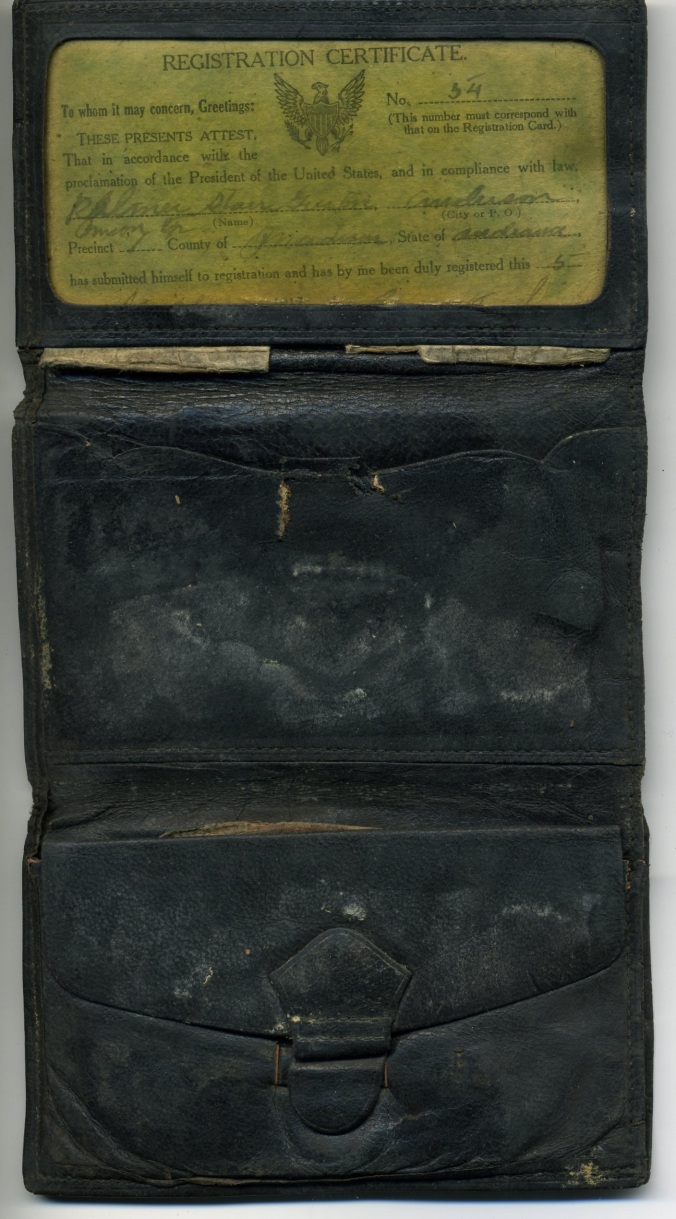

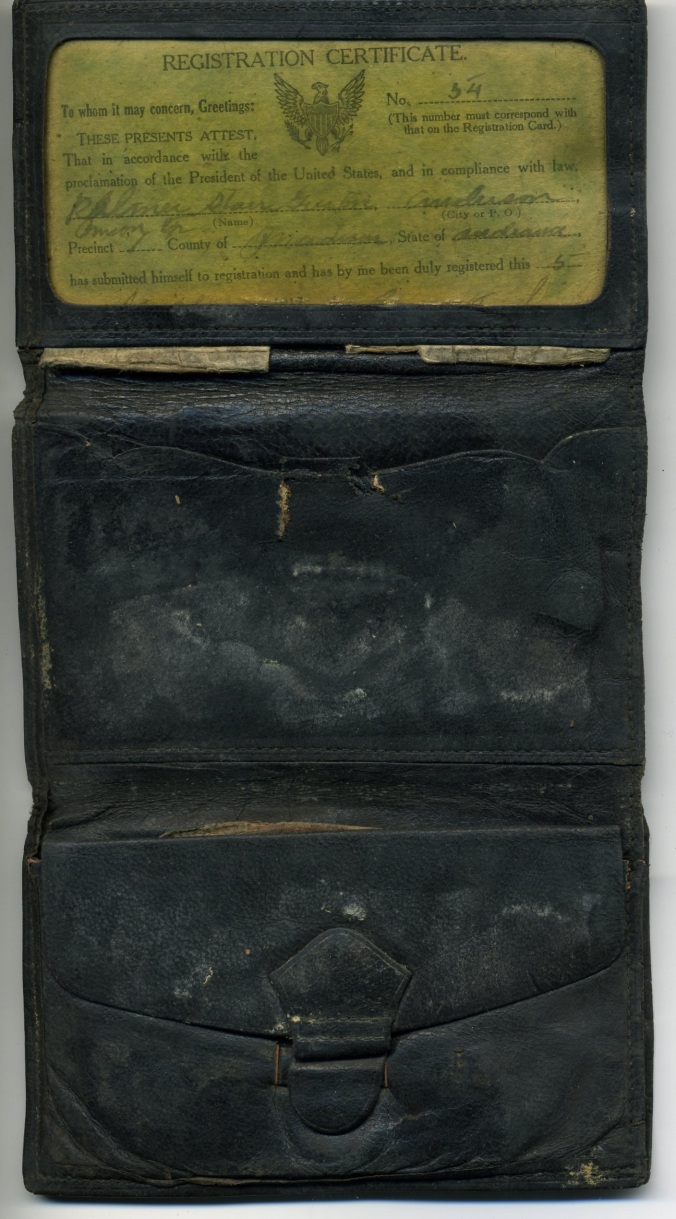

Above: Photograph of Palmer Starr Gustin; Gustin’s wallet; Jim Goodspeed’s World Geography class at Fulton High School, Fall 2005 with the effects of Palmer Gustin; Gustin’s induction paper; Gustin’s grave in Indiana.

