered, and Christy was again working near the flying fields in his area. Christy sent a picture home and hoped that the Gratiot County Herald would print it. Sergeant Ted Kress wrote that he expected to be home in Ithaca very soon and planned on celebrating Christmas with the Barden family.

In many cases, people in Gratiot County learned several months later that their son or husband had died or that they were considered missing. Part of the problem was that of over 262,000 announced casualties, only 105,000 had been reported so far by the government. Both the public and Congress pressed the Secretary of War about the rate of notification and the fact that families wanted to know what was going on with missing men.

Oscar Narrance, an Alma College football star, was listed as missing in action. Lieutenant Charles Robinson, a former Alma College athlete, was recorded for the first time on casualty lists from the Army. Private D.R. Simmons was also listed as wounded, but not to what extent.

Private Thomas Stitt sent word that he was in a hospital and recovering from shell shock. Carl Titus got word home that he was with the Army of Occupation in Germany. His family had not heard from him in several months. Lieutenant Edward H. Wyatt had been cited for bravery after being wounded in September while defending his platoon’s position which was under attack for an hour.

When soldiers began arriving home, they frequently made the news. Kenneth “Dutch” Hoyt and James Barry of Alma made it home after seeing action in France. As others made their way back over the next few weeks and months, the newspapers mentioned their returns.

The Red Cross attempted to keep its work going and held meetings and events in different places in the county. At Pompeii, a Red Cross Lecture Cross featured Dr. Elwood T. Bailey, a welfare worker who just arrived from his work in England, Italy, and France. During his service, Bailey had encountered thousands of American soldiers. Although he talked for almost an hour and a half, his audience wanted to hear more of his address, “From Transport to Trench.” Attendance was small, however, because of the recent fear of contracting flu. The Alma Red Cross kept busy setting up booths in the post office, both banks and the drug stores in Alma to recruit new members, instead of conducting house to house recruiting drives. The chapter hoped to produce ten serge skirts for its quota in December. Also, unused gauze was sold to the public for nine cents a yard. Mothers and wives of deceased soldiers could obtain a “mourning brassard” free of charge. Made of soft black broadcloth, the brassard had to be worn on the left sleeve between the elbow and shoulder. The women also spent nearly $25 at the Republic Restaurant for doughnuts for local soldiers. Recruitment for new members in Ithaca was also a goal there, even though that chapter boasted 600 members. In all events, only current members could wear the Red Cross Badge, which signified that they were in good standing with the local chapter. The Ashley Chapter kept its rooms open and planned to work on refugee garments.

Even though the war had been over for several weeks, there were still things happening with “war work.” Alonzo Beshgetoor had been working at the United States Chemical Service in Cleveland, Ohio as one of one hundred chemists working on the deadliest gas yet created. Methyl was reported to be 72 times more poisonous than mustard gas. The Cleveland plant where Beshgetoor worked was producing the gas at the rate of twenty tons per day, enough to kill 650,000 men. After months and months of food rationing and conservation, the United States Food Administration published articles of how “Food Won the War.” Still, the United States was sending 200,000 tons of food to Europe to help the people of France, Belgium, and Austria.

Alma College was demobilizing the SATC program starting in early December. A luncheon at Wright Hall and a dance at the high school gymnasium marked its conclusion. President Crook stated that the college museum would no longer exist as a dormitory. The county also learned about the upcoming Fifth Liberty Loan Drive, which would start in the spring. The Michigan Chapter of the United States Boys Working Reserve asked Gratiot County to prepare to recruit boys to work on county farms in 1919 in anticipation of the need for more farm labor. It would be the third summer in a row that the program planned to operate. Earlier in December, Alma High School girls pledged more than $500 for the United War Work Campaign. Most of the girls would raise the money by doing work after school. Merchants and banks began to publish notices that Liberty Bonds would be accepted as payment on things like a new suit of clothes, personal loans or purchases of automobiles. These would appear with regularity over the next few years.

Finally, there were stories about daily life in Gratiot County that December. The Idlehour and Liberty Theatres planned to reopen in December. The Idlehour had a new motor-generator installed, and Paramount pictures would run five days a week. What the advertisement did not tell readers was that businesses were waiting to reopen due to the Influenza Epidemic. Lefty Pipp, star first baseman of the New York Americans visited Alma at the end of the month. A North Star man, “one of the meanest “ in the county, had been located and arrested for beating his pregnant wife. She gave birth while he was in jail. Walter Todd and his family prepared from Lansing to Middleton to operate the bakery there. George Wheeler, a young Alma resident, was arrested for sending obscene matter through the United States mail. Alma stores announced that they would remain open evenings starting December 9 and do so until Christmas.

So, that was December 1919, the last month of the World War and Gratiot County.

Copyright 2018 James M Goodspeed