The papers, wallet and American Flag did not appear to draw any interest. When I first saw the auction lot on eBay I was interested in the contents of the lot, and even more, intrigued that no one seemed to want it. There was only a short time left on the auction and the contents belonging to a World War I veteran from Anderson, Indiana just sat there.

It was early 2005, the internet was buzzing, and the United States had not yet suffered its greatest recession since World War II. Items pertaining to American military history could be found on the internet and those from the World War I era, while prevalent, often did not draw that much attention. It was as if World War I was a forgotten war – and this group of items in this sale was available.

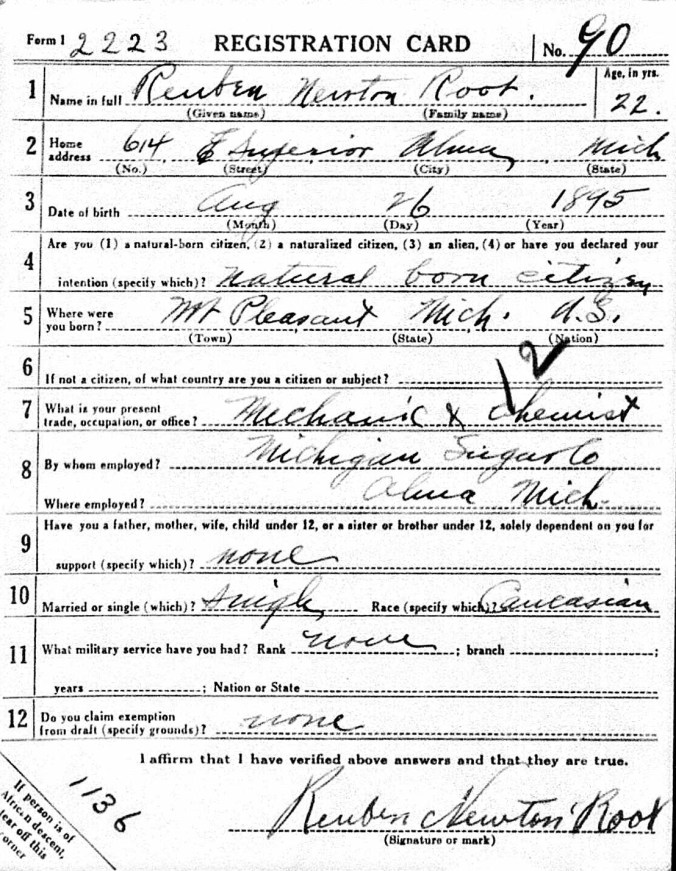

After I won the contents of the lot and it had been delivered to my room at Fulton High School in Middleton, Michigan I wondered just what the story was behind a soldier named Private Palmer Starr Gustin. All of the contents were the remains of an estate sale and contained a slightly mildewed American flag from 1918, a billfold, a Red Cross receipt for a $1 donation, a photograph of a girl, and a bank book. Other, more interesting items, included Gustin’s registration card, conscription letter, General Orders, names of other soldiers on a notepad, a poem about Kaiser Wilhelm and his draft board classification card. There was also a very large, oval-shaped, “fish eye” type of photograph of a soldier that had since been removed from a frame. There was also a collection of condolence cards; one was signed “War Mothers.”

Since I tended to be a part-time History teacher, and because I seldom got the opportunity to teach American history, I had to be creative with ways to get history into the classes that I taught. During the fall 2005 semester, I had been assigned a World Geography class. I decided that I would do the unusual: let my small group of Geography students do the detective work on the internet to see what they could find out about this collection of World War I items and just who this Palmer Gustin really was. I could argue that I was teaching the geographic theme of “movement.” Actually, I just held my breath, did not tell my administrator what we were doing on Fridays and let the students learn something about history.

The internet in 2005 did not have all of the search engines and sites that exist today. Many museums and archives were just then coming online with access to their collections and many had just started to digitize some of their holdings. Still, I was surprised at what my students were able to find.

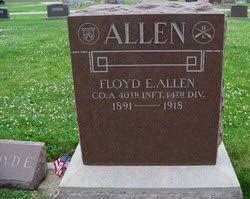

It turned out that Private Gustin was the son of John and Nellie Mae Gustin and the family had lived in central Indiana for quite some time. Born in 1898, Palmer was the eldest son of five children. His only brother, Arthur, died in 2004 at the age of 97. It was also discovered that Palmer appeared before the local draft board in Madison County in August 1918 and he was sent to Camp Sheridan in Alabama. There he became a part of Company C, 67th Infantry. All of this happened after he had been rejected from the Army and Navy in 1917 and then was accepted for Selective Service in 1918. It was then that the class found out that something very bad had happened to Palmer Gustin.

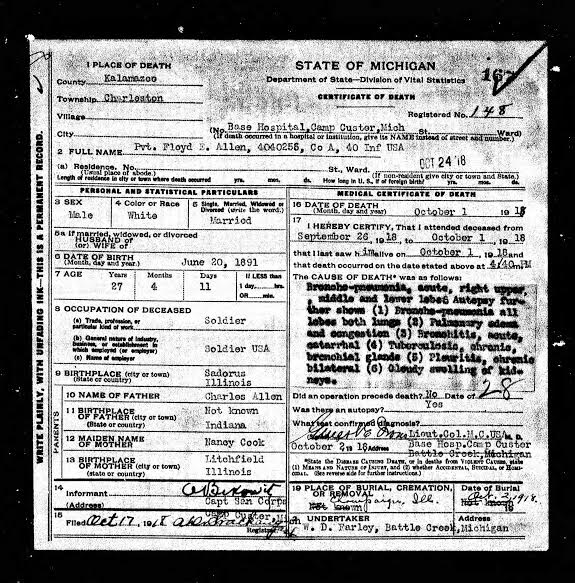

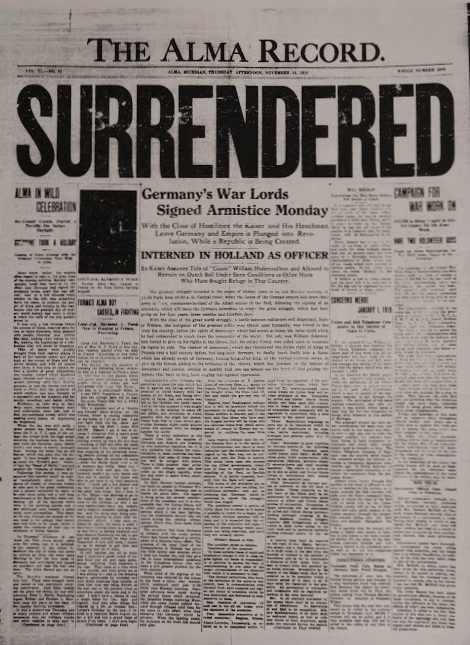

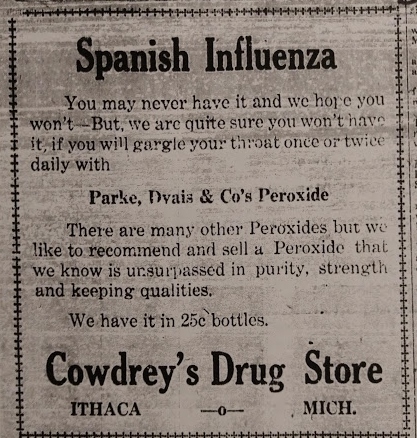

Gustin had been at Camp Sheridan for a short time in the fall of 1918 (possibly eight weeks) when the Influenza Epidemic hit the camp. Camp Sheridan was not the only camp to experience the epidemic, military cantonments (camps) across the United States had been invaded by the virus by September 1918 at the latest. Some encountered it earlier that spring. Soldiers quickly became sick with influenza, were incapacitated and then frequently suffered pneumonia, which killed them. Palmer Gustin contracted influenza and died on October 24. A week before Palmer died, a total of 2,367 cases of influenza were reported in the camp. This young man from Indiana, age 22, was one of those who was taken in the epidemic.

After my class tried to make sense of the puzzle that they had been given, the question was asked, “What should be done with the remaining effects of Palmer Gustin?” The next assignment was to find out if any family members were still alive and if they could tell us anything else about this soldier. We were lucky and we discovered that there was a niece still living in the Anderson, Indiana area. Of course, Mr. Goodspeed was nominated to try and make the initial contact. I did and I found Paula Bronnenberg, who was very interested in her great uncle’s belongings and she wanted to know why a bunch of students from another state found them. Mrs. Bronnenberg helped to fill in some of the pieces of her uncle’s life. Paula lived in the same farmhouse that Palmer Gustin had been born and lived in. She knew of his death in the flu epidemic and she also knew who the girl was in one of the pictures that I described: it was her grandmother, Mattie Palmer. Mattie’s first name was on the back of the photograph.

Bronnenberg also explained that there had been an estate sale in the family and that she had failed to obtain Great Uncle Palmer Gustin’s military items. We decided as a class that these things belonged in Indiana and we shipped them back to her. I took pictures and made copies of the items before we returned them and the file disappeared into my crowded filing system until I remembered having it some two years ago. At the time, I was starting to investigate Gratiot County in the Great War and this thing called the Influenza Epidemic. As a teacher, my small group of Geography students had been introduced to the deadly event in history known as the Influenza Epidemic of 1918. I knew a little about this pandemic, but what really happened in Gratiot County?

This was the next adventure.

Next time, Part II: The Background of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic

Copyright 2018 James M Goodspeed